Authored by: Ankita Tripathi

Edited by: Riya Singh Rathore and Avishi Gupta

INTRODUCTION

In September 2021, the Union government launched a new Production Linked Incentive [PLI] Scheme to boost the manufacture of man-made fibres [MMF] in India. The PLI scheme will offer incentives from the financial year [FY] 2025 to 2030. MMF are different from natural fibres such as cotton, silk, and jute. They are produced from crude oil to form synthetic fibres and wood pulp to form cellulosic fibres. The main varieties of synthetic fibres are polyester, acrylic, and polypropylene. Those of cellulosic fibre include viscose fibre and modal among others. Textiles made from these fibres are termed human-made textiles. They are used in various materials ranging from seat belts, ropes, bulletproof vests, to clothes (Preston 2016). MMF has seen a demand boom in the global market as well as the domestic market. The scheme was launched to capitalise on this growing market and place India at the forefront of textile manufacturing.

The Production Linked Incentive Scheme in Textiles

The Production Linked Scheme or PLI aims to increase India’s manufacturing capacity by giving incentives for incremental sales. The scheme has been approved for a total of 13 manufacturing sectors in India. These include the electronic, pharmaceutical, automobile, and textile sectors. The PLI scheme for textiles is set to be implemented for a period of five years from the FY 2025-26 to FY 2029-30 with a budget of 10,683 crores earmarked for the project. The main objective of the PLI scheme in textiles is to encourage the production of MMF in apparel, fabrics, and technical materials. These could be anything from clothes, winter wear, swimwear to items used in agriculture, defence, and the medical sector. The scheme participants would be investors willing to invest either INR 300 Crore or INR 100 Crore in capital building or civil works to produce a list of MMF products. The interested investor firm must be registered under the Companies Act, 2013. The scheme is incentive-linked, meaning it will give incentives over a level of turnover, 2 years into production. The PLI scheme is trying to boost manufacturing in India to create products that can compete on a global scale. This is being done by giving investors incentives on sales to invest in the capital building in India. While the scheme is meant to attract foreign investment capital, the manufacturing firms must be registered in India to avail of the scheme.

STRENGTHS

The Indian textile industry holds an important place in the domestic and global economy. It is a major player in the import-export sector, especially cotton. In terms of manufacturing, the sector contributed 7% to industrial production in 2018-19 (Indian Brand Equity Foundation [IBEF] 2021). It also employs the highest number of people after the agricultural sector, most of which are women. There are 4.5 crore people who are employed directly, and an additional 10 crore are involved in the allied sector (Invest India 2021). The Ministry of Textiles (2020) annual report records India being the second-largest producer of MMF after China and claims it to be the 6th largest exporter of textile and apparel with a share of 5% of the global trade. The industry predominantly produces cotton-based goods using cotton as raw material in 60% of the products. A closer look at the different components of cotton and MMF reveals the following chart.

