Authored by: Shubhangi Priya

This piece attempts to explore the relationship between the historical criminality of rape and the laws which govern sexually violent behaviour in India. The Bombay High Court’s affirmation of the constitutional validity of Article 376E, which sanctions the death penalty in cases of multiple sexual offences, presents an urgent inquiry into the gaps between the policy-making and policy-implementation processes. On one hand, this declaration of the Bombay High Court asserts its legal stance on the criminality of rape, while on the other hand, the administration which it represents, undermines the structures and norms that legitimise it in India’s social order. Thus, it is pertinent to analyse the gaps in the operationalisation of political reform, which undoubtedly influence actual, lived experiences of women and children who become victims of rape.

The evolution of rape laws in India has garnered significant attention in the wake of widely protested rape incidents in India. Treatment of, and response to rape in the legal framework of Indian governance post-1947, certainly provide a nuanced understanding of the socio-cultural context in which these laws developed. While combating oppression and suppression of women has always been the face of India’s shift from tradition to modernity, the scant systematic analysis of the social influence of anti-rape laws establish an inadequacy in the approach to conceptualise crimes against women, by neglecting the accounts of socially lived experiences of women who become victims of it.

The Bombay High Court’s landmark upholding of Article 376E in June 2019, in the case of the gang rape of a photojournalist in Mumbai by five men, seeks to establish a no tolerance approach to rape. Yet their claims offer no security to the women of India, who fear violence every time they access public or private transport. It may be argued that such a stance upheld by the Bombay High Court adds to the discourse of change undertaken by the Indian people to put a stop to sexual violence against women, especially taking into account the nationwide protests post the gang rape of Jyoti Singh in 2012. The Criminal Law (Amendment) Act of 2013 (also known as the Nirbhaya Act), which emerged as a reaction to the incident, included newer definitions of what constituted ‘sexual assault’ [1]. However, even in its improved version, the amendment had little effect on how Indian women perceived their own security, as it focused solely on expanding the legal scope of sexual harassment and assault, thereby abandoning the imperativeness of policy recommendations which are grounded in rigorous impact evaluations [2] and community-based, social sector programs [3].

