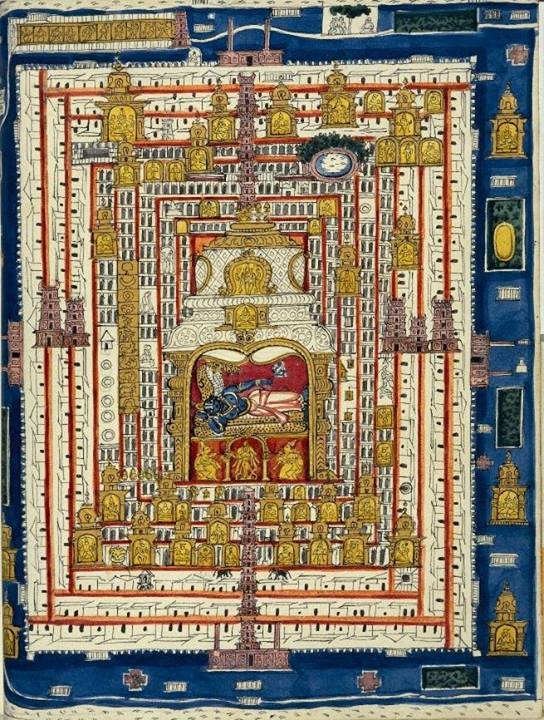

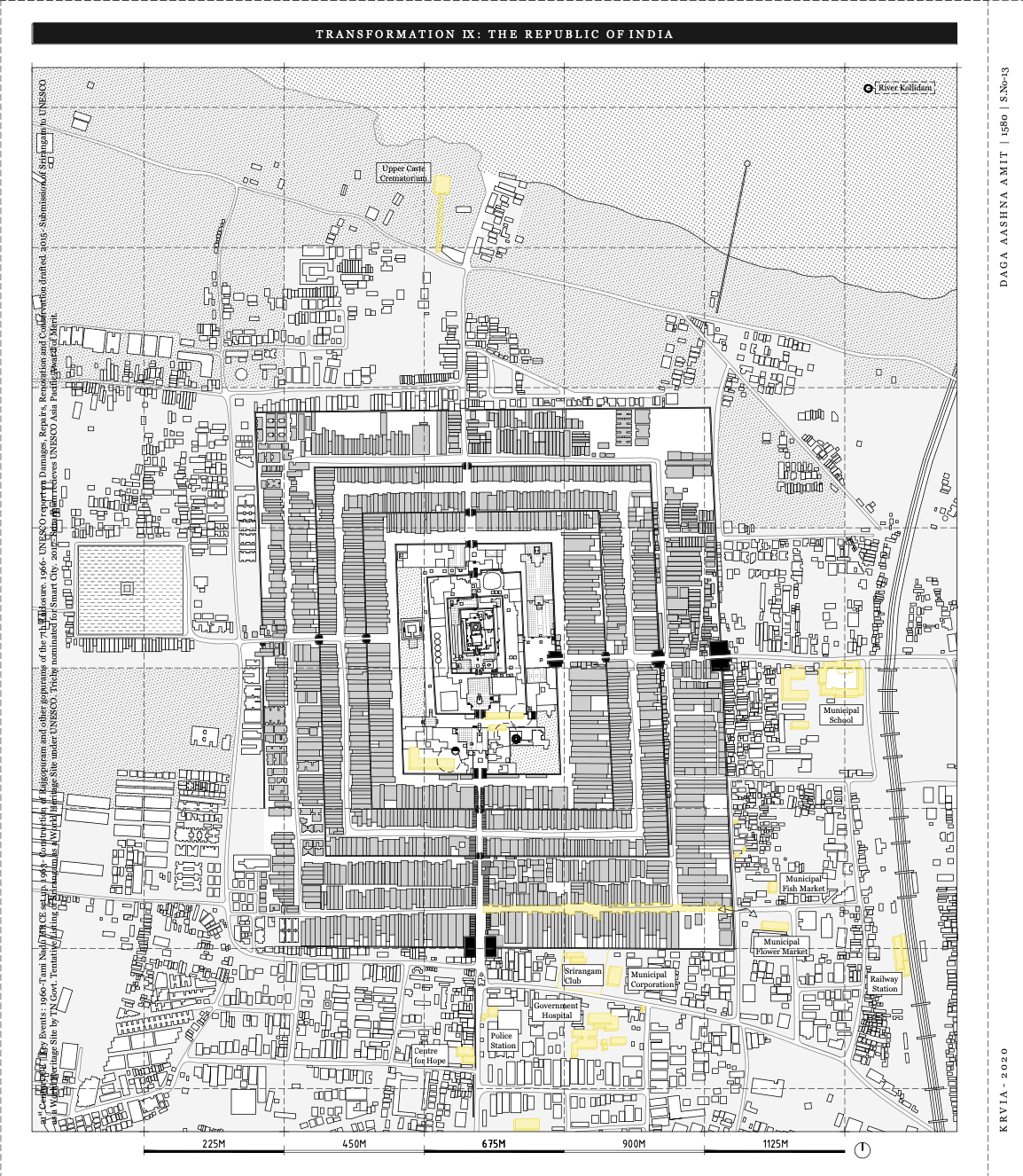

The Kaveri delta begins 16 kilometres west of Tiruchirappalli, where the river Kaveri splits in two, the Kaveri and the Kollidam, to form the island of Srirangam. The photo story captures the neighbourhood which falls under the administration of Tiruchirappalli City Municipal Corporation and is navigating complex ecological, geographical, and governance problems. With a population of 2,74,000 people, important historical sites, and surrounding agricultural lands, Srirangam is home to the largest functioning temple in the world, the Sri Ranganathaswamy temple, which covers an area of 156 acres [1]. The Sri Ranganathaswamy Temple is enclosed within seven concentric enclosures with courtyards on an island formed between the Kaveri and the Kollidam river.

Srirangam’s literature traces back to the 5th century CE when the island is said to have formed as a permanent seat for a Vishnu idol, catalysing the process of making the city sacred. The island was believed to be a replica of the cosmic world on land, a utopia with fertile soils, lush forests, and flowing rivers, protected from all sides on account of the river splitting into two, the Kaveri and the Kollidam [2]. With the Temple governing the city, Srirangam became the urban centre of socio-economic and political power, administrating large swathes of land and villages [3] [4].

The most important aspect of the temple town is its geography. It lends the neighbourhood a symbolic presence that transcends Tiruchirappalli’s own. The ethereal landscape has not only formed the identity of Srirangam as a town but also the people of the city. However, today the land is surrounded by dry and dead riverbeds amidst sweltering heat. The river bank of