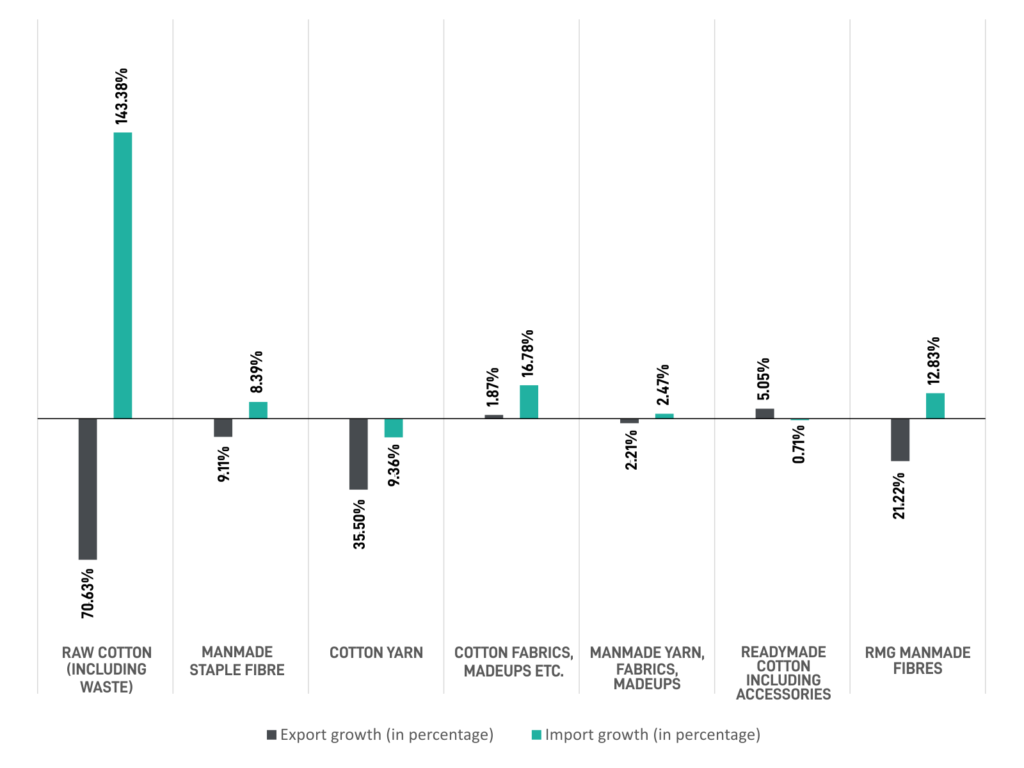

Figure 1: Import-export growth in cotton and MMF products from 2018-2019 (in Percentage terms)

Source Ministry of Textiles (2018a; 2018b).

The figure addresses the increase in import of raw cotton by an astounding figure of 143.38%, while the export decreased by 70.63%. The cotton yarn sector experienced a similar trend where exports shrunk. However, this is not all bad news. India has increased its exports in cotton fabrics and readymade garments [RMG], with their exports exceeding that of imports. This could signify India’s expanding production of finished products. Moreover, India’s own market for textiles has grown at a rate of 10% from 2005 to 2018, thus absorbing a lot of production (Wazir Advisors 2019).

WEAKNESSES

However, the import-export data over the years shows the dwindling picture of the Indian textile industry in the global market.

Figure 2. Import-Export growth in textiles over the years (in Percentage)

Source: Ministry of Textiles (2019a; 2019b)

According to the foreign trade statistics of India, the export of textiles has been declining gradually, except for the jump in the year 2019. Whereas the imports have been more or less increasing, except for the sharp dip in 2018. Even in 2019, the net exports were negative, with the value of imports being higher than the exports.

The Indian foreign trade outlook for MMF products also does not look good. Import of MMF ready-made products has increased by 12.38%, and exports have declined by 21.22%.

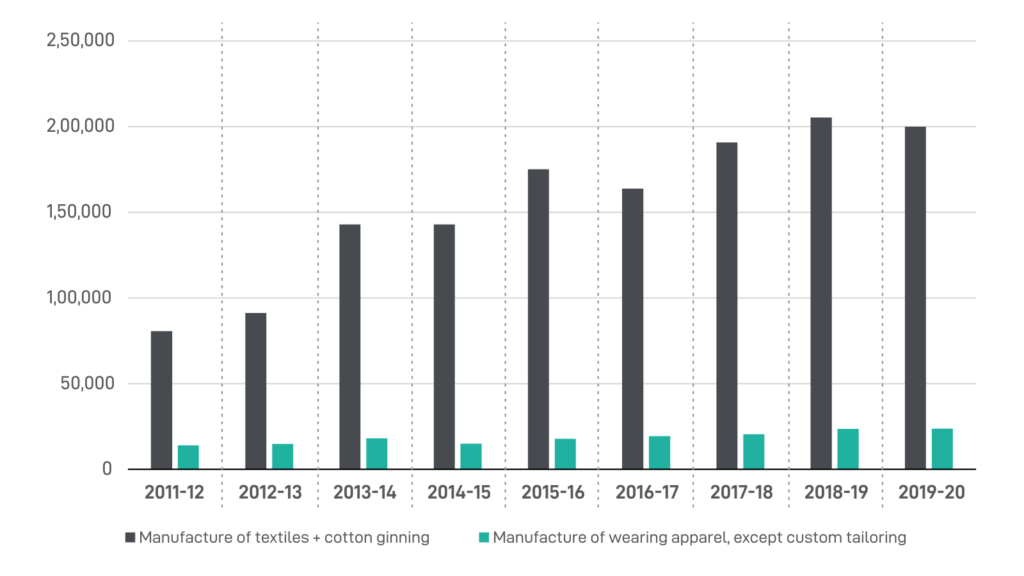

One of the significant components of the textile and apparel industry is cotton. The graph below (Figure 3) depicts the Indian manufacture of textiles, including wearable (ready-made) garments. The blue bars in the figure indicate that the manufacture of Indian textiles and the manufacture of ready-made garments has been increasing, signifying the higher need for cotton products.

