Authored by – Sitara Srinivas

Edited by – Kausumi Saha

OVERVIEW

In the context of the rising numbers of COVID-19 cases [1], on March 11, 2020 the Cabinet Secretary of India announced that all states and Union territories should invoke provisions of Section 2 of the Epidemic Diseases Act, 1897 [2]. Rooted in India’s colonial legacy, the Act was passed to tackle the bubonic plague in the then Bombay state, and has remained unchanged since then. In the recent past it has been used often at the district level [3], but the March 11 notification makes it the only known time in the history of independent India that this Act is being seen as a necessary tool for effective health disaster management and risk mitigation at the national level.

The Act has four sections, making it one of the shortest Acts in Indian legislation.

- Section 1 – has the title and extent.

- Section 2 – delegates powers to the State to take special measures and formulate regulations which are to be observed by people to contain the spread of any disease.

- Section 2A additionally delegates powers to the Central Government.

- Section 3 – includes the penalties for violating the regulations made under the Act in accordance with Section 188 of the Indian Penal Code.

- Section 4 – elaborates on the legal protections offered to the implementing authorities [4].

The Act states that at a point where the State Government is satisfied that the state as a whole or a part of it is suffering from, or is being threatened with an outbreak of a specific dangerous epidemic disease and that ordinary provisions of law that are in force are insufficient, it may take, or require, or empower any person to take measures, and prescribes temporary regulations that the public, any person, or any class of person would have to undertake so as to prevent the outbreak or spread of disease. In the context of COVID-19, the government has designated these powers to the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare.

The Act also allows the State Government to take measures and prescribe regulations to inspect people travelling by railways or otherwise and to segregate, in hospitals, temporary accommodations, or other places, those who are suspected by the inspecting officer of being infected by a particular disease.

With the outbreak of the Novel Coronavirus in 2020, the Indian Government announced compulsory quarantine of incoming travellers to the country for at least 14 days from the day of their arrival, and the military has been tasked with setting up multiple quarantining facilities for the same. Additionally, as of noon, 23rd March, the Ministry of Health and Family Welfare reported the screening of 15,17,327 passengers at airports [5].

The Act further grants the Central Government power to take measures and prescribe regulations to inspect any ship or vessel that leaves or arrives in any territories under which the Act extends, and allows for the detention of people who wish to sail or arrive by sail [6].

A person that disobeys any regulation or order made under the Act is punishable under Section 188 of the Indian Penal Code. Additionally, no suit, or any other legal proceedings, can be placed against a person for anything done, or intended to be done, in good faith under the Act [7].

KEY CRITICISMS OF THE ACT IN CONTEMPORARY TIMES

Considering that the Act is over a century old, key criticisms arise from the fact that it fails to account for several factors that shape the nature of epidemics in contemporary times. These include:

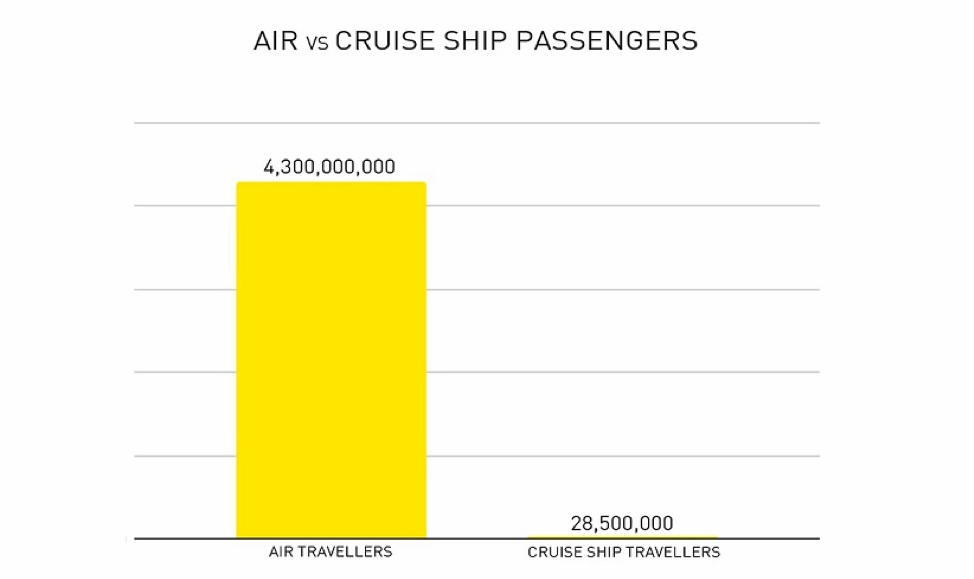

- Increase in the rates of international travel, especially in the context of increased use of air travel in contrast to sea travel: While sea travel was the most prominent mode of travel when this Act was enacted, air travel is now more cost effective and accessible. Today, sea travel is mostly reserved for freight and cruise ships. According to the ICAO, 4.3 billion passengers used scheduled air services in 2018 [8], in comparison to the 28.5 million people who travelled on a cruise ship in the same year [9].

- Evolution of communication mediums like social media and instant messaging: Social media and instant messaging applications like WhatsApp has led to an increase in misinformation and hampered the functioning of governmental agencies. This includes false information about government actions and the efficacy of alternative medical practices, many of which can actually be potentially harmful to health. Some of this false information can be construed as disobeying orders and indirectly creating obstruction and injury, which is punishable under the Act. However, the lack of regulatory mechanisms for this kind of content makes it difficult to trace their origins and to bring creators and distributors to justice.