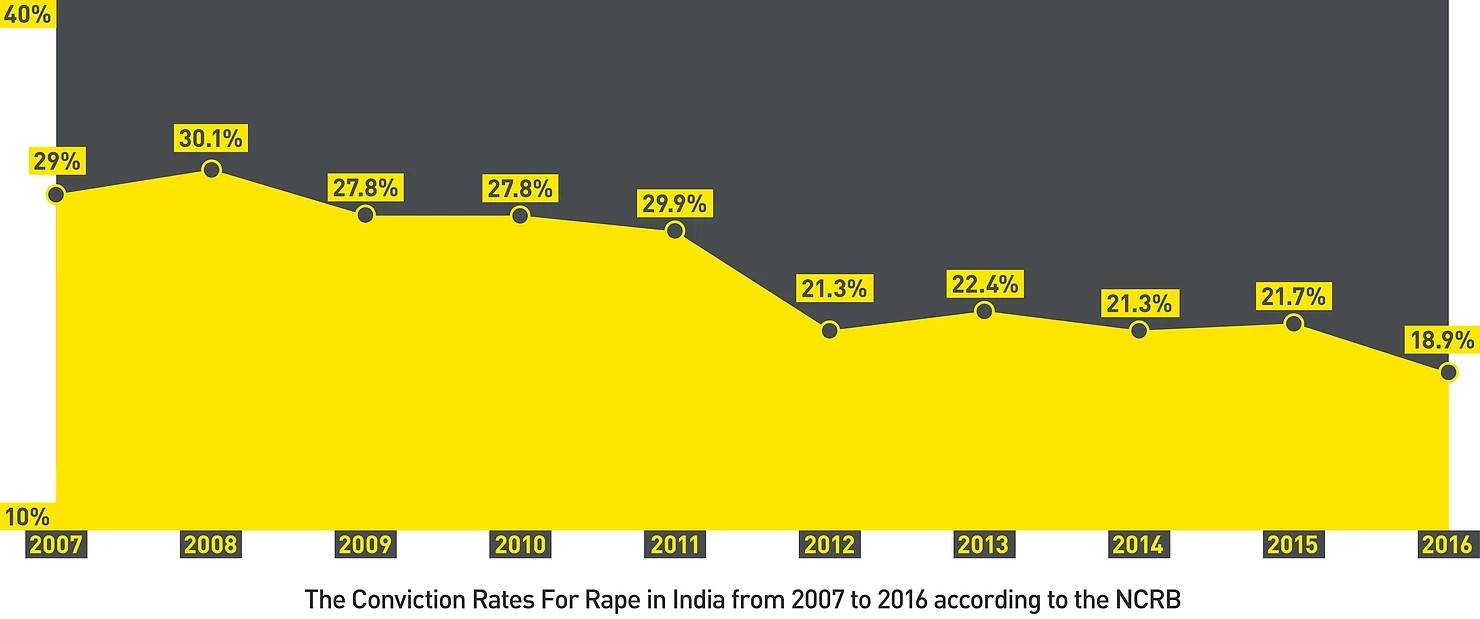

While the rate of reported rapes indicated an increase of 3.03% from 2017 to 2018, according to data published by the Delhi Police, the individual cases of rape alone have increased (from 757 in 2017 to 780 in 2018) [4]. Commenting on the interventions of police into rape cases in the national capital, especially ones that occur within the private sphere of women’s lives, it can be observed that even though reporting of rape to law-enforcement agencies is certainly a marker of changes implemented in the legal system, the rate of conviction, at 18.9% in 2016, remains low [5]. The falling conviction rate, in this sense, signifies not only the inefficient interventions made by the police into investigations of the cases, but also a systemised disbelief of the victims of rape. Such a trend unarguably enroots the burden of proving that rape has been committed in the victim, minutely making women apprehensive of taking legal action against their attackers. Thus, the falling conviction rate, in tandem with the larger system of justice, perpetuates an air of dismissal of the crime that has been committed against them, adding to the mental, emotional, and physical trauma already borne by them. In this regard, the establishment of forensic labs dedicated to matters regarding sexual assault, as well as rape crisis centres, may offer some respite to rape victims in easing the process of lodging complaints and undergoing medical examinations for evidence [6].