Figure 3: Indian textile manufacturing from 2011-2019 measures at constant prices (2011-2012 prices)

Source: Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation (2019)

Current Challenges in Textile Production in India

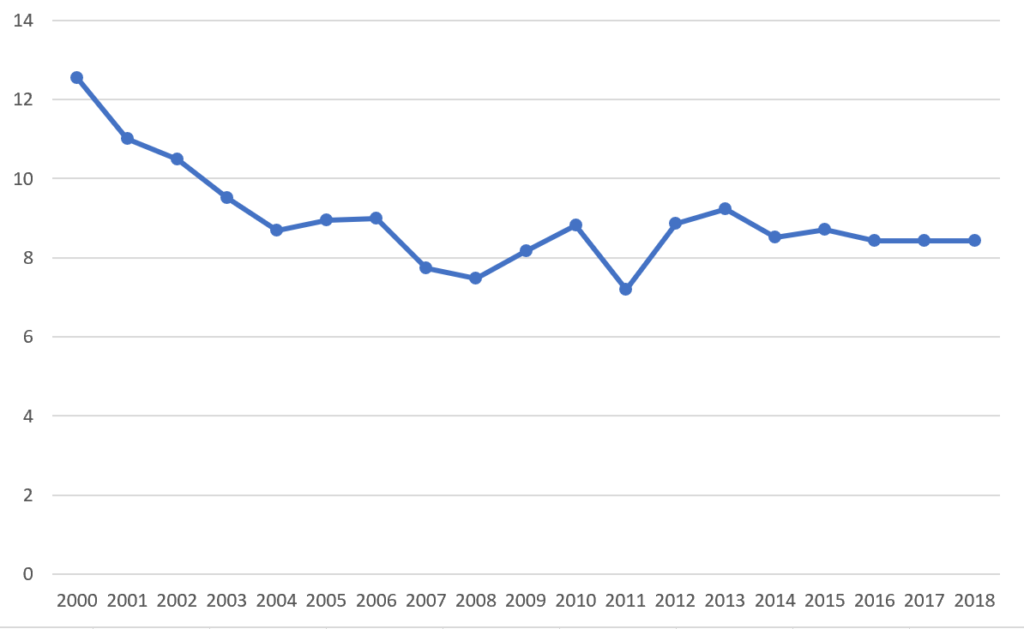

The World Bank (2018) data below shows the percentage value added by the textiles and apparel sector to the manufacturing sector in India (Figure 4). Value added is essentially the sum of gross output minus the value of intermediate inputs used in production.

Figure 4: Textiles and clothing (% of value-added in manufacturing) of India over the years

Source: World Bank (2018)

The figure shows the declining value added by textiles in the total manufacturing of India. This could signal the inefficiency in production (relative to total manufacturing), rising input costs, and the value of the final goods fetched in the market.

The textile sector is a significant sector after agriculture in the number of people it employs. In 2016-17, a significant portion of 18.1% of the total people employed in the manufacturing sector belonged to the textile industry (Ministry of Textiles 2016). However, according to the Office of The Development Commissioner for Handlooms (2019), 67.1% of the weavers earn less than INR 5000 per month, and 26.2% earn between INR 5001 to 10,000 a month. It is important to note that the low earnings of weavers factor-in labour cost while producing the textile, which, in turn, keeps the prices of final goods low and keeps the Indian textiles competitive in the global market. The handloom industry is also riddled with several other issues. It is highly unorganised with 77% independent weavers. It also has a low banking penetration at 23.3%, especially among women who form 71.6% of weavers, but has a shallow insurance penetration with an abysmal 3.3% in the rural areas (Office of the Development Commissioner for Handlooms 2019).

