Written by – Jitendra Bisht

Edited by – Kausumi Saha

CONTEXT

On 21st September 2020, the Rajya Sabha passed two key bills related to reforms in agricultural marketing and trade, amid protests from opposition parties as well as farmer and trade unions across Punjab, Haryana, and several other states. After receiving the assent of the President on 27th September 2020, the Farmers’ Produce Trade and Commerce (Promotion and Facilitation) Bill 2020 (FPTC, hereafter), and the Farmers (Empowerment and Protection) Agreement on Price Assurance and Farm Services Bill 2020 (FAPAFS, hereafter), which were earlier brought in as ordinances to the Lok Sabha, have now become Acts. A third bill to amend the Essential Commodities Act 1955, which was passed by the Rajya Sabha on 22nd September, has also received the Presidential nod. While the Prime Minister has called the passing of the two farm laws in Rajya Sabha a “watershed moment in the history of Indian agriculture”, farmers’ organisations like the Bhartiya Kisan Union as well as several trade unions have been calling for their rollback for over a month now [1]. In this context, the following analysis attempts a needs-based assessment of the FPTC and FAPAFS and looks at some of their practical implications.

KEY PROVISIONS AND THEIR RATIONALE

The FPTC brings in two broad changes to agricultural marketing [2]:

- It allows farmers, traders and any e-trading platform to carry out inter-state and intra-state sale and purchase of farmers’ produce in a ‘trade area’ [3].

- It also allows trade of agricultural produce outside the physical premises of notified markets under various State agricultural produce market committee (APMC) acts.

In line with these changes, the FPTC seeks to abolish all types of fee and cess under the State APMC acts and other laws on farmers and traders transacting in trade areas. The only necessary requirement for traders to be able to freely purchase farm produce physically or through an e-trading platform will be a PAN card. The FPTC also proposes creation of a Price Information and Market Intelligence system so that farmers can make a more informed sowing choice based on prior knowledge of crop prices and shifts in demand.

The FAPAFS details a national regulatory framework for written farming agreements between farmers and sponsors (agri-businesses, processors, wholesalers, exporters, etc.) for sale of farm produce and farm services [4]. Some of its key provisions are:

- The responsibility for compliance of all legal requirements for providing farm services, quality checks, and timely acceptance of farm produce under an agreement rests with the sponsor.

- A farmer cannot enter into such an agreement if it violates the rights of a sharecropper [5].

- Agreements will be applicable for between one crop season to five years, beyond which the parties can decide a mutually acceptable maximum period.

- The agreement will contain a predetermined price for the farm produce, which will be guaranteed in case of any price variation.

- Sponsors cannot acquire ownership rights or make modifications to a farmer’s land under a farming agreement.

There is no denying that these two Acts signal a clear paradigm shift in agri-marketing policies in India, especially at a time when farming has become largely non-remunerative for the large share of population dependent on it and many farmers are opting out of the profession [6].

The FPTC, on one hand, gives farmers a viable alternative to APMC mandis, which have hitherto been the mainstay of the farm to consumer supply chain. Over the years, the APMC system has been criticised for being an inefficient and highly bureaucratised system that has created the state’s monopoly on agricultural marketing. It is also dominated by middlemen and commission agents who control the price and terms of purchase due to which farmers fail to get the true value of their produce while consumers purchase the same commodity at a comparatively higher market price [7]. The FPTC, thus, seeks to bypass the middlemen as well as the numerous fees/cesses applicable to farmers selling their produce in state APMC mandis. Additionally, it provides farmers and buyers access to markets outside their home states and effectively links all regional markets. From the perspective of small and marginal farmers in remote areas who have to rely on middlemen for long-distance transportation, and generally, lack information about any increase in demand in other states, this is a crucial step towards improving accessibility.

In tandem with the FPTC, the FAPAFS brings in a long-awaited regulatory framework for contract farming in India. Until now, such agreements between farmers and agri-businesses have been possible only in states that have amended their APMC acts. The draft Model Contract Farming Act 2018 was also unveiled in this direction but never saw formal legislation. Contract farming is also based around the idea of bypassing the extra costs and quality assurance issues associated with selling to or procuring from APMC mandis and traders [8]. Large Indian retailers such as Reliance and Big Bazaar as well as food processing giants like PepsiCo, Nestle and Hindustan Unilever currently use such models to procure directly from farmers at a mutually agreed price while sometimes providing input services and credit.

