Introduction

The landmark case of People’s Union of Civil Liberties (PUCL) Vs The Union of India 2003, was the turning point for transparency with regards to elections, as it made it mandatory for contesting candidates to declare their criminal records in their affidavits accessible to the public. Quoted by P.V Reddi in his judgement from the State of U.P Vs Narain 1975 case, and aptly so: “In a Government of responsibility like ours, where all the agents of the public must be responsible for their conduct, there can be but few secrets. The people of this country have a right to know every public act, everything that is done in a public way, by their public functionaries.”

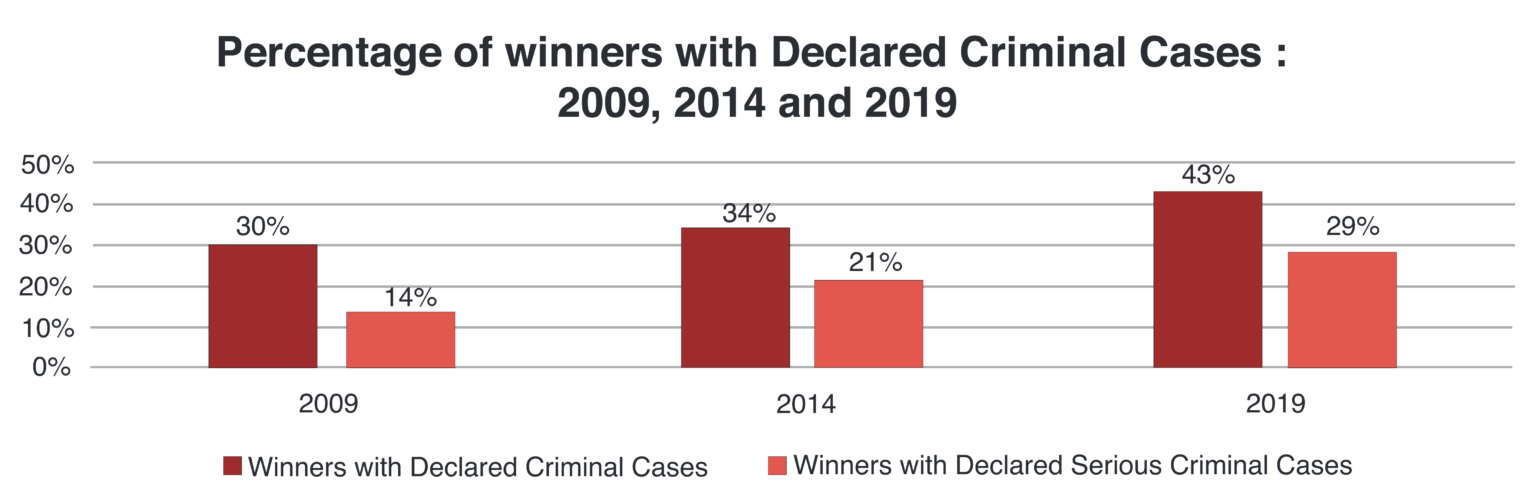

On the basis of these founding principles, we have public access to the criminal records of candidates. Transparency should inspire a more responsible selection of candidates in the legislature; however, this seemingly hasn’t been the case, with an upward trend in the amount of the Members of Parliament being associated with criminal cases. In the past three elections, the number of Lok Sabha members with a criminal charge to their name has consistently increased, according to a report published by the Association of Democratic Reforms (ADR). The report also differentiates between the overall criminal charges filed and the serious criminal charges levied against politicians. The criteria for “serious criminal charges” set by the ADR are as follows:

- Offence for which maximum punishment is of 5 years or more

- If an offence is non-bailable

- If it is an electoral offence (for eg. IPC 171E or bribery)

- Offence related to loss to exchequer

- Offences that are assault, murder, kidnap, rape related

- Offences that are mentioned in Representation of the People Act (Section 8)

- Offences under Prevention of Corruption Act

- Crimes against women.

Between 2009 and 2019, there was a worrying increase in the number of Indian Members of Parliament (MPs) involved in criminal proceedings. Of the 543 Members of Parliament polled in 2009, 162 were dealing with criminal accusations, and 76 had serious charges against them. In 2014 after a survey of 542 MPs, the number facing criminal charges rose to 185, of which 112 were serious charges. This increased trend continued in 2019, when 159 MPs were facing serious criminal charges, and 233 out of 539 MPs surveyed reported dealing with criminal allegations.

