Authored by: Diksha Pandey

Today, more than 1.2 billion Indians have a unique digital identity [1], and along with that, access to a basic savings account as well as the choice to conduct payments online using the simplest, low-cost mobile phones. Aadhaar has been the foundation, in the truest meaning of the word, of the bridge built to reach the rural and urban poor population of our country through the expansion of the formal financial infrastructure, which aids in providing them with both governmental and non-governmental welfare services.

By facilitating Direct Benefits Transfer (DBT, hereafter) to the poorest households, Aadhaar has saved the government INR 900 billion [2] by reducing corruption, funds diversions, as well as fund leakages. However, at the same time, technical and data point errors in seeding of Aadhaar have acted as barriers in availing welfare services, jeopardising many lives. Thus, an expansive coverage alone cannot be an exclusive measure of Aadhaar’s success.

Apprehensions that the Aadhaar project will create a framework within which the government operates as a Big Brother have been around since its launch in 2009. Several data security and privacy concerns have also been raised, prompting the Supreme Court to intervene and regulate the future course of Aadhaar. In this context, the debate around Aadhaar becomes complicated. This paper explores how the usage of Aadhaar in tackling the extent of financial exclusion in India can then be balanced with the need to protect personal data rights.

AADHAAR AND FINANCIAL INCLUSION

For India to remain on a high growth trajectory, the participation of all sections of society in its formal banking sector is crucial. Jan Dhan, Aadhaar and Mobile, also known as the JAM Trinity, has been regarded as a social revolution [3] [4], establishing equality and inclusion as the focal points of good governance. Around a billion bank accounts and mobile phones have been linked to Aadhaar in the last seven years, with financial transactions linked to Aadhaar amounting to over 12 billion USD [5].

