In the latter half of the 20th century, production and consumption of goods increased exponentially. The “Global North” [2] was introduced to mass marketing, high consumption, and improved ease of access to products. Consumers began to enjoy the availability of greater varieties of clothing, food, and other consumer goods. With the rise in consumption came a rise in the amount of waste generated. When people in the Global North protested against the creation of landfills in their cities, legislation regarding the dumping of waste became more stringent and naturally, costs escalated. As a solution to this problem, these countries began transporting its waste to countries of the Global South, since the waste management policies there were lax and human resource was cheap as well as readily available. Having found inexpensive ways to process and dispose of their waste, the Global North adopted this system of waste flows—a phenomenon often termed as ‘garbage imperialism’ [3].

Two decades into the 21st Century, these waste flows still exist. The Global South either finds this waste directly dumped on its land, or it recycles or reuses it. A vital example of this is fast-fashion castoffs, which end up becoming fleece or mattress stuffing, or are directly sold in second-hand markets of Asian and African nations [4]. Over the last few years, several nations have begun to ban the import of all or specific types of waste. India, for instance, banned a large amount of waste dumping by passing the Hazardous and Other Wastes (Management and Transboundary Movement) Rules in 2016 and in 2019, strengthened this act by amending it [5]. However, the global shipping industry remains an exception to this, especially with the passing of the Recycling of Ships Act, 2019 [6], which allows for the recycling or dismantling of ships in India.

India, along with other Asian countries like Bangladesh, Pakistan, and China, is a key player in the ship recycling trade. This is specifically because the cheap labour and lax environmental laws, combined with suitable shores make them ideal sites for ship recycling. In India, this industry is centred at Alang-Sosiya in Gujarat.

Shreyasi Pathak, who photographed this series, visited Alang as a part of an academic project at the National Institute of Design, Gandhinagar. Her focus was not just to trace the story of the Exxon Valdez, the much controversial ship that re-catapulted Alang-Sosiya to the global media stage but to also witness the mise en scene of the various shipyards there.

Unlike photographer Edward Burtynsky, whose travel route to Alang was similar to that of some of the ships he photographed, for her, it was a 6-hour bus ride. “The change in the landscape in the last 50-60 kms of my journey to Alang was dramatic. In a matter of minutes, the urban townscapes of Bhavanagar gave way to kilometre-long stretches of shops selling ship items to the ship-breaking yards, and finally, the sea, where one could see rigs and/or ships waiting to be beached in one of the many yards. The land and seascapes reminded me of the photographs that I saw on Facebook and Instagram, of people posing against the massive ships for a selfie with the h

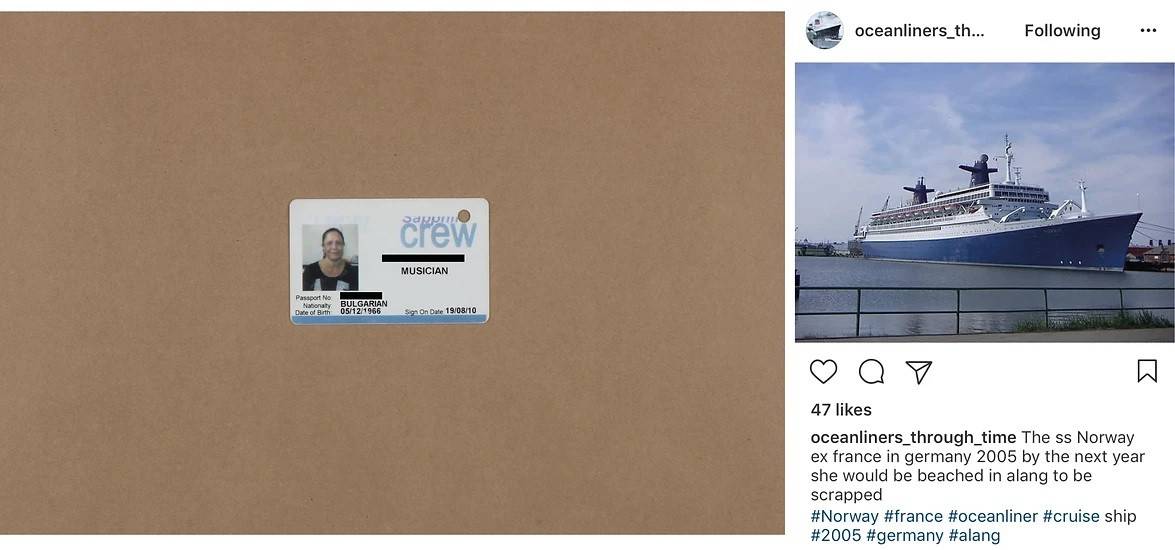

Screenshot

Every year, several ships come to one of the many yards at Alang to get broken down. The most expensive component of a ship, its steel, gets melted down into steel bars and ingots. Other items like furniture, fittings, light industrial tools and crockery are resold. These components represent the many places the ship has been to and the many places its crew called home. For other people, it represents an opportunity to buy a range of “imported products” at cheap prices.

However, the industry has had several negative effects on its workers and the environment. These include the leaking of toxins into the sky, water, and soil, noise pollution, as well as injuries and deaths of several of the migrant workers that work there. These workers often work for less than minimum wage on temporary agreements that they could lose at any time.

In her words, “One is confronted with the visually arresting landscapes and the monumentality of the broken ships that, for a split second, foreshadowed the humanitarian and the environmental crisis that one often allied such industries with. Such manufactured landscapes [8] may appeal to one’s imaginations of an apocalyptic town, a (possible?) reality in the third world. Which also becomes a shopping heaven if one just retraces their steps by two kilometres”.

To quote Allan Sekula, “the Ark is no longer a bestiary but an encyclopaedia of trade and industry” [9]. Even as a dead vessel, a ship is the bearer of wealth, goods, and livelihoods to many. Expressing this, Pathak says, “[A] ship that’s about to be beached or is newly beached goes through Hindu rituals associated with welcoming something that brings prosperity and wealth to home or business. A ritualistic celebration is followed where sweets are distributed to everyone present and the crew is bid goodbye. Friends and family of the shipowner get to visit the ship to keep whatever they may find inside.”

At the same time, the question remains: who benefits from the industry? Is it the Global North, that has found a cheap way to dispose of its waste? Is it the Gujarat Maritime Board and the shipyard owners who see their profits increase year on year? Or is it the workers, who find employment which is hard to come by? Additionally, the more important question is, at whose cost is this benefit? Is it at the cost of the villages of Alang-Sosiya and Bhavnagar, who now deal with pollution and several health issues, and the workers who inhale toxins and face death and life-threatening injuries? Alang-Sosiya today has many identities: a tourist destination where one can visit the carcasses of dying ships, a shopping destination to buy what comes out of the ships, and also a repository (in flux?) of a first-world luxury ship dump.