Author: Archana Sharma

River Gandak, also known as the Kali Gandaki or Narayani, originates near the Tibet-Nepal border and enters Nepal from the Mustang region. After traversing through the lands of Nepal, it crosses the Indo-Nepal Border at Triveni Dham and reaches Valmiki Nagar in Bihar. From Valmiki Nagar, the Gandak winds its way through the states of Uttar Pradesh and Bihar before merging into the Ganga at Hajipur and Sonepur (Singh, 2018). This river is home to several endangered species which thrive extremely well in its ecosystem; it includes ghariyals, gangetic dolphins, turtles, and magar (Choudhary, 2009-10). While several mythological stories have been related to the Gandak, which gives the river a sacred significance, it also has historical significance due to the settlements that have evolved on its bank or in its vicinity. The river and these settlements tell a different story of Northern Bihar, a story that is not widely known in the bigger circles.

Part 1: Journey of the Gandak River from Origin to Confluence

Named as Kondochates by Greek geographers

I have been identified as the ever-flowing river of epics

They say that I travel through three different countries

But my course has not known any boundaries

I identify myself with mountains, gorges, and plains

As they are the highlights of my journey

Before I reach my final destination

Owing to the relatively unchanged nature of the ecosystem

Gangetic dolphins, turtles, ghariyals, magar, and mahseer

Have always been companions in my journey

Association with the stories of different faith

Has given me a sacred status

The name Narayani is owed to the presence of ammonite fossils

Also known as shaligram,

the fossils are venerated as Hindu god Vishnu or Narayan

Puranic legends of Gaj-Grah and travels of Buddhist Guru Rinpoche

Have linked me to the two oldest religions of the world

Originating from the snowy mountains of Mustang

I travel southwards through the gorges of Dhaulagiri, Manaslu, and Annapurna

My entrance to Indian sub-continent is at Triveni Dham

It is here that I am renamed as Gandaki or Gandak

It is here where the story of Gaj-Grah starts

It is here when I finally escape the narrow gorges of mountains

And spread my banks to see the plains of Bihar and Uttar Pradesh