OPPORTUNITIES

The global trends reveal that the demand for cotton products is slowing down while non-cotton material is growing. The following table shows the average prices of various cotton and man-made products in the year 2018. It has been calculated using the average monthly prices in 2018 as provided by the Ministry of Textiles.

Table 1: Average of monthly prices of certain textile fibres in the year 2018

Source: Ministry of Textiles (2018c)

Viscose and polyester fibres fetch a higher price in the market (in average terms) compared to raw cotton. Similarly, man-made fibre yarn such as viscose filament yarn, nylon filament yarn, and poly-viscose blended yarn also get a higher price than cotton yarn. This suggests that MMF products are a lucrative market if compared to cotton. This could be a massive opportunity for the Indian textile market, which the PLI scheme seeks to capitalise.

THREATS

The scheme aims to improve Indian manufacturing in the global competitive environment. However, it will displace some of the key stakeholders in the textile industry. Therefore, it is essential to look at some of the issues that will emerge once this scheme is set into motion.

- Cotton farmers in India

This population segment will be severely affected by the scheme. Cotton productivity, as well as income, have stagnated in the past couple of years. Productivity in India was 9%, as compared to US’ 19.4% and China’s 22% (Food and Agriculture Organization 2009). The net income saw a decline of 26.33% in the period of 5 years from 2010-15 (Singh 2018). The scheme to boost manufacturing in MMF could further reduce the demand for cotton fibres, thus potentially worsening the farmers’ condition. Therefore, there is a need for additional policies to accompany the PLI scheme, which will improve productivity and income while keeping environmental sustainability in mind. For example, organic farming reduced production costs by 20% and increased the gross margins by 30-40% (Eyhorn, Ramakrishnan, and Mäder 2007). - Employment

The scheme is set to create additional 7.5 lakh job opportunities and lakhs of jobs for supporting activities. However, most handloom workers earn marginally low, even if employment in the textile sector is high (Office of the Development Commissioner of Handlooms 2019). Thus, it is vital to address the true impact of jobs created in terms of additional income for people. This is especially true for women employed in this sector who do not benefit from banking or social security measures. - The handloom sector and the skill and infrastructure development

The people involved in the handloom sector, such as weavers and spinners who were using natural fibres, will also feel the pinch in demand. Considering the unorganised nature of this sector, dispersing technical skills as well as infrastructural needs for the people in this industry would be a challenge. The Indian government must aim to develop the technical skills of small-scale textile and handloom manufacturers to produce quality products fit to survive the cut-throat competition of the global market. - Crude Oil

Production of synthetic fibres in the MMF textile sector uses crude oil as raw material. As a result, the prices and production of these fibres may be vulnerable to international and domestic oil prices. India has witnessed soaring prices of crude oil, (Radhakrishnan, Sen, and Jasmin 2021) recording an 80.6% WPI rate of inflation in 2021 in Crude Petroleum (as compared to 2020 according to DPIIT report 2021). While some of it is attributed to Covid-19 related disruptions in supply chains, India’s crude oil prices have grown at a CAGR of 16.6% (Gupta and Aggarwal n.d.). Therefore, these increasing prices can affect both manufacturers and consumers by making these fibres costly. It is important for India to focus on stabilising and lowering the prices of crude oil to attract investments in MMF textiles production.

REFERENCES

Food and Agriculture Organization [FAO]. (2009). FAO statistical database. Rome, Italy: FAO.

Office of The Development Commissioner for Handlooms. (2019). Fourth All India Handloom Census 2019-20. New Delhi, India: Ministry of Textiles. Accessed 10 November 2021, http://handlooms.nic.in/writereaddata/3736.pdf.

Singh, Amar. (2018). Cotton Statistics and News. No. 1. Mumbai, Maharashtra: Cotton Association of India. Accessed 11 November 2021, http://www.cicr.org.in/pdf/pop_art/double_cotton_reddy.pdf.

Thomas, Gilgesh and John De Tavernier. (2017). “Farmer-suicide in India: debating the role of biotechnology”. Life sciences, society and policy 13(1): 1-21.

Preston, J. (2016). “Man-made fibre”. Accessed 27 December 2021, https://www.britannica.com/technology/man-made-fiber.