Kaveri is now confined to the ebbs and flows of multiple dams built across the delta, with Kollidam being solely reserved as a flooding river in case of an overflow or breach of the dam. Srirangam, originating from the word ‘arangam’ in Tamil, meaning an isle in the midst of a river, has ceased to be an island by definition.

Unlike the 2nd century CE Grand Anicut Dam (Kallanai), which was part of a larger ancient irrigation network, the construction and remodelling of dams along the Kaveri in the 19th and 20th centuries changed the terrain of and around the rivers. The Upper Anicut Dam, built by the British in 1836, completely restricted the flow of water to the Kollidam in order to meet the increasing requirement of water further east of the island. This practice resulted in Kollidam being dry throughout the year in the current age.

The construction of the largest dam on the river course, the Mettur Dam, was built in 1934 with the intention of generating hydroelectric power and providing a major source of irrigation in the State. Today the excessive exploitation of the river has exacerbated the water crisis, resulting in the Tamil Nadu and Karnataka disputing over water, with major implications for the everyday life of people.

Placing such a rigid structure as an intermediary between the natural resource and its consumer has created a shift in the narrative around water. While decentralised small-scale water management systems are directly associated with the landscape, modern-day droughts and the declining water level in the Kaveri are associated with the Tiruchirappalli City Corporation and its allied infrastructure. The city places the onus of the natural resource on government bureaucracy instead of acknowledging the changed ecology and natural landscape of the region.