More importantly, the two Acts put in place resolution mechanisms in case of disputes arising out of transactions. Under the FPTC, the aggrieved farmers/traders can approach the Sub-divisional Magistrate (SDM) tasked with overseeing the resolution of such cases through a Conciliation Board. Under the FAPAFS, all disputes will first be referred to a Conciliation board as per the provisions of the farming agreement, beyond which the parties can approach an SDM or an Appellate Authority. The order of the SDM and the Appellate Authority, as per both the Acts, has a power equal to that of an order of a Civil Court.

IMPLEMENTATIONAL CHALLENGES

Even though the two Acts aspire to open up India’s agriculture markets to greater competition and better value for farm produce, as with all new policies, the devil lies in the implementation.

The said benefits of an alternative trading mechanism to farmers essentially depend on their willingness to make the shift from a long-established relationship with intermediaries in the APMC system. That shift rests on the availability of certain incentives. Prices offered by traders have to rival the assurance of the Minimum Support Price (MSP) regime that protects farmers from market uncertainties. Farming is laden with various risks from weather patterns to price and demand fluctuations due to which most farmers, particularly smallholders, may not be willing to let go of the safety that MSP provides them. A NITI Aayog study conducted in 14 states covering 1440 farm households found that even though 79% of farmers were dissatisfied with the MSP regime for various reasons, 94% of them wanted it to be continued [9]. This is the case even though the MSP regime has been linked with the shift of cropping patterns in the country towards water-intensive crops like paddy and sugarcane which have led to a serious decline in groundwater over the years [10]. In the long-term, MSP is bound to be a problematic incentive for farmers which will inevitably lead to poor soil quality and decreased productivity. However, nothing at the moment can replace the safety net that it provides.

Another aspect of the two Acts is concerned with the bargaining power of farmers, especially marginal and small farmers holding 86% of the total landholdings in India [11]. The FPTC and the FAPAFS only lay down the rules of engagement between farmers and traders/sponsors. Any “mutually acceptable” terms, particularly under the FAPAFS, are dependent on how well an individual farmer can negotiate. Certainly, there exists a clear bargaining power differential between a smallholder with limited knowledge of market dynamics and a prospective corporate buyer or even a local trader. This differential could be even more pronounced in contract farming considering the number of buyers would be considerably less compared to the number of farmers, creating what is known as an Oligopsony. Such a system would further undermine the ability of a farmer to negotiate a better price or agreement as the buyer would have many other farmers to go to. This lack of bargaining power is already evident under the APMC system where the middlemen have organised themselves better and control the prices through non-transparent methods to pocket profits from periodic price fluctuations [12].

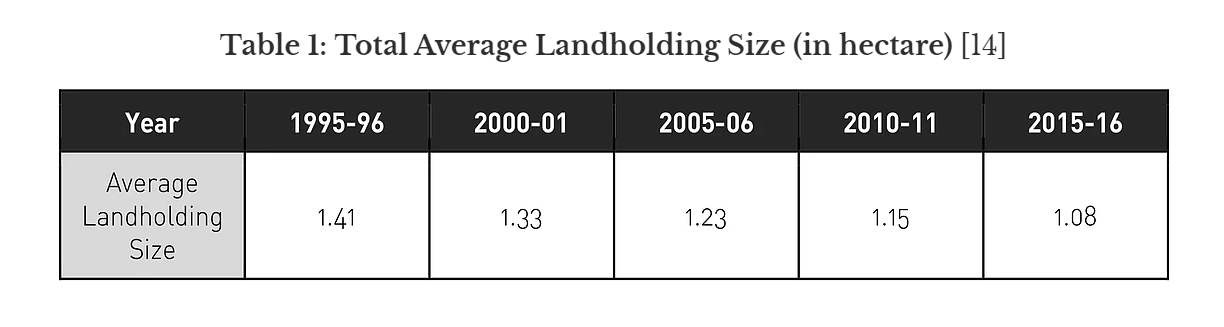

Farmer Producer Organisations (FPOs), registered groups of 100-1000 small farmers that have larger land parcels to work on and collective bargaining power, are essential alternatives in this context. Over the last 25 years, as the average landholding size in India has decreased substantially (table 1 below), indicating continued land fragmentation, FPOs have become more important than ever. Apart from providing farmers collective bargaining power, FPOs also lead to substantial decrease in input and marketing costs. Currently, there are 6000 registered FPOs in the country promoted by various government organisations. However, most of them are in the initial stages of development and encounter issues like inadequate professional management skills, poor resource base, and poor access to credit and infrastructure [13].