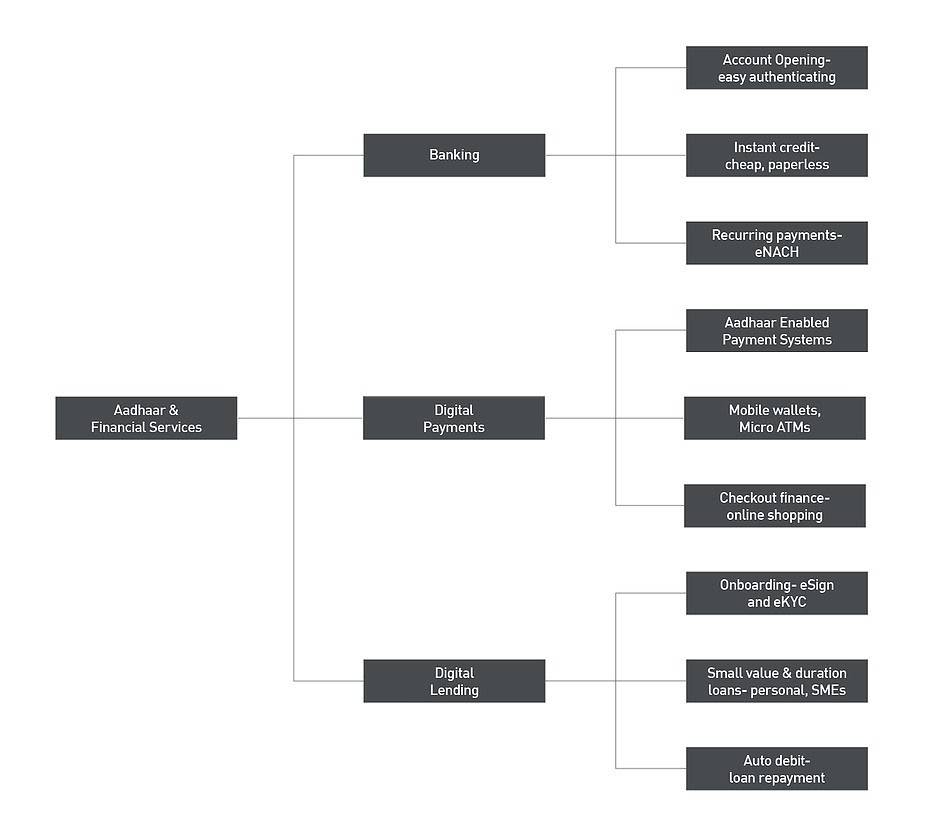

E-signature linked to Aadhaar has quickly become the single source of authentication while operating several banking services, such as digital wallets. For companies across sectors and new technology start-ups, which offer financial services based upon Aadhaar verification [Chart 1], the process of consumer on-boarding has undergone radical changes; consumers can fill up forms in mere seconds, digitally sign documents through Aadhaar, and authenticate themselves through biometrics at a minimal cost, drastically reducing the number of people who drop out in the middle of the registration process.

