Fatima Begum*, a homemaker, was relieved when the Foreigners Tribunal in Ulubari in the Kamrup district of Assam validated her claims of being an Indian citizen in July 2018. However, her respite was short-lived for she soon received a notice to appear before the Foreigners Tribunal in Kamrup (rural). Her nationality was questioned again, and she had to go through more interrogation and scrutiny. Despite providing all the previously accepted documents like the voters’ lists of 1966 and 1970, a bank identity card and a name correction affidavit (for her father’s name), the Tribunal discovered a minor discrepancy in her mother’s name. This led to the nullification of her claims about her nationality, and Fatima was declared a foreigner.

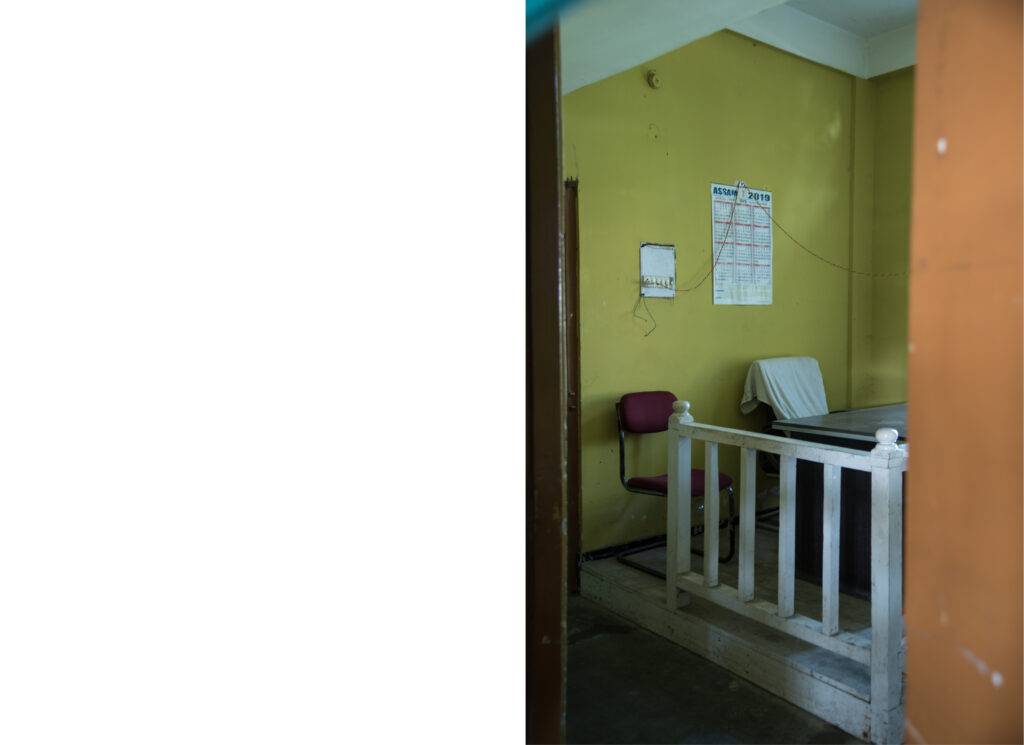

A Foreigners Tribunal is a quasi-judicial body established under the Foreigners (Tribunal) Order, 1964, which aims to determine if a person staying illegally in India is a foreigner or otherwise. In 2019, the 1964 order was amended to provide the District Magistrates in all States and Union Territories the power to constitute tribunals, something that only the Centre was authorised to implement earlier [2]. At present, Assam has more than 100 functional Foreigners Tribunals with an additional 1000 sanctioned by the Ministry of Home Affairs in mid-2019.

The National Register of Citizens (NRC) is one of the channels through which the Foreigners Tribunals receive cases of people suspected to be illegal immigrants. When a person doesn’t find their name in the NRC, they are required to approach these Foreigners Tribunals and prove their citizenship, just like Fatima Begum. According to the amended 2019 Order, if unsatisfied by the ruling of the Tribunal, a person may appeal to the High Court, provided that their case is believed to have adequate ‘merit’. The Order, however, does not provide any guidelines as to the nature of this ‘merit’, and thus provides the Tribunals with unrestricted power in determining a person’s citizenship.

In 2015, Bishaka Bala Das was abruptly taken away from her home in Bijni, Chirang District to the Kokrajhar District Jail. Bishaka used to clean houses to sustain her family’s livelihood and was completely unaware of the legal consequences of the notices she received from the Foreigners Tribunal that demanded her presence in court. An ex-parte order [3] by the Foreigners Tribunal in Bongaigaon declared her a foreigner based on her absence from about 37 court hearings that pertained to her case. Despite presenting legitimate documents, including the voters’ lists of 1966 and 1970 in her father’s name, the Gauhati High Court dismissed her plea owing to her “neglectful” manner in advocating her claims. She has since been detained, and her release is dependent on the presentation of bonds with two sureties of INR 1,00,000 each. These unfavourable circumstances have plunged her family into a financial crisis.

Fatima Begum and Bishaka Bala Das lost their citizenship in a country where a large portion of the population is illiterate, and registration of births was not common until recently. Their cases also highlight the violation of the principle of res judicata (“a matter that has been adjudicated by a competent court and therefore may not be pursued further by the same parties”) [4]. Essentially, as part of the verdict on Abdul Kuddus v. Union of India in 2019, the Supreme Court had stated that once a Foreigners Tribunal had declared a person to be an Indian citizen, the same, or even a different, Foreigners Tribunal could not declare the same person to be a foreigner after a couple of years. However, both Fatima and Bishaka had their citizenship challenged by the Foreigners Tribunal even after being declared an Indian citizen earlier. They, and many others, have had to undergo gruelling experiences to argue their nationalities repeatedly until the Foreigners Tribunal found expendable reasons to dismiss their claims altogether.

The problems inherent in the functioning of Foreigners Tribunals are apparent from these case studies. Minor anomalies are taken as definitive grounds to dismiss a person’s citizenship status without taking into account the contextual hardships of the unlisted. Moreover, the customs associated with marriage in India make it extremely difficult to trace the familial ancestry of women, thus making them much more vulnerable to the scrutiny of a Tribunal. These unaddressed issues hold major humanitarian concerns in the context of the NRC process in Assam if corrective and preventative measures aren’t adopted to manage them.