- Large numbers of inter-state migrations, especially in the context of urban areas: Data inferred from the 2011 Census, for instance, shows that every third person in Delhi and Mumbai is a migrant. High influx of migrants and the generally populous nature of Indian cities means that these cities are often cramped, with one in six urban Indians living in slums. With such a large number of people living in extreme close proximity to one another with lack of alternate housing facilities, many efforts to minimise the spread of contagions, such as social distancing, are bound to fail [10]. The Act does not equip the population to deal with such situations.

- Lack of understanding of modern and contemporary scientific methods of outbreak prevention and response: For instance, while the Act refers to quarantining and detention, it does not look at vaccination, surveillance, and organised public health [11].

- The Act’s ability to deter criminal behaviour: Concerns remain, whether the punishment [12], as defined in Section 3 of the Act, remains an effective deterrent in the contemporary context.

The lack of a definition of what a “dangerous epidemic disease” means remains central to the criticisms of the Epidemic Diseases Act, with Rakesh PS pointing out the lack of specific criteria like the contagion’s magnitude, severity, potential to spread or the section of the population most prone to harm, as one its main drawbacks [13]. Without an understanding of the circumstances that define dangerous diseases, or who has the power to classify a particular disease as dangerous is important since this Act allows for the searching of households, forcible segregation, disinfection, evacuation and humiliation, and use of military powers to ensure proper implementation. The potential for misuse has been echoed by other scholars, including historian David Arnold, who termed it as “the most draconian piece of sanitary legislation adopted in colonial India” [14].

Furthermore, the Act does not have references pertaining to the ethical or human rights principles in the response to an epidemic or how the government can ensure equitable access to healthcare. This includes transparent justifications of governmental action, ensuring access to coronavirus-related information especially for persons with disabilities, people who are illiterate, and those who may not understand the languages used in mainstream media like English and Hindi. With a considerable number of school children dependent on mid-day meals at schools, school shutdowns have impacted their access to food. Several women who have been victims of domestic violence are forced to share close quarters with their abusers, and people who may need essential treatment for pre-existing medical conditions may not be able to receive them with most hospitals being overburdened and several having shut their OPDs, and public transport curtailed. Those with protected attributes, such as trans and HIV positive people, may also feel unsafe in such times. Additionally, there has been a rise in racially-fueled attacks against people – especially those belonging to the North-Eastern states of India [15] [16], or having monolids. A more robust epidemic policy than the one we have currently is required to address a range of such issues.

Among the only legislations that deal directly with the regulation of epidemics in India, the Act is also being criticised for not describing duties or providing clarity to situations in which public rights can be curtailed. The lack of an overarching system that regulates public health measures in an epidemic situation needs to be prioritised in the context of global risks to health, the economy, and several other global institutions. Patro, Tripathy and Kashyap highlight the National Health Bill, 2009 and the Integrated Disease Surveillance Project, among others, as items that can be included in such an overarching framework [17].

Even as other colonial Acts continue to be in use in the country (such as the IPC), epidemics like COVID-19 highlight the need to update both the Act and government health policies, and to invest in the health system in India so as to make it more efficient to manage and mitigate health risks to the country.

ENDNOTES

[1] COVID-19 or Coronavirus disease 2019 is an infectious disease characterised by severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS). The World Health Organisation declared the 2019-20 coronavirus outbreak a pandemic on March 11, 2020. [2] Centre invokes ‘Epidemic Act’ and ‘Disaster Management Act’ to prevent spread of coronavirus [3] Some examples of when the Act has been implemented in recent history include: 2009 in Pune, against the Swine Flu; 2015 in Chandigarh, against Malaria; and 2018 in Vadodara, against Cholera. [4] https://indiacode.nic.in/bitstream/123456789/10469/1/the_epidemic_diseases_act%2C_1897.pdf [5] Ministry of Health and Family Welfare | GOI RSS [6] Section 2A of the Epidemic Diseases Act, 1897. [7] Section 3 and 4 of the Epidemic Diseases Act, 1897. [8] The World of Air Transport in 2018 [9] 28.5 Million People Took a Cruise in 2018 [10] Social distancing involves taking steps to limit the number of people one comes into close contact with. In the case of Covid-19, social distancing has been stated to be one of the ways in which the rapid spread of the virus can be arrested. [11] http://ijme.in/articles/the-epidemic-diseases-act-of-1897-public-health-relevance-in-the-current-scenario/?galley=html#six [12] Under Section 188 of the Indian Penal Code, 1860 there are two main offences: Disobeying an order lawfully promulgated by a public servant, with the disobedience causing obstruction, annoyance and injury to persons who have been lawfully employed, with the penalty for such an offence being imprisonment for a period of 1 month, or a fine of INR 200 or both; and if disobedience causes danger to human life, health, or safety, with the penalty being imprisonment of 6 months, a fine of INR 1000 or both. [13] http://ijme.in/articles/the-epidemic-diseases-act-of-1897-public-health-relevance-in-the-current-scenario/?galley=html#six [14] Science, Technology and Medicine in Colonial India by David Arnold [15] Kiren Rijuju Calls Out Increasing Racist Abuse Against Northeast Indians in Wake of Coronavirus [16] Notably, the North East states saw its first coronavirus case much after the country total crossed the 500 mark. [17] (PDF) Epidemic diseases act 1897, India: Whether sufficient to address the current challenges?Ishanee Sharma looks at Penal Laws for Enforcing Pandemic Protocols here.