It is here that I am welcomed by rivers of Sumeshwar Hills

Panchnad and Sonaha, as they accompany me in rest of the journey

After Triveni, I pass through Valmiki Nagar

Or as it was called originally, Bhainsalotan

the village known for its tiger reserve

is also linked with stories of Rishi Valmiki

Said to be the original site of Valmiki Ashram

The forest around the village has ruins of an old temple

Leaving the last views of mountains of Nepal

I move forward to explore the plains

In the plains I catch a glimpse of Burhi Gandak

A part of me that was left behind thousands of years ago

When I decided to shift my course westwards

Although the current scenery for the rest of the journey is almost the same

With small towns and agricultural lands lining my banks

There once was a time when my banks were adorned with mango groves

I have always been fascinated by the transient nature of humans

For it has resulted in wonderful creations

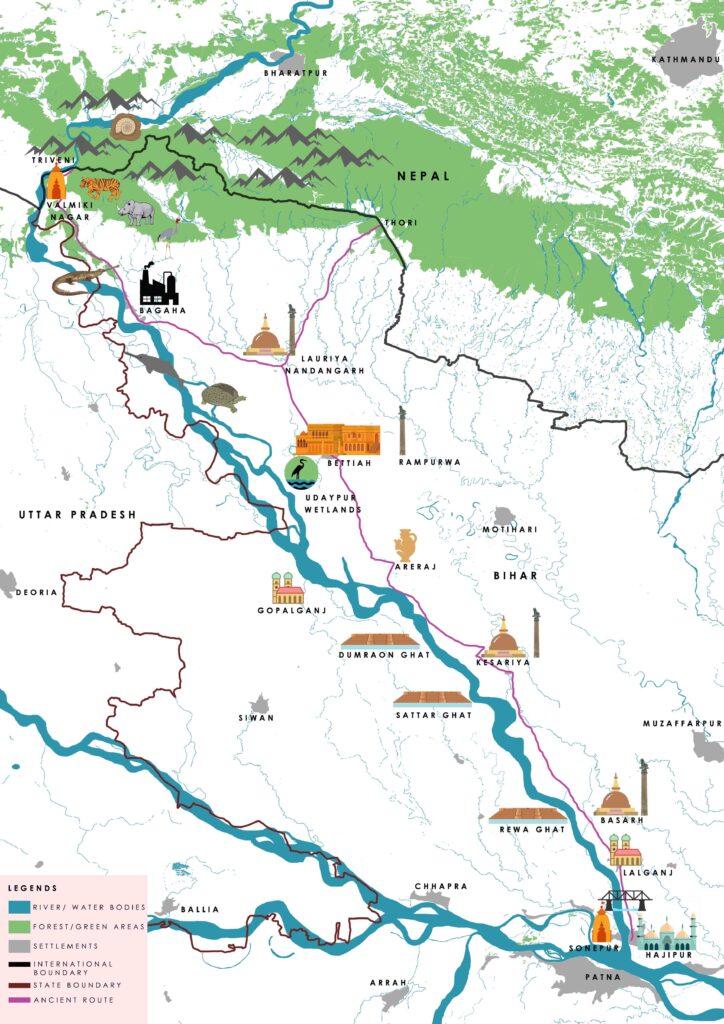

One such wonder is the land route developed in the plains of Bihar

A route parallel to my course

A route facilitated by my waters and abundant groves

A route that connected capitals of Vriji Republic and Magadha

To the mountainous region of Nepal

A route which was turned into Imperial highway by Ashoka

A route that is lined with Ashokan Pillars and Buddhist Stupas

Mainly at Basarh, Kesariya, Areraj, Lauriya Nandangarh

But the one at Rampurva has found its home

At a place where President of India resides

I pass through the historical industrial town of Bagaha

But I only catch a glimpse of Bettiah

The home and capital of Bettiah Raj

Down south I cross some ghats in the region of Saran

Ghats that were developed to facilitate river trade

Ghats that were named as Rewa Ghat and Satter Ghat

Finally, I reach to the twin towns of Hajipur and Sonepur

A region that is known as Harihar-kshetra

A region where story of Gaj-Grah ends

A region that was developed to facilitate trade with Patna

A region where at last I meet Ganga

To accompany her on her journey

A journey that ends into the abyss of Bay of Bengal

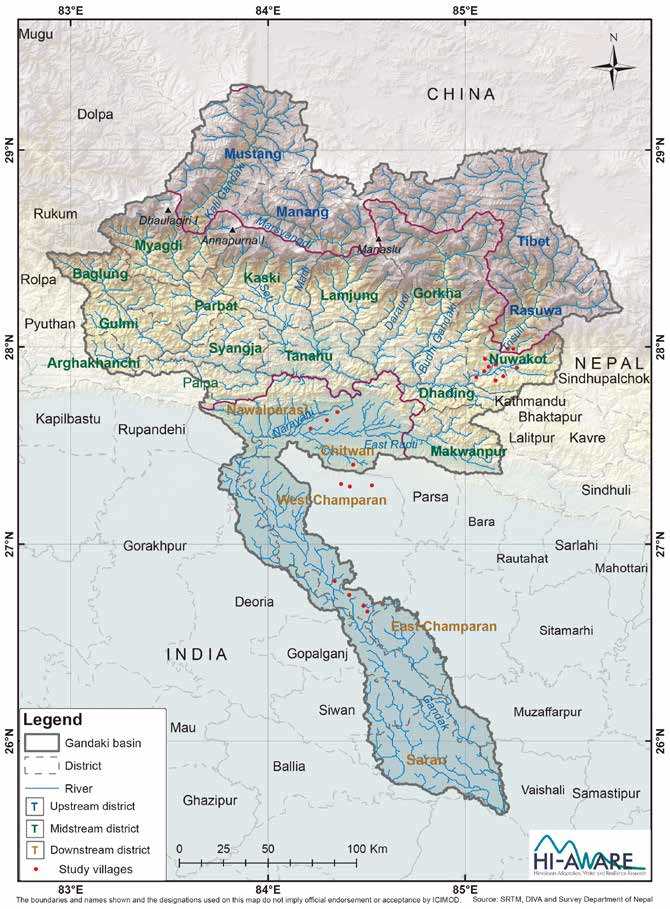

Figure 1. Basin of Gandak River; Source – The Gandaki Basin – Maintaining Livelihoods in the Face of Landslides, Floods, and Drought (Working Paper 9)