Figure 1. Percentage of winners with Declared Criminal Cases 2009, 2014, 2019

Source: Association for Democratic Reforms

Relevance of the Criminal Records

In the PUCL Vs Union of India 2003 judgement, the expression of the right to vote is formulated under two tenets, i.e the formulation of opinion about the candidates and the expression of choice as casting a vote in the favour of the candidate preferred. These two tenets are complementary to each other, and upholding both becomes essential to preserving the spirit of democratic polity. The formulation of opinion about the candidate is first and foremost made complete by providing all relevant information about their history that will become relevant in the public debate surrounding the candidate’s character. Thus, in his judgement, Venkatarama Reddi followed this line of rationale to explain the relevance of revealing these records to the public eye. In the context of this foundational argument, we will analyse the various impacts that candidates have on the electoral playground and their effects on institutions and developmental progress.

While the judgement comes from the standpoint of defending the right to vote, the concerns around the growing criminality within legislative chambers had been brewing under a different context. The origins of this concern can be traced back to the Vohra Committee Report in 1993, which was created as a response to the growing concerns about the nexus of politicians and bureaucrats with the underworld and mafia, particularly in response to the infamous activities of the Memon Brothers and Dawood Ibrahim, the prime culprits of the Mumbai 1993 bombings. The report, although primarily created as a response to the growing influence of the crime syndicate in Bombay, noted the same structures of powers in other parts of the country as well. Gangs affiliated with politics in Bihar, UP and Haryana, and narco-terrorism networks in the states of J&K, Punjab, Gujarat and Maharashtra were highlighted in the pages released to the public. The report highlights the real dangers of criminal affiliations primarily in the context of the control that criminal organisations can gain over the functioning of the state.

Additionally, the Second Administrative Reforms Commission (ARC) that was constituted in 2005 also refers to the Vohra Committee Report, noting the proliferation of large-scale economic crimes that involve politicians and bureaucrats. The ARC also recommended the disqualification of candidates with serious criminal charges and charges of corruption. The Vohra Committee Report and the ARC report can contextualise the demand for inquiries into the criminal records of candidates and subsequent actions on the same; these criminal charges pose a wider threat than just ethical considerations.

According to a study by Tiwari & Golden (2011), candidates who have self-reported criminal backgrounds tend to be more prevalent on election ballots in India’s constituencies where there are higher numbers of illiterate voters and when political parties are facing intense competition.

Additionally, it also makes the point that the presence of such candidates tends to decrease voter turnout, which supports the theory that acknowledged criminals use intimidation tactics to dissuade opposition supporters from voting. A study done over 2004 and 2009 elections, points to the potential subversion of fair electoral practice that may be observed in the case of candidates with criminal records running in the elections.

Pehl (2015) argues that the entry of “tainted”, i.e. candidates with criminal records, may also be a trickle-up effect of the increased proliferation of state legislators with criminal antecedents, and additionally their status within the grand framework of national political parties. These legislators also hold notable influence within their states as well; Kim & Lee (2022) examine how state-level legislators with criminal records influence the police institutions, especially in states with low development and high illiteracy rates, and manipulate police effectiveness and the rate of investigations take a significant dip. Prakash, Rockmore & Uppal (2014) observed a significant negative impact on economic activity in constituencies where state-level candidates with criminal records were elected, with growth rates in Indian states decreasing between 2.7% and 7.6% The connection between these state-level legislators and the members of Parliament should thus be considered in depth, noting how the state-level actors are also important as political figures for the national parties.

State legislators with criminal records become more detrimental to local consequences than a member of parliament would effectively be; however, it may be argued that the core issue is the lack of redressal when it comes to the pendency of these criminal cases. The ongoing neglect of these unresolved cases, even after a decade or more, highlights a fundamental issue in Indian law and politics: a lack of recognition for signals indicating dangerous character flaws within our legislative representatives.

Institutional Involvement

The courts have been the foremost authority in bringing about regulatory obligations for political parties to focus their efforts on publicising the criminal antecedents of candidates in the Parliament and state legislature. From the judgement that started the practice of declaration in 2003, there have been several cases filed in the name of public interest to address the growing issue of increasing candidates with criminal records in the Parliament, with a consistent upward trend shown in the amount of cases declared.

According to section 8 of the Representation of People Act, 1951, only candidates who have been convicted of criminal charges can be disqualified from their title as a Member of Parliament or Legislative Assembly.