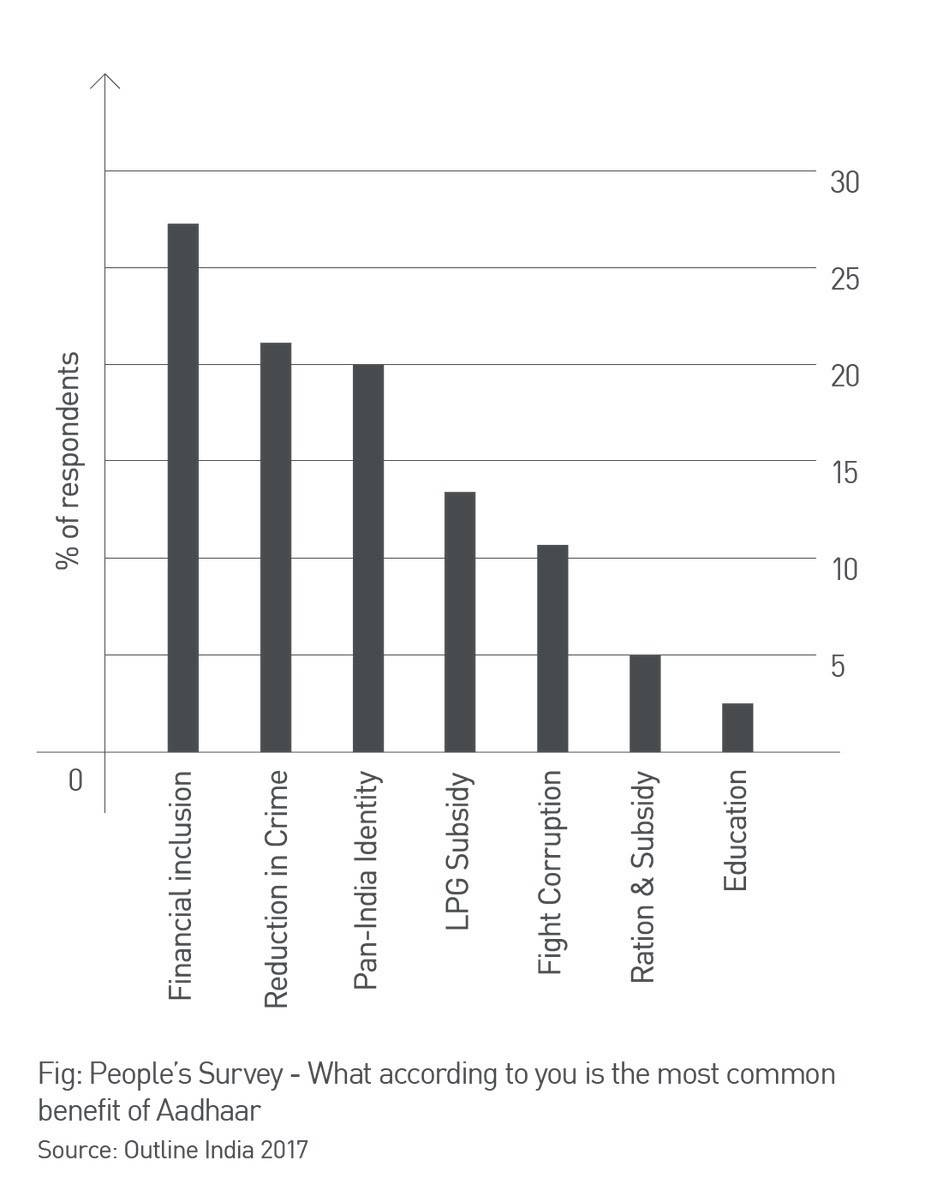

The operational model of Aadhaar has also ensured the sustained usage of bank accounts. Since low or zero balance is the most common reason behind account dormancy, DBT encourages people to actively operate their accounts. It is not surprising, then, that financial inclusion has been the most widely perceived benefit of the Aadhaar program [Chart 2].

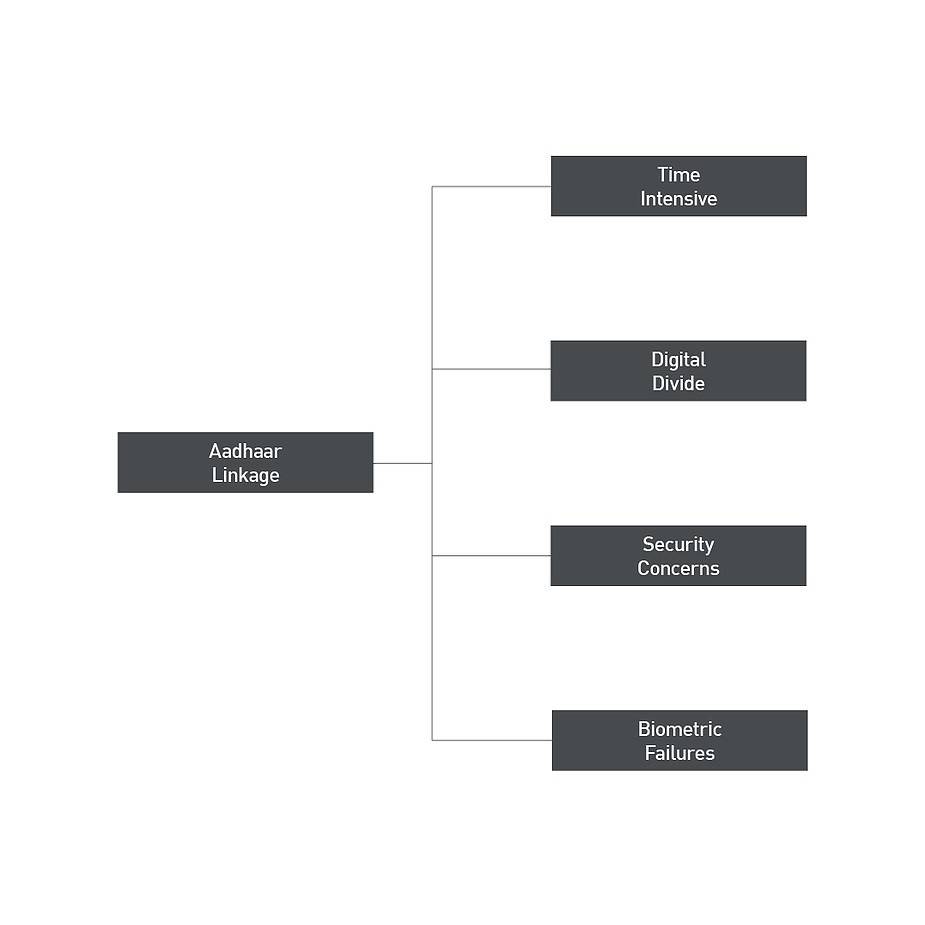

However, the entry of Aadhaar in the financial services industry is multi-dimensional. It was with the intention of building economies of scale, and ensuring equal access to the country’s banking infrastructure, that linking Aadhaar cards to personal bank accounts was made mandatory. While feedback on this move outlines multiple hitches [Chart 3] and varies across different social strata, it is pertinent to explore the discourse around data privacy and usage within Aadhaar.

