Context

According to the Sample Registration System [SRS], in India, between 2016-2018, the maternal mortality ratio [MMR] was 113 deaths per 10,000 live births – a decrease from 130 deaths per 10,000 live births between 2014-2016 (Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, 2021a). The government’s multi-pronged policy aims to curb home births and increase institutional deliveries through schemes such as Janani Suraksha Yojna [JSY] to improve maternal health and reduce MMR, particularly for rural women. The key focus of this scheme is States with low delivery rates or the ‘low performing states’ [LPH] such as Uttar Pradesh, Uttarakhand, Bihar, Jharkhand, Madhya Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, among others. Each beneficiary under this scheme is provided with a JSY card through which birthing mothers can avail cash assistance during delivery (Figure 2). Moreover, Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHA workers) are provided monetary incentives for bringing pregnant women to medical institutes for deliveries (Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, 2015).

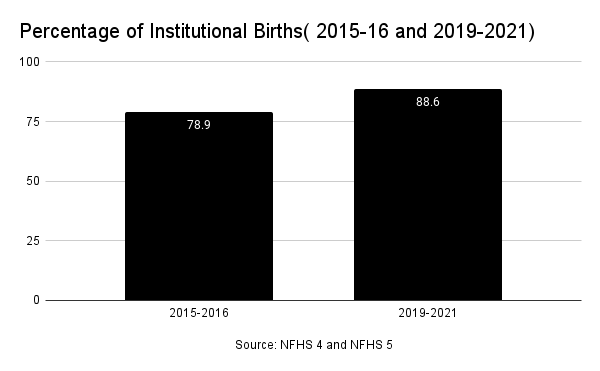

The government’s focus on institutionalising childbirth is evident from over a 10% increase in institutional births in 2019-2021 (88.6%) as opposed to 2015-16 (78.9%) (Figure 1) (Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, 2021b).

Figure 1: Percentage of Institutional Births (2015-16 and 2019-20)

Figure 2: Cash Incentives under Janani Suraksha Yojna [JSY]

| Category | Rural Area | Urban Area | ||

| Mother’s Package | ASHA’s Package | Mother’s Package | ASHA’s Package | |

| Low Performing States(LPS) | 1400 | 600 | 1000 | 400 |

| High Performing States(HPS) | 700 | 600 | 600 | 400 |

Source: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare (2015)

While this changing trend has been hailed as a positive step in improving the maternal health of birthing mothers, other accompanying trends that need attention are the increasing cases of caesareans, better known as C-section deliveries, and violence against birthing mothers in these medical institutions. This begs the need to explore the, often overlooked, impact of institutional deliveries. Herein the unwarranted use of drugs, surgical interventions, and biomedical procedures are employed by a section of medical institutions and health practitioners to transform natural stages of reproduction and birth into pathological states that require ‘treatment’ (Shrivastava & Sivakami, 2020). Such procedures thus become a critical part of obstetric violence.

What is Obstetric Violence?

The term obstetric violence, first recognised in March 2007 in Venezuela, refers to the mistreatment, dehumanisation, and abuse of birthing mothers by health practitioners and medical institutes. This includes breach of mothers’ informed consent or bodily autonomy and the controlling of their bodies and reproductive processes by health personnel (D’Gregorio, 2010). Obstetric violence is classified along with three broad but non-exhaustive categories. First is abuse, second is coercion, and lastly disrespect, which further includes forced surgery, unconsented medical procedures, sexual violation, and physical violation. The mistreatment by healthcare providers also includes sexual and verbal abuse, the poor rapport between women and healthcare providers, and inadequate healthcare facilities (Bohren et al., 2015; Kukura, 2017).

In her work among pregnant American women, legal practitioner Diaz-Tello (2016) discusses obstetric violence particularly in the case of forced caesarean surgeries. Through a series of case studies, she provides her perspective as a legal practitioner by positioning the forced caesarean surgeries and the disrespect towards pregnant and birthing women by medical practitioners and institutions as a violent act or what can also be classified as gender-based violence (Shabot, 2016). Considering the underlying power structures in a medical setting such as a clinic/hospital, Diaz-Tello (2016) argues that pregnant women are given less power than doctors. She provides instances of coercion and threat of legal intervention such as denying access to the newborn or deeming mothers unfit for childcare in cases where mothers did not consent to caesarean surgeries but were forced to adhere to doctors’ or medical institutions’ decisions.