Part 2: Understanding the Relationship of Cultural Heritage with the Riverscape

Bihar is divided into two parts by the Ganga, i.e., North Bihar and South Bihar. While South Bihar is bounded by Jharkhand and West Bengal on the southern and eastern side, North Bihar shares an international boundary with Nepal. Due to its location near the foothills of mountains of Nepal, North Bihar has an elaborate river system which comprises the Gandak, Kosi, and Ghaghra among others.

Gandak, like every other river and water resource in the world, has been the source of ecological sustenance. It also holds great cultural and sacred significance and has inspired many cultural heritage sites located along its banks. To understand the evolving relationship of cultural heritage sites with respect to the riverscape, an in-depth analysis is required wherein the heritage sites need to be studied in the context of the concerned settlement and their location along the river. For this purpose, three settlements have been chosen, which are Valmiki Nagar, Hajipur, and Sonepur. These settlements are not just different in terms of settlement hierarchy, topography, nature of heritage sites, and nature of interventions undertaken, but also because of their location along the river. Valmiki Nagar, the first settlement, is located at the Indo-Nepal border, the point where the Gandak enters the country, while Hajipur and Sonepur are located at the point of confluence.

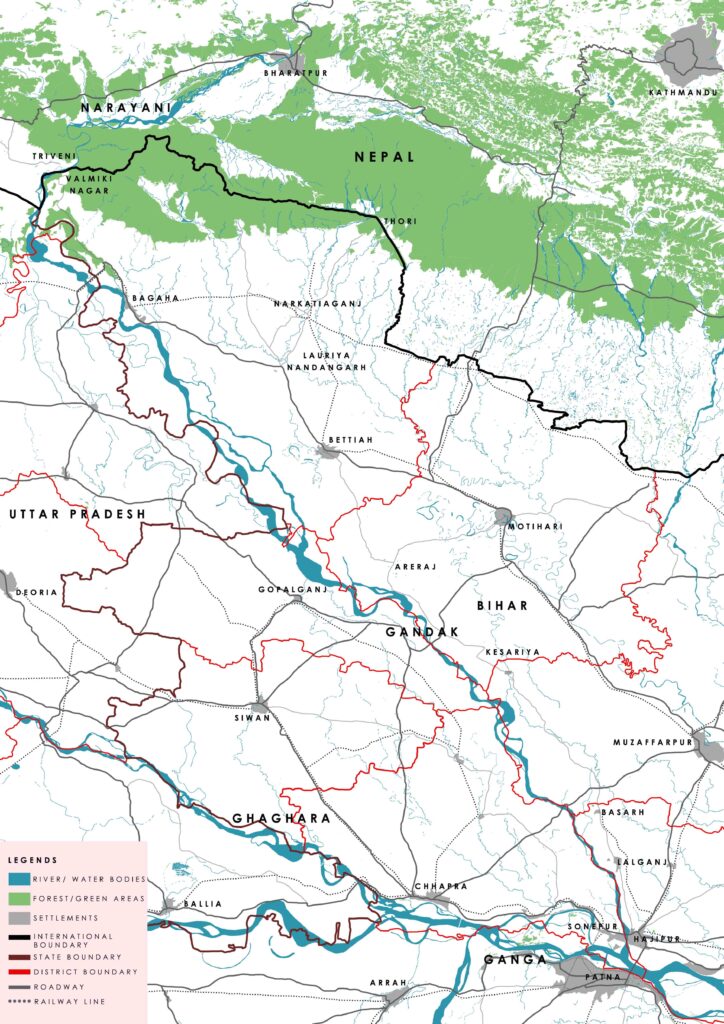

Figure 2. Map of Northern Bihar and Southern Nepal showing state boundaries, district boundaries, major roadways, and railway lines