Over the last seven years, several parties have flagged concerns with respect to turning over their biometric data, and the extent to which it can be used by agencies without their consent, thereby violating their privacy. Lack of basic information security and two-factor authentication has made the harvesting and duplication of Aadhaar numbers an artless task. Open, unsecured directories continue to be used to store sensitive data on many government websites that interact with Aadhaar. Many third party companies that banks operate with, are guilty of illegal exposure of Aadhaar database. Earlier this year, through the website of a leading LPG connections provider, Aadhaar data of over 6 million subscribers was leaked [6]. Identity theft, and SIM and banking frauds are now easier to commit, as indicated by their increased frequency. Integrating Aadhaar data with sensitive information regarding parameters such as caste, religion, and employment details, including the salary earned by an individual, opens them up to the risks of discrimination based exclusion.

The use of Aadhaar calls into question several other data rights as well, such as data ownership, portability and exchange of data, interpretability of personal data sets, and an individual’s right to be forgotten [7]. Taking stock of the above, it is possible that the Aadhaar linkage exercise might have snowballed into a system with data fallouts that are hard to regulate.

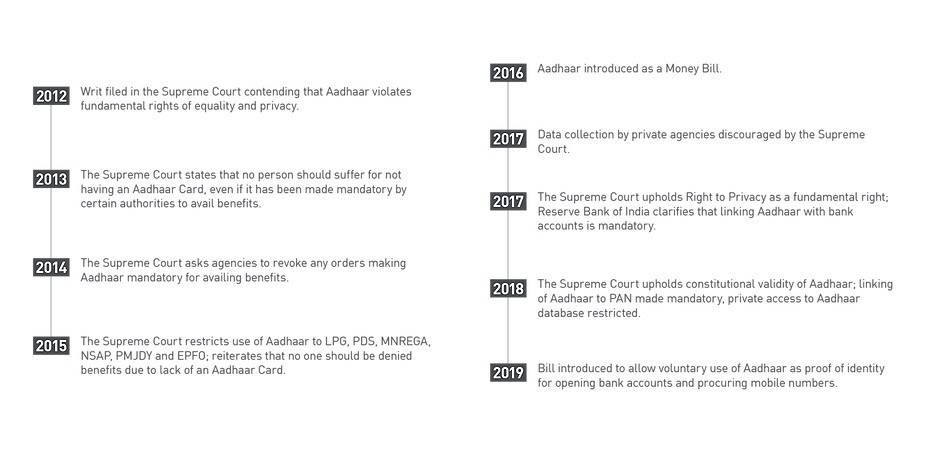

THE SUPREME COURT CONUNDRUM

Aiming to provide a sense of relief, and bring clarity to the legal framework within which Aadhaar operates, the Supreme Court passed a landmark judgement in September 2018 [8]. By this ruling, private entities’ access to the Aadhaar database for purposes of identity authentication was cut off and commercial exploitation of personal data was deemed unconstitutional. The judgement not only disrupted the services being offered by several FinTech companies, it cast a question mark on the mission status of turning Aadhaar into an identity infrastructure for the whole country.

Exploring what the judgement means in terms of its impact on businesses, operational costs might increase by almost 100% while making a switch back to physical modes of verification [9]. The processing time of paper-oriented processes will go back to taking 7 to 14 business days, as opposed to mere minutes.

Senior lawyers have also pointed towards several issues with the judgement. For example, even if a customer voluntarily wants to use their Aadhaar identity to complete the process of e-KYC, platforms run by private businesses cannot accept it. It is also unclear whether or not the government can promulgate a specific law to enable private parties to use Aadhaar which can survive judicial scrutiny.

