Authored by – Neymat Chadha

Edited by – Kavita Majumdar

CONTEXT

Street vendors are an integral, and yet, an overlooked part of India’s urban landscape. Constituting one of the largest segments of self-employed workers, India is estimated to have over four crore people carrying out a diverse range of street vending activities [1]. The Street Vendors Act 2014 identifies urban street vendors as constituting up to 2.5% of a city’s population. With a daily turnover of INR 80 crore, street vendors contribute to about 14% of India’s non-agricultural urban informal employment sector.

Street vending entails a variety of activities catering to both goods and services, ranging from selling fruits, vegetables and water on carts, stalls and mobile trolleys to selling affordable clothes and street food. Street food vendors ensure food security for a large section of India’s urban poor. With an alarming percentage of India’s population living below the poverty line, street vending as a form of self-employment with relatively lower capital inputs and flexible working hours has emerged as a viable employment opportunity for many. The median monthly earning of a street vendor in India is about INR 7000 [2].

Amidst rapid urbanisation, despite being a critical part of India’s vast informal economy, the everyday struggle of street vendors has intensified over the years. Article 19(1)(g) of the Indian Constitution states that every citizen of India has the right to practice any profession or carry out any occupation. Yet, in everyday conversations, street vendors are often considered to be illegal occupants of the streets – ‘suggesting lawlessness (‘encroachments’), filth (‘eyesores’) and danger (‘menace’)’ and an obstruction or a nuisance [3][4].

In the absence of a national policy for street vendors and the fragmented and inadequate implementation of relevant legislations, some grave structural issues affecting street vendors have come to the fore. The following analysis provides an overview of laws pertaining to street vendors in India. It focuses on the problems gripping the ‘informal’ nature of street vending, often viewed in a misconstrued manner from the lens of illegality.

STREET VENDING LEGISLATIONS IN INDIA AND THEIR IMPLEMENTATION

The Street Vendors (Protection of Livelihood and Regulation of Vending) Act 2014 (SVA, hereafter) defines a street vendor as an individual engaged in ‘vending of articles, goods, wares, food items or merchandise of everyday use or offering services to the general public, in a street, lane, sidewalk, footpath, pavement, public park or any other public place or private area, from a temporary built-up structure or by moving from place to place and includes hawker, peddler, squatter and all other synonymous terms which may be local or region-specific’. Several legislative acts such as The Bombay Provincial Municipal Corporation Act (1949), the Bombay Police Act (1951) and the Improvement Trust Acts (for city planning) were enacted under the British rule and retained as it is, which are now outdated [5].