Figure 3. Illustrative map of the course of Gandak River showing historic sites and settlements and other major characteristics of the river

Ecological Significance of the River

The ecological hotspots of the Chitwan National Park area of Nepal, Valmiki Tiger Reserve of India, and the fertile plains of parts of northern Bihar and eastern Uttar Pradesh, are owed to the flow of the Gandak River in this region. It is evident that the presence of the Gandak and its tributaries in the Terai region has led to huge natural reserves of forest in Nepal and India. These forests are home to many wildlife and avian species such as tigers, leopards, rhinoceros, gaurs etc. The river itself is an ecological reserve, as it is home to many endangered species such as gangetic dolphins, turtles, ghariyals, magar, and mahseer. The presence of ecologically rich areas, along with a constant source of water, further enabled the establishment of human settlements in these areas.

Apart from the Terai region, the river has also played an important part in shaping the ecological diversity of northern Bihar and eastern Uttar Pradesh. The fertile plains were once filled with groves of mango and banana trees owing to the quality of soil and abundance of water (Chaudhury, 1962). While most of these groves have been replaced with farmlands, the river has played an equally important role in enhancing the agricultural capacity of these areas.

Valmiki Nagar, or the Village of Bhainsalotan

Valmiki Nagar, known for its tiger reserve, is connected with Chitwan National Park of Nepal, and the region is known as a biodiversity hotspot. This is the point where Gandak finally leaves the narrow gorges and sandstone mountain range of Sumeshwar (located at Indo-Nepal border) to begin its journey on the plains of Bihar and Uttar Pradesh.

Originally known as Bhainsalotan, Valmiki Nagar is renowned as the mythological site where the ashram of Rishi Valmiki was situated. Valmiki, the author of Ramayana, is said to have given shelter to Sita in his ashram when she was exiled by Raja Ram. Located at the border of India and Nepal, the village is close to Triveni Dham – the place where Rivers Panchnad and Sonaha merge into Gandak. These rivers originate in the Sumeshwar Hills of Nepal and are considered sacred as well due to their association with Gandak. It is at Triveni Dham that the most important story associated with the river starts.

It is said that at Triveni Dham, a fight broke out between the lords of forest and water, i.e., the Gaj and Garah, the elephant and the crocodile. Reference to this story is found in Srimat Bhagvada Gita, which narrates that one day a huge elephant came with his herd to bathe in the river (Chaudhary, 1962). It was the place where the lord of water or the crocodile lived. Seeing the elephant, he caught him by the leg and tried to drag him into deeper water. This struggle continued for thousands of years, when at last, the elephant started praying to Lord Vishnu or Hari. His prayer was heard, and Hari saved him from the grip of the crocodile, in the presence of other gods. While the fight started at Triveni, due to the flow of Gandak, it ended at Harihar-kshetra (presently near Hajipur and Sonepur) – the place where Hari had appeared (Chaudhary, 1962). Owing to the sacred nature of this place, various cultural heritage sites are located here, including Valmiki Ashram, Jata Shankar Mandir, Kaleshwar Mandir, and Nar Devi Mandir.

Valmiki Nagar of today was shaped in the early 1900s, when the Gandak Project was approved between Nepal and British India. With the construction of barrage and canals, the place also witnessed the erection of bungalows and staff quarters. Most of these are still intact, while remnants of others can still be seen in the village.

