Authored by: Somiha Chatterjee, Akshita Sharma

Edited by: Kavita Majumdar and Riya Singh Rathore

While rural India dodged the first wave of the COVID-19 pandemic, the second wave transmitted into remote communities causing wider destruction. The relief of the receding second wave has been trumped by the threat of a third wave that can be allegedly disastrous for rural India.

The lack of awareness about the pandemic, misinformation about curative healthcare, vaccine hesitancy and inadequacy of the healthcare centres have together created an abysmal socio-economic and health situation in the rural areas. What adds to this dreadful mix and stands to impoverish millions, is the decade-long stagnation of rural wages in India.

Rural Wage Stagnation in India

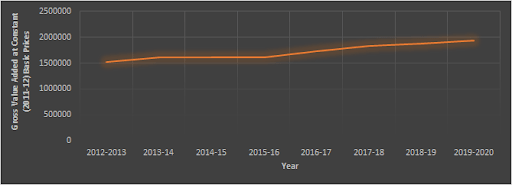

While the rural economy has been steadily growing, as reflected by the Gross Value Added (GVA) reaching INR 19,40,811 crores in 2019-20 (Figure 1), rural real wages depict a different story.

Figure 1: Gross Value Added at Constant (2011-12) Basic Prices – Agriculture, forestry and fishing (₹ crores)Source: Pocket Book of AGRICULTURAL STATISTICS 2019

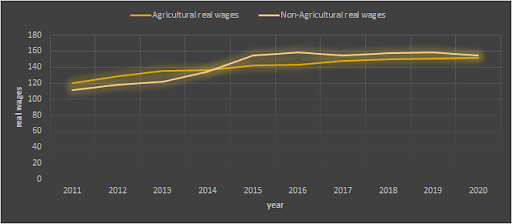

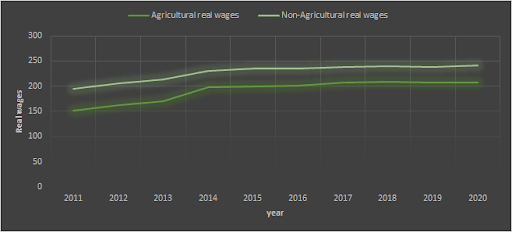

Figures 2 and 3 illustrate the stagnating agricultural and non-agricultural wages for both females and males in the sector. For both genders, non-agricultural occupations have yielded higher wages than agricultural occupations. This can be attributed to the excess supply of labour in agriculture. The kinks observed in 2014-15 is explained by changes in the wage series in 2013. After that year, it is evident that rural wage growth has not been encouraging.

Figure 2: Real Wages (Female)Source: Wage Rates in Rural India

Figure 3: Real Wages (Male)Source: Wage Rates in Rural India

Key Factors Dampening Rural Wage Growth in India

- Slow adjustment of income with inflation: Inflation is the increase in the general price level in an economy which decreases the purchasing power of money one holds. Thus, when inflation rises, nominal wages (in-hand income) must also be increased so that your real wages (purchasing power of in-hand income) also increases. Evidence shows that this is because Indian rural real wages are stubborn in nature. They do not adapt quickly to changes in market conditions. This means that when the economy witnesses price inflation, nominal wages are not adjusted in proportion, and as a result, the real wages fall.

Studies show that this nominal wage adjustment happens only in the long run. Hence, while the rural Cost Price Index (CPI) had increased consistently from 92.8 in 2011 to 154.31 in 2020, the unchanging nature of wages meant real wage growth would not catch up with the price rise.

- Lack of systematic indexation of wages under Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act (MGNREGA): According to former RBI Governor Dr. Raghuram Rajan, the MNREGA wages have increased at a rate much slower than the rate of inflation in various states, which has been a key reason behind the decline in rural wages. The Nagesh Singh report advised indexing the MGNREGA wages to CPI-rural instead of CPI-agricultural as the former was found to be a better indicator of a wage increase.