Earlier this year, the President approved the promulgation of an ordinance allowing the voluntary use of Aadhaar by private entities, countering the Supreme Court ruling. The Aadhaar Act was also amended by the government to allow voluntary use of Aadhaar by customers to establish their identity. The amendments have been deemed necessary as many welfare schemes rely on a private-public partnership to reach the beneficiaries, rendering private access to Aadhaar data indispensable. Simultaneously, many are disappointed, and have interpreted the above move as the government’s disregard for the court’s decision upholding personal data rights, as well as the right to privacy.

THE WAY FORWARD

The demand for transparency and greater control over personal data is justified, and the concerns around data security are not driven by paranoia alone, given cases of recurring data breaches across the world. Nonetheless, the discourse surrounding Aadhaar needs to be more nuanced than a clash between those prioritising the economic aspirations of the masses, and those for whom data privacy takes precedence.

There is a need to introspect India’s policy approach to Aadhaar. There is a possibility that making Aadhaar linkage optional, and giving people an option to deactivate their Aadhaar, might encourage more participation in the Aadhaar project. The United States government, for instance, ran a pension scheme where in the workers were automatically enrolled. It was observed, however, that only when the workers were presented with the right to opt out, that the participation rates doubled. [10]

Subsequently, India will need to ensure that institutional protection, while necessary, does not become a roadblock for innovation and instead ensures sustainability in adoption of new technologies. Meanwhile, it might be time to explore alternatives to Aadhaar e-KYC and biometric authentication for digital delivery of services, one which can fare as well given the country’s high rate of illiteracy and limited internet connectivity, among other last-mile delivery hurdles, in rural areas.

How the Unique Identity Authority of India, which operates and regulates Aadhaar, satisfies concerns of data privacy and security while harmonising the demands of both the Indian Supreme Court and the wide base of consumers is a wait-and-watch game. Until then, there is nothing to do for private players in India’s financial technology industry but to prepare for a careful course re-adjustment.

ENDNOTES:

[1] https://time.com/5409604/india-aadhaar-supreme-court/

[2] https://www.livemint.com/Politics/JufOIND7IUPjnyZCE4BrfL/Aadhaar-is-a-game-changer-Arun-Jaitley.html

[3] https://www.facebook.com/ArunJaitley/posts/jan-dhan-yojana-and-the-1-billion-1-billion-1-billion-jam-revolution-it-is-unlea/676110752577476/

[4] The government has often highlighted that the solution to the extent of social exclusion faced by the e scope of the Aadhaar project goes beyond addressing economic exclusion to include a rural poor in India. Financial and digital inclusion is seen as an effective means to integrate those on the fringes into the social mainstream. The social impact of JAM is measured in terms of reduced income inequality, greater penetration of welfare schemes as well as increased agricultural productivity.

[5] https://economictimes.indiatimes.com/news/economy/finance/aadhaar-helped-modi-government-save-9-billion-nandan-nilekani/articleshow/61064674.cms?from=mdr

[6] https://www.indiatoday.in/technology/news/story/aadhaar-leaks-again-indane-gas-website-app-leak-data-of-6-7-million-subscribers-1459499-2019-02-19. A record of several other such instances can be found athttps://www.medianama.com/2017/04/223-aadhaar-leaks-database/

[7] https://meity.gov.in/writereaddata/files/Personal_Data_Protection_Bill,2018_0.pdf

[8] https://www.sci.gov.in/supremecourt/2012/35071/35071_2012_Judgement_26-Sep-2018.pdf

[9] https://m.economictimes.com/small-biz/sme-sector/the-future-of-aadhar-and-ekyc-based-solutions/articleshow/68251916.cms

[10] https://www.livemint.com/Opinion/DZnXf94JDZXpJ2QkRR9PYJ/Aadhaars-benefits-for-financial-inclusion.html