Harihar-kshetra – The Twin Towns of Hajipur and Sonepur

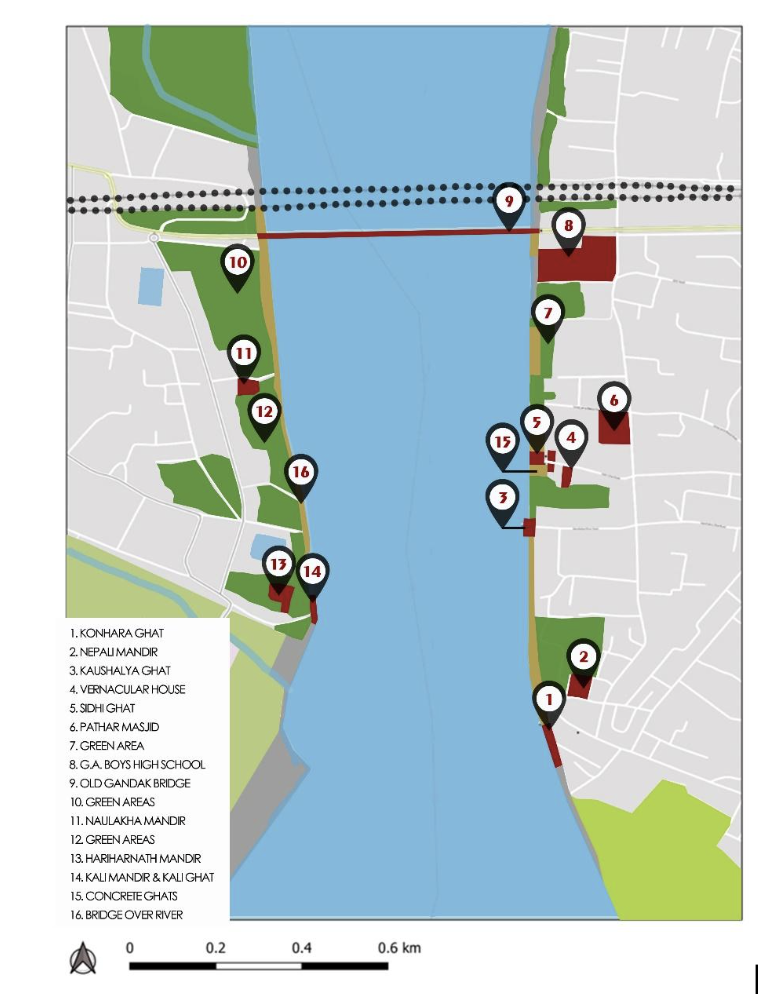

From Valmiki Nagar, the Gandak travels southwards, and after crossing many towns and settlements, it reaches Harihar-kshetra. Today, the region of Harihar-kshetra is synonymous with the twin towns of Hajipur and Sonepur. The towns are situated across the historic city of Patna and at the confluence of Gandak with Ganga. Owing to the location, this region has benefitted in several ways such as travels of saints and scholars, trade and travel, cultural exchange etc. Hajipur is believed to be the seat of sages or rishis of ancient times (Chaudhury, 1962). It was traversed by Ram and Lakshman while they were on their way to Mithila, and was also visited by Lord Buddha whenever he was in Vaishali (presently the village of Basarh). Hajipur as a town was established between 1345 AD to 1358 AD on the eastern bank of the Gandak by Haji Ilyas or Shamshuddin Ilyas, the king of Bengal. He built an elaborate fort on the bank of Gandak, ramparts of which were visible until a few years ago. However, the mosque, or Pathar Masjid, of the fort is still standing tall. Locals say that in the 17th and 18th century, several ghats and temples were constructed along the river, but most of them were laid to waste in the massive earthquake of 1934. Some of them have still survived today, like the Nepali Mandir, Hajuri Math, and Sidhi Ghat.

Like Hajipur, the town of Sonepur also has temples situated along the bank of river and constructed in the same time period. In British India, several social and utilitarian infrastructure were developed in both these towns. Bridges connecting the two towns were built on the Gandak, which included a railway bridge as well. In the case of Hajipur, a school, several bungalows, a racecourse, and dance club were constructed along the river, but due to change in the course of the river, everything except the school was destroyed in 1837 (Chaudhury, 1962). Learning from their mistake, the British officials conducted the next bout of construction of bungalows, dance club, and other infrastructure in Sonepur, and away from the river.

Figure 4. Map of Gandak River along the town of Hajipur and Sonepur showing cultural heritage sites of the town