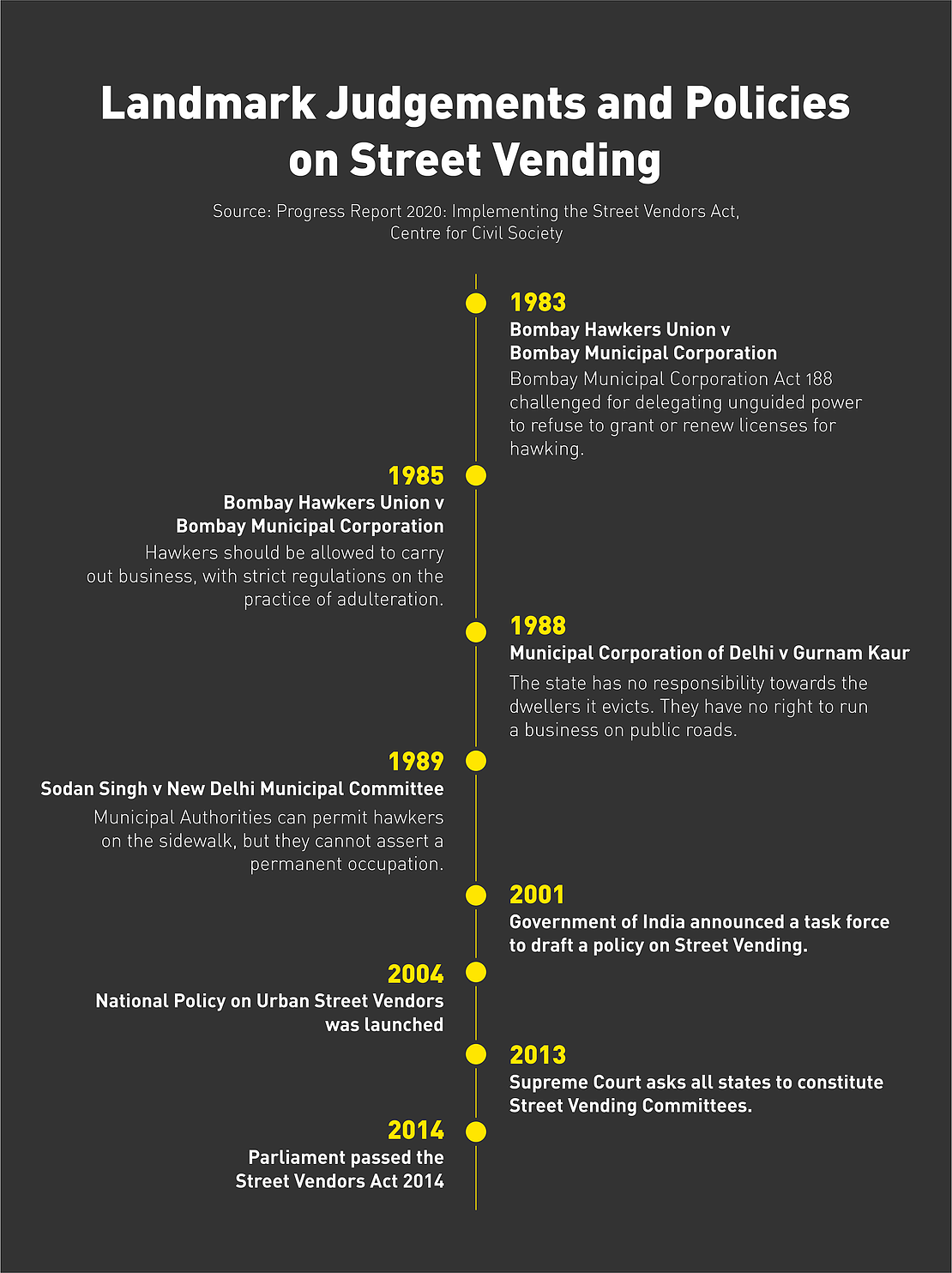

Post-independence, street vending emerged as a critical policy issue through a 1985 ruling by the Bombay High Court – Bombay Hawkers Union v Bombay Municipal Corporation. This lead to the first attempt towards legalising street vending through proper licensing and demarking hawking and non-hawking zones [6].

Figure 1

Source: Progress Report 2020: Implementing the Street Vendors Act, Centre for Civil Society

In 2004, the Indian government passed policy guidelines focusing on the improvement and management of street vendors with a provision for Town Vending Committees (TVCs) as facilitators between street vendors and the local municipality. However, these guidelines had little to no regulatory mechanism to monitor their implementation. After an amendment in 2009, the Parliament passed the SVA in 2014. However, the federal structure of governance allows each state to formulate its independent policies, in close coordination with local bodies.

Hailed as the first step towards legalising street vending, the SVA aims to provide a national framework to protect the rights of urban street vendors and to regulate street vending activities through the formulation of TVCs. As part of the Act, the constitution of TVCs with 50 per cent representation of vendors and their organisations was made mandatory, with at least ⅓ from women [7].

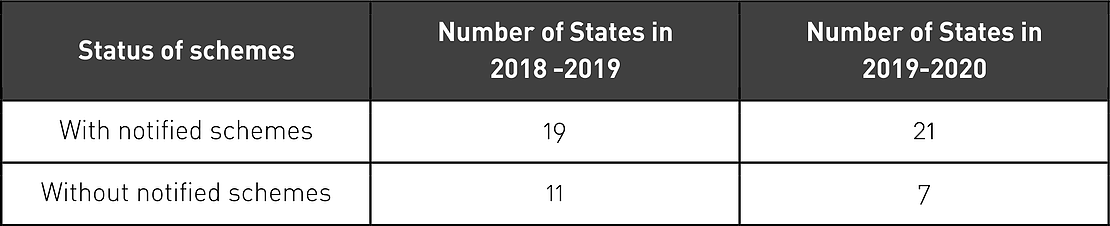

While some states such as Andhra Pradesh have progressed in implementing the Act with all towns constituting TVCs, in many states, it has been reported that over 42 per cent of the TVCs have inadequate representation from members of the vending community [8]. Seven states including Assam, Haryana, Karnataka, Maharashtra, Madhya Pradesh, Puducherry and Uttarakhand have not notified schemes, whereas Telangana and Uttarakhand are yet to notify rules pertaining to various schemes for street vendors [9].

Table 1: Number of States with and without Notified Schemes

Source: Progress Report 2020: Implementing the Street Vendors Act

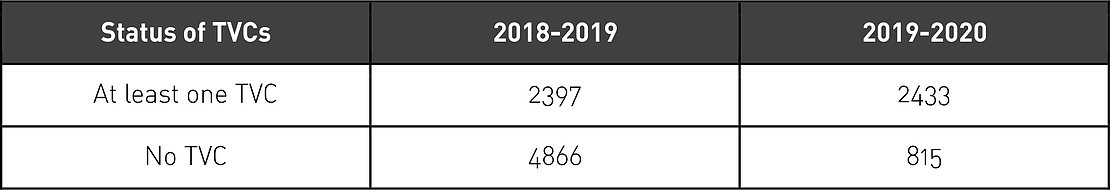

Table 2: Number of ULBs with Town Vending Committees

Source: Progress Report 2020: Implementing the Street Vendors Act

In one study, of the 3,248 Urban Local Bodies (ULBs) covered, less than 131 ULBs meet the requirements for top ULBs [10]. While Haryana has identified over 1 lakh street vendors, it has issued identity cards to 1,000 vendors, and no vendors have been issued vending certificates [11]. According to a 2017 study conducted among 25,000 vendors in Bengaluru, only 17% were issued permits, making them prone to unwarranted extortions and evictions, despite evictions being prohibited under section 3(3) of the SVA [12].