Eyhorn, Frank, Mahesh Ramakrishnan, and Paul Mäder. (2007). “The viability of cotton-based organic farming systems in India”. International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability 5(1): 25-38.

Indian Brand Equity Foundation [IBEF]. (2021). Textiles and Apparel. New Delhi, India: IBEF. Accessed 15 November 2021, https://www.ibef.org/download/Textiles-and-Apparel-July-2021.pdf.

Invest India. (2021). “Textiles and Apparel”. Accessed 2 November 2021, https://www.investindia.gov.in/sector/textiles-apparel.

Ministry of Textiles. (2020). Ministry of Textiles Annual Report: 2020-2021. New Delhi, India: Accessed 4 December 2021, http://texmin.nic.in/sites/default/files/AR_Ministry_of_Textiles_%202020-21_Eng.pdf.

Ministry of Textiles. (2018a). “Export of India’s Textiles in T&A in US Million dollars”. Accessed 6 December 2021, http://texmin.nic.in/sites/default/files/7a.%20Export%20of%20Textiles.pdf.

Ministry of Textiles. (2018b). “Textile and Apparel imports from 2014-15 to March 2019”. Accessed 6 December 2021 http://texmin.nic.in/sites/default/files/7b.%20Import%20of%20Textiles.pdf.

Ministry of Textiles. (2019a). “Export of India’s Textiles in T&A in US Million dollars (2013-2020)”. Accessed 6 December 2021, http://texmin.nic.in/sites/default/files/7a.%20Export%20of%20Textiles.pdf.

Ministry of Textiles. (2019b). “Textile and Apparel imports (2013-2019)”. Accessed 6 December 2021 http://texmin.nic.in/sites/default/files/7b.%20Import%20of%20Textiles.pdf.

Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation. (2020). “Indian textile manufacturing from 2011-2019 measures at constant prices (2011-2012 prices)”. Accessed 6 December 2021 http://mospi.nic.in/publication/national-accounts-statistics-2021.

World Bank. (2018). “Textiles and clothing (% of value added in manufacturing) – India”. Accessed 6 December 2021, https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NV.MNF.TXTL.ZS.UN?end=2018&locations=IN&start=2000.

Ministry of Textiles (2016). “Number of persons employed/engaged in the organized Manufacturing Sector, Textiles and Wearing Apparel Sector as per Annual Survey of Industries”. Accessed 6 December 2021, http://texmin.nic.in/sites/default/files/2.%20Employmwent%20in%20organised%20Textiles%20and%20Wearing%20Apparel%20Sector.pdf.

Ministry of Textiles. (2018c). Indian Manmade Textiles Fibre Industry. New Delhi, India: Ministry of Textiles. Accessed 6 December 2021, http://texmin.nic.in/sites/default/files/Indian%20Manmade%20fibre%20textile%20industry_0.pdf.

Radhakrishnan, Vignesh, Sumant Sen, and Nihalan Jasmin. (2021). “Rising crude oil prices further burdens Indian consumers”. The Hindu, 1 October 2021. Accessed 6 December 2021, https://www.thehindu.com/data/data-rising-crude-oil-prices-further-burdens-indian-consumers/article36763438.ece.

Department of Promotion, Industry and Internal Trade. (2021). Index Numbers of Wholesale Price in India for the month of October, 2021(Base Year: 2011-12). New Delhi, India: DPIIT. Accessed 6 December 2021, https://eaindustry.nic.in/pdf_files/cmonthly.pdf.

Gupta, Richa and Umang Aggarwal. (n.d.). Will the build-up in crude oil prices put India’s growth under stress?. Haryana, India: Deloitte India.

Office of The Development Commissioner for Handlooms. (2019). Fourth All India Handloom Census 2019-20. New Delhi, India: Ministry of Textiles. Accessed 10 November 2021, http://handlooms.nic.in/writereaddata/3736.pdf.

Wazir Advisors. (2020). Annual Report of Indian Textile and Apparel Industry. Haryana, India: Wazir Advisors. Accessed 28 December 2021, https://wazir.in/pdf/Wazir%20Advisors_Inside%20View%20-%20Annual%20Report%20on%20Textile%20and%20Apparel%20Industry.pdf.