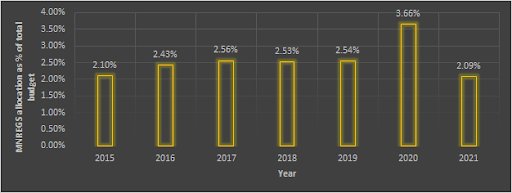

In recent years, the insufficient budgetary allocation towards MGNREGA has been responsible for the program’s failure to improve employment and wages. The allocation towards MGNREGA for 2021-22 has been slashed by 34.52% compared to the revised estimates for 2020-21, which is likely to have a severe impact on rural wages in the coming year given the high dependence on MGNREGA for employment in rural areas.

Figure 4: Budgetary allocation towards MGNREGA as a percentage of the total budget

Source: Official Union Budget data from multiple years.

- Slow down in the construction sector: The construction sector, which grew at a fast pace during 2000-12, slowed down significantly after 2014. Fixed investments in India’s construction sector fell from 19.7% of GDP in 2012 to 15.3% in 2019 and the government’s reduced capital expenditure in 2018 resulted in 15-60% cuts in production by construction companies.

This resulted in a decrease in employment generated via the construction sector and led to slower migration from the rural to the urban areas, dampening rural wages due to excess labour supply in agriculture.

With the onslaught of the COVID-19 pandemic, the situation worsened. The migrant exodus forced by the lockdowns saw the informal sector masses move back to their rural villages. As a result, the rural wages dipped, and the construction sector’s growth slipped to -2.2% in the fourth quarter of 2020.

- Rise in input prices in agriculture: The Indian economy has suffered through two consecutive droughts in 2014-15 and 2015-16, weakening the growth in agricultural GDP and hence, rural wages during this period. The rise in prices of inputs like petroleum and fertilisers and increased vulnerability to international price fluctuations due to increased openness compounded the farmers’ adversity. To add to this, the government was negligent towards the demand for remunerative prices for farm produce, and continuous budget cuts in agriculture-related schemes have worsened the crisis. As the agrarian crisis deepened, the agricultural labourers were worst impacted as their wages declined in the farm as well as non-farm sectors.

Policy Recommendations

- Expand MGNREGA coverage and increase the number of workdays under the scheme. The budgetary allocation for MGNREGA in 2021-22 was reduced from INR 111,500 crore allotted in 2020 to INR 73000 crore in 2021, a decline of INR 38,500 crore as compared to the revised estimates for the previous year. Given the high demand for the scheme in rural areas, the allocated amount might not suffice the people’s employment needs.

- Up-scale skill development programmes to identify skill gaps faced by the rural population and provide training in highly demanded skills in the labour market to boost employment in both agricultural and non-agricultural sectors. Here, technology-induced skill development programmes can help harness rural potential.

- Increase public expenditure in rural infrastructure like the Pradhan Mantri Gram Sadak Yojana (PMGSY) scheme to boost rural non-farm employment and rural wages. An impact assessment of the scheme found that 63% of households saw an increase in average annual income due to the scheme. The allocation for the Rural Infrastructure Development Fund (RIDF) has been increased to Rs. 40,000 crores from Rs. 30,000 crores in 2020, which is a move in a positive direction.

- Increase minimum wages to meet expert committee recommendations. While the Code on Wages 2019 mandates a universal minimum payment of INR 178 per day, it is still less than half of the national minimum wage of INR 375 per day, recommended by an expert panel appointed by the Labour Ministry.

- There is a need to strengthen agriculture into being more remunerative and resilient. While the allocation for Pradhan Mantri Kisan Samman Nidhi (PM-KISAN) scheme has been reduced by about 10,000 crores this year compared to the budget estimate of 2020-21. While India ranked 7th on the Global Climate Risk Index in 2021, the government slashed the Environment Ministry’s budgetary allocation by INR 230 crores. The lack of emphasis on ensuring the sustainability of the agricultural sector directly impacts the wages of the people involved in farming and allied activities.

About the authors:

Akshita Sharma is a Research Associate at the Social and Political Research Foundation. Her work focuses on gender, public health and, social and behaviour change.

Somiha Chatterjee is a Research Assistant at the Social and Political Research Foundation. Her work focuses on economy, environment and gender.