Calling for the debarment of candidates has been observed in the Manoj Narula vs Union of India case that was filed in 2005, and consequently decided in August 2014. The court here has refrained from debarring candidates who are involved in serious or heinous cases on account of their inability to impose a disqualification criteria as per their jurisdiction. While the court refuses to comment on the same in consequent judgements related to criminal antecedents for political candidates, it has issued an order in March 2014 to expedite cases of these nature on an urgent basis, specifically within one year of the date they are charged. According to data from an affidavit issued by the Centre in response to Supreme Court proceedings in 2018, the conviction rate for MPs and MLAs combined stands at 6% (Raman, 2018), with only 38 of these politicians actually facing the six-year ban from contesting elections as mandated in the Representation of People Act.

As of February 2020, subsequent to a contempt petition from the Supreme Court following the judgement in the Public Interest Foundation and Or. v Union of India and Anr. case in 2019 (Tripathi, 2020), political parties are mandated to disclose detailed profiles of candidates with ongoing criminal proceedings promptly. Such disclosure encompasses the delineation of charges, the status of legal proceedings, and relevant judicial particulars. It must be noted that under Section 125A of the Representation of People Act, a candidate who falsifies or conceals information regarding pending criminal cases is liable to a fine and six months in prison but not disqualification (Pavithra K M, 2020). This points to a loophole that political parties may or may be already exploiting, as there is no considerable consequence to manipulation in the publication of their criminal records.

Additionally, parties are obligated to provide justifications for selecting candidates with criminal records, emphasising their qualifications rather than mere electoral prospects. Non-compliance with these directives results in primarily legal repercussions in the form of proceedings in the court. However, the consequences of this additional obligation have been lacklustre regarding what it sets out to do. In the Telangana state assembly elections for example, no reasons were provided for 45% of candidates holding pending criminal cases (Reddy, 2024). Additionally, the reasons that were cited for criminal candidates were much along generalised lines, which don’t offer much explanation (Roopi, 2023)

Notably, the Supreme Court also underscores the importance of ensuring accessibility to crucial information, mandating the dissemination of information related to criminal records through party websites and social media as well, adding to the earlier requirements of posting it through a vernacular and a national newspaper. These regulatory measures aim to foster transparency and accountability in the electoral process, although the primary source of intervention in matters related to criminality, as observed through the history of reforms, has been the Supreme Court with the Election Commission acting as the executioner of these reforms.

Disbarment of Candidates from Elections

The first step with regard to the criminality problem is the disbarment of candidates entirely from the election on the basis of criminal charges of serious offences. This is the minimum bar that needs to be established in order to address the issue highlighted in this article. This has been brought to light through the Manoj Narula vs Union of India case, as mentioned above. The court suggested the following amendment to the Representation of People’s Act, 1951:

Disqualification on framing of charge for certain offences. – (1) A person against whom a charge has been framed by a competent court for an offence punishable by at least five years imprisonment shall be disqualified from the date of framing the charge for a period of six years, or till the date of quashing of charge or acquittal, whichever is earlier.

It must be noted that the Vohra Committee Report and the Proposed Electoral Reforms Report by the ECI make the same recommendations for the amendment of the disqualification criteria, which highlight the fact that the main reservation against this amendment is coming from the legislature itself on account of the current high criminal allegations within the members of the Parliament. A stronger push for electoral reforms is required, and external pressure from the Supreme Court in this regard would be essential.

Conclusion

The rising trend of Lok Sabha members with criminal records presents a multifaceted challenge to the democratic fabric of India. Despite landmark judicial interventions mandating transparency in candidate disclosures and calls for electoral reforms, the problem has persisted and even escalated. The implications of this trend extend beyond mere ethical considerations; they strike at the heart of democratic principles, affecting voter confidence, electoral fairness, and governance effectiveness.

The foundational argument laid out in the PUCL Vs Union of India 2003 case emphasises the public’s right to know about the criminal backgrounds of candidates to make informed electoral choices. However, the escalating numbers of MPs embroiled in criminal proceedings reflect a disconcerting reality. Despite the institutional involvement of the courts and regulatory measures, such as mandatory candidate disclosures and expedited legal proceedings, the conviction rate remains alarmingly low.

The proceedings of these cases have been painstakingly slow, which falls in line with the general pace with regard to criminal proceedings in the country, with over 30% of criminal cases being pending for five years or more. However, the importance of these particular proceedings holds particular significance in the fact that they indirectly may determine the legislators of the country, and whether they stand fit to govern the state. It is this context that makes the settlement of these cases all the more important.