Authored by: Niha Satyaprakash

Edited by: Riya Singh Rathore and Yamini Negi

Abstract

The rising use of economic sanctions as a negotiation tool has shown a decline in military aggression and warfare between rival countries. However, the evidence regarding sanctions’ effectiveness in obtaining political concessions is inconclusive since sanctions apply to vastly different political and economic situations. Through a historical analysis of the use of sanctions, this issue brief identifies the political variables that may promote the efficacy of sanctions. It further asserts that even the most effective sanctions, however, have devastating effects on the living standards of ordinary people. Hence, caution is necessary while applying sanctions.

What are sanctions?

Today, most countries store sanctions as a weapon in their foreign policy arsenal. Sanctions are best defined as the introduction of penalties employed against a state or other entity with the purpose of altering its behaviour (Haass 1998). As a lower-cost and lower-risk substitute to physical warfare, sanctions allow countries or multilateral institutions to coerce, deter, punish or shame entities that have violated international norms of behaviour, or simply aggravated the sanctioning party (Masters 2019).

Sanctions can take various forms, ranging from diplomatic embargos to sanctions on the environment. The most commonly used are economic sanctions (Masters 2019), which include measures such as arms and related materials embargo, asset freezes, export and import restrictions, financial prohibitions, technical assistance restrictions.

The efficacy of economic sanctions, hereafter referred to as simply ‘sanctions’, as a policy tool is widely debated. Critics argue that in today’s globalised economy, sanctions prove highly costly for the country that imposes them (The Week Staff 2021; The Economist 2020). In the case of sanctions against large countries like Russia or China, countries lose access to thriving markets and bear the brunt of retaliative measures.

Many like Peksen (2019) argue that sanctions are often unsuccessful in changing the targeted country’s leaders’ behavior and instead negatively impacts civilians. Proponents of sanctions argue that this short term, misplaced deprivation is justified if the desired change is affected in the long term. However, authoritarian leaders who commit atrocious human rights violations are likely to resist and predict external pressure. Even if faced with anti-state protests from angered civilians, critics argue that authoritarian leaders are often able to use coercive state apparatus to crush dissent (Haass 1998). With inconclusive evidence, this debate is not likely to have a clear winner.

A large body of economic literature, through the help of rigorous quantitative tools, demonstrates that economic sanctions have dismal success rates (Hufbauer and Schott 1985). However, these studies do not account for cases where the threat of a sanction in itself was successful in obtaining concessions. Such a case seems to indicate that, in principle at least, sanctions have the potential of yielding desirable outcomes. The problem lies in implementation strategies (Drezner 2003).

This warrants an inquiry into the historical conditions leading to sanctions, their subsequent popularity, and consequences. A comprehensive analysis of this political context helps in identifying key features of successfully implemented sanctions.

Sanctions: A Historical Overview

The use of economic or financial pressures to achieve political ends is likely to be as old as trade itself. The first recorded use of sanctions was in 432 BCE when the Athenian Empire banned traders from Megara, a rival city-state (The Economist 2021a). Despite being a long established political tool, Coates (2020) notes that modern concepts of international sanctions only became prominent in the 20th century. Sanctions are now a mechanism to enforce global order through a collective denial of economic access.

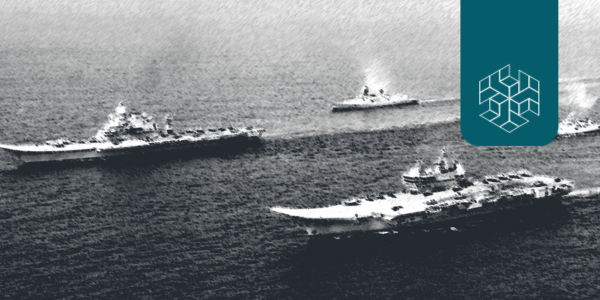

Initially, economic warfare was not a tool that prevented violence but rather one that intensified it. This perspective shifted as the world grew more economically interdependent and people realised how powerful sanctions are. After World War I, leaders worldwide agreed on using embargos as an economic weapon to punish aggressors. The League of Nations Covenant institutionalised this, mandating an automatic and collective sanction against any nation that started an aggressive war (Bottelier 2019).

Ethiopian leaders appealed to the League for assistance after Italy invaded the country in 1935. In response, the League imposed crippling sanctions on Italy, to no avail. Not only were Italian troops able to complete their conquest, but the sanctions also drove Italy into the orbit of Nazi Germany (Coates 2020). To that end, the League of Nations’ affair with sanctions was far from successful.

Several other developments also occurred during this period. One of the more notable ones being the passing of the Trading with the Enemy Act [TWEA] by the United States of America during World War I. TWEA prevented trade with Germany and also authorised the seizure of German property in the USA. While this did keep a significant amount of money out of Germany’s reach, it did not deter the Nazis from territorial conquest. American President, Franklin D Roosevelt, also invoked TWEA after Japan invaded Indonesia in 1941. The government seized all Japanese assets in the USA to coerce Japan into renouncing its territorial conquests. However, this economic aggression only invited retaliation from Japanese hardliners, who deployed military force in response (Coates 2018).