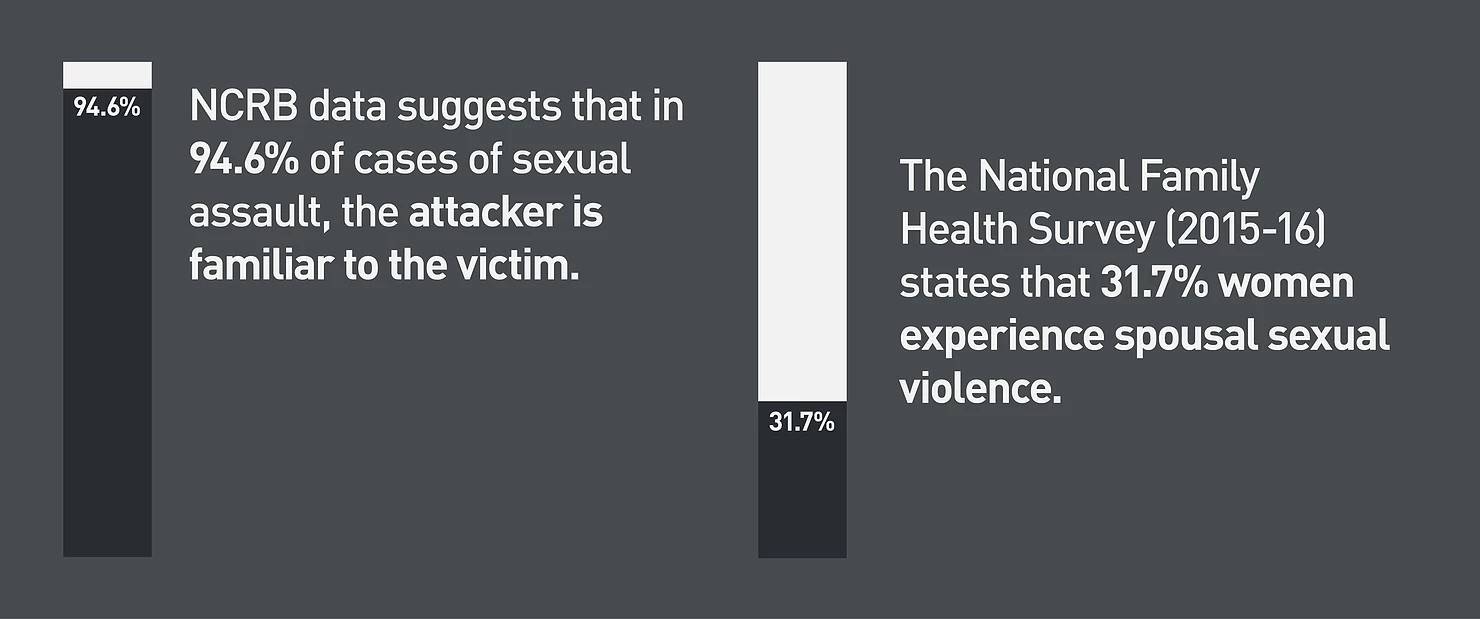

Another factor that remarkably contributes to the reporting and conviction of rape is the perpetrator being known to the victim. Data suggests that in 94.6% of the cases of sexual assault, the attacker is familiar to the victim. Further, according to the National Family Health Survey (2015-16), the percentage of married women who experience spousal sexual violence in both urban and rural settings is 31.1% [7]. This figure demands an examination of the phenomenon of marital sexual assault in India, which is noticeably excluded from the definition of rape in the Criminal Law (Amendment) Act of 2013. As such, sexual assault of married women does not fall under the ambit of this legislation, further reiterating the orthodox conceptions of marriage in Indian society, where wives are considered the property of their husbands. Indeed, such an ‘ownership’ of married women implies the regressive state of rape laws in India, that pose an impediment, especially to the security and agency of married women [8].