Srirangam’s loss of its natural rivers not only changed the resident’s engagement with the land but also caused a disengagement of the larger society from its immediate landscape and context. Wooded forests were replaced with agricultural lands and empty rivers with borewells.

This further resulted in the displacement of people relying on the river. Professions relying on the river as their main income sources, such as indigenous farmers and cattle herders, were forced to move out of the island and seek alternate jobs.

Empty rivers increased the dependence on groundwater and the use of borewells which depleted water even further. Water wells situated within each individual house inside the enclosures have been rendered unusable and sacred rituals of the temple now involve drawing water from mechanised borewells near the dry riverbed instead of the actual river.

By losing the revered rivers that the island originates from, the built environment centred around the utopian myth also has slowly disintegrated. The ancestral residence of Ranga Sethi, a Srirangam resident and professor by practice, is situated in the fifth enclosure of the temple town. The courtyard, which once had a well, is now breached by sewage water. Such everyday problems reveal a unique arrangement of governance on the island.

Sethi’s residence shared a boundary wall the South Chitra Street, one of the primary professional paths for the festivities. While the land with the seven enclosures is owned by the Temple, a matter disputed currently at the Madras High Court [5], the residents’ buildings on the enclosure land fall under the administration of the municipality. Interviews with the locals reveal that it is for this reason that the older sanitation system consisting of discharging waste in the Aradi Sandu (a six feet wide back lane now consisting of soak pits and septic tanks) cannot be replaced with municipality-provided underground drainage. Processions cannot be conducted on the same streets which pit in the Aradi Sandu. They require manual cleaning, for which labour is sourced from outside the district [6]. Such clashes between the residents and temple authorities are omnipresent on the island.

Increased tourism and urbanisation on the island have highlighted the lack of infrastructure and resulted in the uncontrolled discharge of polluted water. Groundwater is exploited and rendered unusable due to poor sewage discharge and treatment systems. The lowered ground water table has also affected the foundations of the heavy gopurams on the island. Almost a decade after the city was nominated under the Smart City Mission, the development plan keeps the seven enclosures out of its planning purview.

Srirangam has not been identified as a special area as per the Town Planning Act. Therefore, laws have not been updated to keep up with the capital influx and growing tourism-led development. Even though the Tamil Nadu Ground Water (Development and Management) Act of 2003 was introduced to conserve and regulate groundwater usage, it is increasingly difficult to control exploitation of the resource and ensure recharge when necessary alternatives are not plugged in.

Increased tourism and urbanisation on the island have highlighted the lack of infrastructure and resulted in the uncontrolled discharge of polluted water. Groundwater is exploited and rendered unusable due to poor sewage discharge and treatment systems. The lowered ground water table has also affected the foundations of the heavy gopurams on the island. Almost a decade after the city was nominated under the Smart City Mission, the development plan keeps the seven enclosures out of its planning purview.

Srirangam has not been identified as a special area as per the Town Planning Act. Therefore, laws have not been updated to keep up with the capital influx and growing tourism-led development. Even though the Tamil Nadu Ground Water (Development and Management) Act of 2003 was introduced to conserve and regulate groundwater usage, it is increasingly difficult to control exploitation of the resource and ensure recharge when necessary alternatives are not plugged in.

At Srirangam, drastic changes in the riverscape have revealed critical linkages between ground ecology, governance, and development. The loss of the river, increasing conflicts within the governance systems and lack of due development and opportunities have pushed residents outside the island. The ecological crisis comes into being in different forms in different geographies. Amidst development, it is critical to ensure that natural resources and their consumption sync in a manner that allows for future protection of the resource and, by extension, humankind. By highlighting histories that land bares, one allows for dignified and equitable resource distribution.

The situation at Srirangam is a constant reminder that the myth of utopian cities is situated within a much larger reality, one where dead landscapes continue to ‘modernise’ our everyday life, where policy and governance systems continue to shape our daily realities, and where progress follows a language alien to the land and yet global to the world.