Gujjar or Van Gujjar and Bakkarwal communities are nomadic shepherding tribes residing in the Himalayan regions shared between India and Pakistan. In India, they primarily live in Uttarakhand, Himachal, and Jammu and Kashmir. Gujjars and Bakkarwals migrate with their livestock biannually. At the onset of summers, they migrate from lower altitude villages (gran) to highlands (dhok) and make the return journey at the beginning of winters. This migration is an old tradition that sustains pastures for their livestock and helps them escape the heat of low altitude villages in summers and the cold of high-altitude lands in winters. The two tribes are differentiated by the animals they keep – Gujjars primarily rear buffalos and Bakkarwals rear sheep and goats.

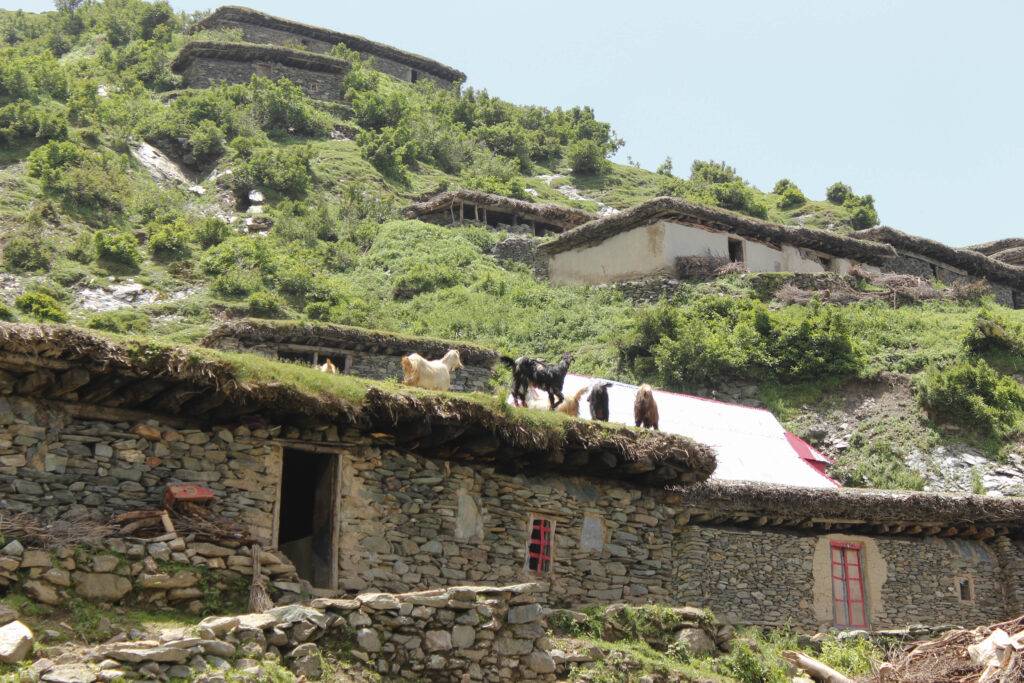

The Gujjars of Surankote in Jammu and Kashmir traditionally dwell along the Pir Panchal mountain range, near the Indo-Pak Line of Control (LOC). Many of them have homes in villages where they stay in winters and grow crops throughout the year. Their houses usually comprise small units with many such blocks placed organically in the terrain working together as a unit. The livestock occupies the lower floor, and the family stays on the upper floor. All the spaces inside the houses are multi-purpose. One key area is the cooking space where food is cooked, served, and the family spend time together. They sometimes even sleep there as it is relatively warmer. These traditional houses, now called kutcha houses, are made of clay, shrubs, branches, and timber. The clay of suitable properties is collected from the village, and the timber is procured from the forest or is reused from old constructions. Dead trees from forests or non-endangered trees from the local property can be axed after acquiring permissions from the government.

Over the last decade, the community and the region have seen a drastic culture change. The community is shedding its traditional practices at an unprecedented rate. Amongst other changes, it is embracing new construction materials and techniques as a result of a prevalent aspiration in the community to have pukka houses (made of reinforced cement concrete and bricks). Locals associate pukka houses with ‘growth’ and ‘development’. Moreover, living in pukka homes saves the residents time and effort as the house does not require rigorous maintenance, and is more resistant to forces of nature like rains, snow and storms, as well as insects and pests.

The shift from kutcha to pukka is more pronounced in areas that are accessible by road. These areas have relatively more contact with the cities and have access to material like concrete and GI sheets. Most of the new roads were made by local contractors under Pradhan Mantri Gram Sadak Yojna (PMGSY), connecting sporadically spread villages. Moreover, an incentive to make a pukka house is provided by Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojana (PMAY). PMGSY, coupled with PMAY, has accelerated the transition to pukka houses.

Pukka houses are made of RCC, bricks, iron, and GI sheets. Brickwork has supplanted mud walls, and RCC slabs and GI sheets have replaced traditional mud, shrub and timber roofs. These new houses can typically be classified into two broad kinds – one with RCC roofing that is locally called ‘pukka makaan’ and the other with GI roofing referred to as ‘bungalow’. The RCC-roofed houses are less suitable for the local climate as they become too hot during the summer and too cold during the winter. Many locals, especially the older generation, complain that they cannot sleep in the “pakka makaan”.

Traditional houses of the Gujjar community, now often dismissed as the ‘kutcha’ house, are better equipped to respond to the local climate. They also do not have any long-term impact on the environment. They can be made and disassembled easily, and the material can be upcycled multiple times. Therefore, while embracing these modern materials and methods has its advantages, it does come at the cost of losing out on sustainable, and often practical, traditional practices.