Table 1: Total Average Landholding Size (in hectare) [14]

Source – Agricultural Census (various years)

Apart from the above, there are serious issues related to the dispute resolution mechanisms prescribed by the two new Acts. Section 15 of the FPTC and Section 19 of the FAPAFS put the disputes arising out of transactions between farmers and buyers outside the jurisdiction of Civil Courts, keeping them effectively outside the justice system and under the district administration. The sweeping judicial power given to the SDM under the two Acts is concerning, given that local bodies dealing with property registration and land issues are the most prone to corruption as per the India Corruption Survey 2019 [14]. Additionally, Section 13 of the FPTC and Section 18 of the FAPAFS protect the central and state governments, their representatives, as well as the SDM and Appellate Authority from any legal action for anything done in “good faith”. Thus, the Acts give the government representatives including the SDM and Appellate Authority absolute immunity from prosecution. As discussed earlier, there is a substantial power differential between farmers, corporate buyers, traders and local administration officials, which could adversely impact the fairness of the dispute resolution process.

CONCLUSION

The FPTC and the FAPAFS thus entail tangible alternatives for farmers to obtain better prices for their produce. This is particularly true for small and marginal farmers who are overly dependent on middlemen in the APMC system while being stuck with an inefficient MSP regime. However, there are several issues that need acknowledgement and addressal from policymakers if the said benefits of the two Acts are to reach the farmers. Particularly, the farming agreements detailed under FAPAFS will require a reassessment of ground reality. Across states where such agreements are currently allowed, there have been cases of farmers backing off from agreed terms and selling in the market when the market prices are better, and of firms refusing procurement at agreed-upon rates owing to market conditions [15]. In the latter case, the low bargaining power of farmers could be exploited. The promotion and strengthening of FPOs, thus, should be undertaken simultaneously to boost the bargaining powers of smallholders in the face of a changing reality.

ENDNOTES

[1]https://www.ndtv.com/india-news/pm-narendra-modi-says-passing-of-key-farm-bills-in-parliament-watershed-moment-in-history-of-indian-agriculture-2298307 [2]http://164.100.47.219/BillsTexts/LSBillTexts/Asintroduced/113_2020_LS_Eng.pdf [3] As defined under Section 2 of the FPTC Act, any place of production, collection and aggregation including, inter alia, farm gates, factories, warehouses, silos and cold storages. [4]http://164.100.47.219/BillsTexts/LSBillTexts/Asintroduced/112_2020_LS_Eng.pdf [5] As defined in section 3 of the Act, a sharecropper is a tiller who formally or informally agrees to share a portion of total produce or earnings to a landowner. [6]https://www.sprf.in/post/indian-agriculture-the-transition-to-sustainability [7]https://www.sprf.in/post/agricultural-markets-in-india-managing-capital-leakages-in-commodity-linkages [8]http://www.ncap.res.in/contract_%20farming/Resources/1.Introduction.pdf [9]https://niti.gov.in/writereaddata/files/writereaddata/files/document_publication/MSP-report.pdf [10]https://www.indiabudget.gov.in/budget2019-20/economicsurvey/doc/vol2chapter/echap07_vol2.pdf [11]http://agcensus.dacnet.nic.in/NL/natt1table2.aspx [12]https://www.sprf.in/post/agricultural-markets-in-india-managing-capital-leakages-in-commodity-linkages [13]https://www.nabard.org/auth/writereaddata/CareerNotices/2309195308National%20Paper%20on%20FPOs%20-%20Status%20&%20Issues.pdf [14] http://agcensus.dacnet.nic.in/nationalholdingtype.aspx [15] http://www.ncap.res.in/contract_%20farming/Resources/1.Introduction.pdf