OCCUPATIONAL CHALLENGES AND THE PANDEMIC

Occupational safety and the hazardous working conditions of street vendors often evade urban policy formulation. In 2013, the National Association of Street Vendors of India (NASVI) voiced their concern about the increasing harassment, torture and violence by police and municipal authorities against street vendors, especially women[1]. According to another study, it is estimated that street vendors spend roughly 10-20 per cent of their incomes in bribes to tackle unwarranted evictions and penalties from municipalities and police authorities [13]. In Mumbai itself, the collection of penalties and redemption charges at Mumbai Municipal Corporation amounted to US $1.5 million, and ‘haftas’ (informal payments) amounted to US $17 million per year [8].

On 23 September 2020, the Parliament passed three major labour code bills – Occupational Safety, Health and Working Conditions Code, 2020; the Industrial Relations Code, 2020; and the Code on Social Security, 2020. However, wage workers, domestic workers, bidi makers and street vendors do not fall under the ambit of the social security code [14].

Due to the ongoing COVID pandemic and the subsequent lockdown, India has witnessed a 40 per cent fall in consumer spending as compared to last year [15]. As a consequence, the streets of Indian cities have become unusually silent. Due to the suspension of weekly markets, fewer travellers at railway stations and bus stops, there are barely any buyers on the streets, thus leading to the inevitable stagnation of the everyday livelihood of street vendors. Similarly, the lockdown has impacted the informal sector, which, in turn, has affected the street vendors. For instance, with the shutting down of the wholesale clothing market, the diverse low circuit economy which supplied thread and packaging material, among others, has taken a hit [1].

On 1 June 2020, the Ministry of Housing and Urban Affairs (MoHUA) announced that as a part of the Prime Minister Street Vendor’s AtmaNirbhar Nidhi (SVANidhi) scheme, a working capital loan of INR 10,000 would be provided to street vendors, to be repaid in monthly instalments within one year. The scheme does not entail non-repayable financial assistance and only seeks to cover 50 lakh street vendors against an estimate of over four crores [16]. However, on 22 September 2020, the MoHUA identified the presence of only 18,25,1776 registered street vendors in India, with no data from New Delhi, revealing a discrepancy in the actual number of registered street vendors in India as opposed to the beneficiaries on paper[2]. Moreover, it has been reported that in Delhi, there are ‘zero registered street vendors’. While over 1.3 lakh street vendors registered with the New Delhi Municipal Council and three Municipal Corporations back in 2007, this only gave them access to ‘tehbazaari’ (temporary vending rights) [17]. These vendors were then issued ‘red slips’ as a marker for identification, however, ‘tehbazaari’ was reportedly never renewed. Hence, the street vendors were not registered, rendering the schemes mentioned above futile and inadequate for the beneficiaries.

END NOTES

[1] https://thewire.in/labour/street-hawkers-lockdown [2]https://www.livemint.com/news/india/stark-reality-of-the-self-employed-11569864413483.html [3]https://www.wiego.org/sites/default/files/resources/files/Street%20Vendors%E2%80%99%20Laws%20and%20Legal%20Issues%20in%20India.pdf [4]https://thewire.in/society/street-vendors-urban-public-spaces [5]https://www.wiego.org/sites/default/files/resources/files/Street%20Vendors%E2%80%99%20Laws%20and%20Legal%20Issues%20in%20India.pdf [6]https://www.researchgate.net/publication/295081448_Symbolic_politics_legalism_and_implementation_the_case_of_street_vendors_in_India [7]https://www.thecitizen.in/index.php/en/NewsDetail/index/9/3858/The-Harassed-Street-Vendors-of-India [8]https://www.asianstudies.org/publications/eaa/archives/the-ease-of-doing-business-on-the-streets-of-india/ [9]https://ccsindia.org/sites/default/files/progress-report-2020-implementing-the-street-vendors-act.pdf [10]https://ccs.in/research#progress-report [11]https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/chandigarh/hry-fares-poorly-in-welfare-of-street-vendors-report/articleshow/76394781.cms [12]https://bengaluru.citizenmatters.in/forum-urges-bbmp-to-cover-all-street-vendors-of-bengaluru-in-the-survey-26291 [13]https://www.academia.edu/21230934/A_STUDY_ON_THE_ORGANIZING_OF_STREET_HAWKING_BUSINESS [14]https://www.businesstoday.in/current/economy-politics/new-labour-laws-are-pro-business-anti-workers/story/417064.html [15]https://www.crowdfundinsider.com/2020/08/165509-consumer-spending-in-india-is-significantly-lower-due-to-covid-19-related-uncertainty-upi-and-digital-payments-also-decline-as-lockdowns-eased/ [16]https://delhipostnews.com/street-vendors-and-the-state-the-quest-for-legality/ [17]https://thewire.in/rights/delhi-street-vendor-loan-tehbazaari