Authored by: Somiha Chatterjee

Edited by: Avishi Gupta and Riya Singh Rathore

ABSTRACT

Shifting Cultivation is an age-old practice in North-East India. However, with the adoption of neoliberal growth models and the consequent push for high revenue generating modes of cultivation, such as settled agriculture, the practice of shifting cultivation has degraded. This paper re-interrogates India’s position on shifting cultivation and advocates for it’s continuance through implementation of better policies. However, the continuation must account for ways to make the practice sustainable and ensure inclusive rural transformation in the North-East region.

Keywords: Shifting agriculture, north-east region, land, sustainability

CONTEXT

Shifting cultivation [SC] is one of the oldest forms of cultivation dating back to 8000 BC, the Neolithic age. For the people of the North-East region [NER] of India, shifting cultivation has been the dominant mode of food production and the economic mainstay. However, in the last few decades, the states and the central government have heavily targeted the practice as a threat to biodiversity and climate change.

It’s conventionally viewed as an economically inefficient and environmentally hazardous form of cultivation. While critics believe that the practice is hazardous for the environment as it destroys the soil, water, and the region’s flora and fauna (Rahman et al., 2012), various scientific and agroecological studies prove otherwise. Terming this view as a ‘false narrative’, proponents of the practice say that shifting cultivation is perhaps more sustainable than settled agriculture and monoculture; practices that the government overtly promotes in the region (Behera et al., 2016; Kerkhoff and Sharma 2006; Raj 2010)

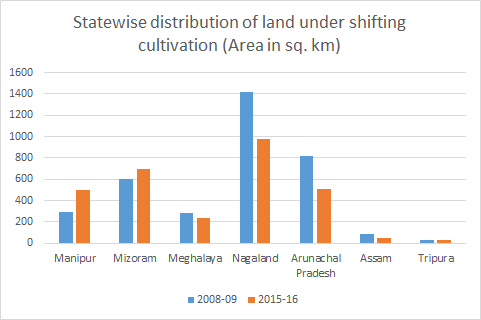

Through policy interventions like the New Land Use Policy [NLUP] 2011, Forest Policy 1988, and Jhum Land Regulation 1948, governments have made consistent efforts to terminate shifting cultivation and replace it with high revenue generating settled-agriculture. However, these policies have been unsuccessful in putting an end to the practice in the region. While the area under shifting cultivation has reduced to some extent, in states like Mizoram and Manipur it has continued to grow (Figure 1). According to a recent NITI Aayog report (2018: 6), about 8500 sq. kilometres of land in the NER is still used for shifting cultivation.

Figure 1: Shifting Cultivation Lands in NEH region of India

Source: Department of Land Resources(2019)

However, these policies have succeeded in degrading the practice, leading to higher carbon emission and biodiversity loss. They also threaten the vast knowledge systems of traditional practices which may be useful for combating existential challenges like climate change and loss of forest cover in the region. In light of these observations, this paper evaluates the existing land-use policies in the region which act as a deterrent to the practice of shifting cultivation. Further, it explores innovations which can help resolve the current situation, wherein government interventions are not taking effect.

UNRAVELLING THE GOVERNMENT’S LAND POLICIES

While India has no policy framework in place to deal with the practice of shifting cultivation, various other policies ranging from forest and agricultural to indigenous policies, affect the practice of SC. Given the immense negative lobbying against shifting cultivation, the underlying premise of most of these policies has been to replace the practice with settled agriculture and allied activities. This replacement is seen by these governments as a profitable venture and as a way to open up possibilities for large-scale development projects in the region (Leblhuber and Vanlalhruaia 2012: 85).

Evaluating the New Land Use Policy (2011)

According to the Mizoram state government, the main aim of the New Land Use Policy is “to put an end to the practices of shifting cultivation by giving the farmers alternative sustainable land-based activities” (NLUP Implementing Board n.d.: 2). Under NLUP, the state provides INR 1 lakh directly to households in the region to facilitate the shift towards alternative livelihoods like horticulture or settled agriculture. While the policy has made an effort to create opportunities for income diversification, its primary objective is to terminate ‘wasteful’ shifting cultivation seems misdirected.