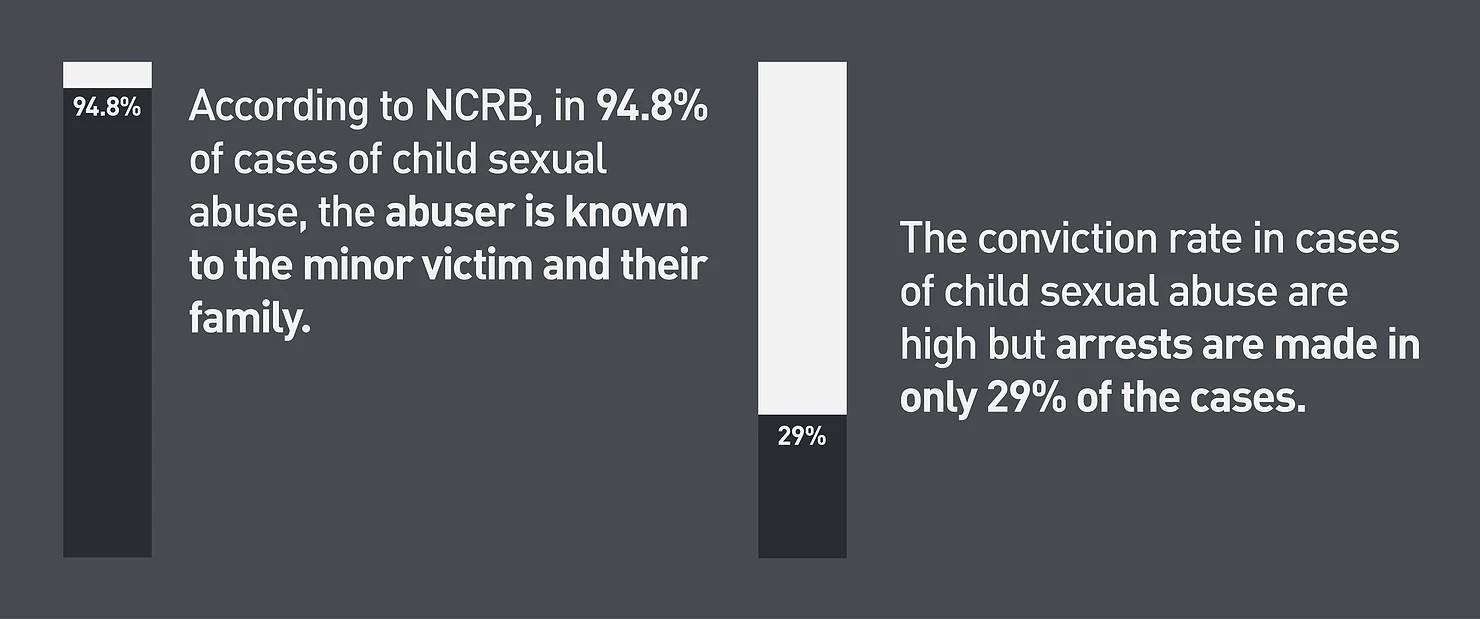

Evidently, while such experiences shape the way women choose to live their lives, it would be remiss to not consider sexual violence committed against minors. The abduction, gang-rape, and murder of an 8-year-old in January 2018 sparked outrage all over India, prompting Indian lawmakers to amend the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences Act (POCSO) of 2012. Its amendment ordinance proposed a minimum of twenty years of imprisonment and/or capital punishment for committing penetrative sexual acts against a child below the age of 12. Its implementational gaps, however, include not only the police’s unenthusiastic probes into offences against the minor victim, but also the archaic legal proceedings that govern the process of delivering justice. The social implications of the POCSO Act, which, despite being radical in nature, tends to be viciously caught up in bureaucratic red-tapism extant in the administration of the Indian legal system. This includes, but is not limited to, the police’s administrative and investigative proceedings, as well as routine instances of bribery and corruption by perpetrators [9]. The punishment for sexual assault committed against a child is the death penalty, yet data suggests that even though the conviction rate is high, arrests are made only in 29% of child sexual abuse cases [10], and factors such as the abuser being known to the child victim and their family contribute to reasons why children do not disclose its occurrence. The National Crime Records Bureau cites a percentage of 94.8 in its study of reported cases of child sexual abuse in 2015, that relates to children knowing their abusers in familial or educational settings. In this context, the POCSO Act fails to provide the very protection that its name includes [11].

Such a discord between policy-making and policy-implementation demonstrates the partiality of the perspectives of lawmakers concerning issues relating to sexual assault of women and children. It challenges the appropriateness of law-making, which is restricted to developing and amending policies, without taking into account the multi-layered social reality of women and children who become victims of violence. This law-making process fails to include the ground-level consciousness of men who exercise their masculinity through fallacious ideas of control and power. It overlooks a comprehensive visualisation of women-centric policies, further embedding deep-seated patriarchy in the politico-legal institutions of India, which falsely project ideas of change and modernity, thereby solidifying the gap between political reform and social reform [12].

ENDNOTES:

[1] The Criminal Law (Amendment) Act, 2013, now includes acid attacks (Section 326A), attempt to acid attack (Section 326B), sexual harassment (Section 354A), acts with intent to disrobe a woman (Section 354B), voyeurism (Section 354C), and stalking (Section 354D) of the Indian Penal Code

[2] https://www.jstor.org/stable/40282335?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents

[3] https://www.jstor.org/stable/26605071?seq=1#page_scan_tab_contents

[4] https://www.newsclick.in/rise-reported-rape-cases-2018-police-data-reveals

[5] https://thewire.in/gender/conviction-rate-crimes-women-hits-record-low

[6] https://www.jstor.org/stable/i23391082

[7] http://rchiips.org/nfhs/pdf/NFHS4/India.pdf

[8] https://www.jstor.org/stable/i40163194

[9] https://www.thehindu.com/opinion/lead/a-task-only-half-finished/article5065462.ece

[10] https://www.d2l.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/01/all_statistics_20150619.pdf

[11] https://www.savethechildren.in/resource-centre/articles/recent-statistics-of-child-abuse

[12] https://www.jstor.org/stable/i24890238