It is critical to highlight that the use of obstetric violence entails not only the explicit use of physical force but also a wide range of strategies employed to secure women’s consent. This includes manipulating or withholding information such as presenting the possibility of brain damage or foetal death, exerting emotional pressure, the threat of abandonment by doctors. Economic threats in the form of refusing treatment and demanding advance bill payments for otherwise unwarranted expenses (Kukura, 2017) were also exercised. Studies within sociology and in biomedicine highlight that the employment of surgical intrusion to breach the personal and reproductive autonomy of birthing mothers leads to physical and mental distress. While childbirth in clinical settings is a terrifying experience for several women, the loss of dignity and autonomy during birth causes ‘birth trauma’ and postpartum post-traumatic stress disorder (Beck, 2004).

Understanding Obstetric Violence in the Indian Context

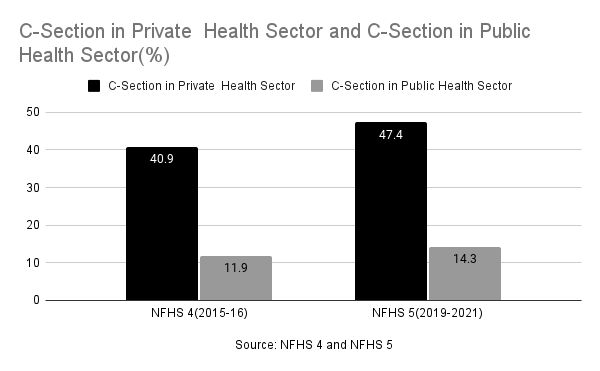

According to the World Health Organisation, the prevalence of C-sections should not exceed more than 10-15% (Department of Reproductive Health and Research, 2015). However, in India, the percentage of births through caesarean was 17.2% in 2015-16, while NFHS 5 recorded 21.5% caesareans in 2019-21 (Figure 3). During this period, the percentage of deliveries conducted through caesarean in private health facilities was three times higher as compared to public healthcare facilities (National Family Health Survey-5, 2021).

Figure 3: C-Section in Private Health Sector and C-Section in Public Health Sector (%)

In some cases, doctors in both private and public hospitals prescribe a caesarean since a surgical delivery takes less time and helps tackle the poor doctor-patient ratio. Studies on the patient’s perspective on accepting caesarean surgeries note that fear of vaginal delivery and social norms also play a critical role (Chattopadhyay, 2016). However, in the case of the private sector, studies have shown that corporate hospitals perform avoidable surgeries due to the pressure to meet the monthly quota for conducting medical procedures (John, 2015). Drawing from NFHS 4, studies note that on average, a standard delivery in a private health facility costs INR 10,814 while a caesarean costs INR 23,978, more than double (Press Trust of India, 2018). Thus, while on the one hand, avoidable caesareans lead to an increase in out-of-pocket expenditure and post-delivery care, they can also lead to complications such as delay in breastfeeding, lower birth weight of the newborn, among others.

In some cases, caesarean deliveries are indeed necessary. However, studies have shown that the rise in surgical deliveries is linked to a possible means for charging the patients higher than a normal delivery, either by misinforming the patients or coercing them to undergo the procedure during labour. The available public health literature in the Indian context traces linkages between socio-demographic factors and obstetric violence. Studies highlight the prevalence of physical abuse of women (slapping, punching, or beating) by healthcare providers, mistreatment during labour (tying of legs to iron rods), and verbal abuse in states of Uttar Pradesh and Gujarat (Goli et al., 2016; Chattopadhyay et al., 2018).

Among birthing women, while surgical incisions through caesarean and episiotomies ease birth, studies suggest the overuse of these procedures is prevalent, particularly in the absence of required medical facilities. The existence of malpractices and the performance of these procedures without the mother’s consent leads to severe risks for women and infants and emotional injury such as postpartum post-traumatic stress disorder. Unlike a caesarean where a woman is conscious about the procedure being performed, Kukura (2017) points out that in several cases, an episiotomy is performed on women without their informed consent or any prior medical indication. In many cases, while women are informed that labour will be induced artificially using drugs, they are not informed about the risks of such procedures, such as a heightened risk of infection.

Moreover, in India, inadequate access to proper medical care and healthcare facilities is impacted by the social position of women’s particular class, religion, caste groups, and larger power structures (Baru et al., 2018). For instance, findings of longitudinal studies in rural and urban areas of these two states delineate a higher proportion of discrimination and obstetric violence among Muslim women compared to Hindu women and poor women compared to their rich counterparts, respectively (Patel et al., 2015; Raj et al., 2017). However, despite the disproportionate dissemination of risk, self-reporting of abuse was minimal across women in all states, thus showing the normalisation of improper treatment during maternal care, often not perceived as abuse by healthcare providers or women.

Conclusion: Is Reproductive Health a Credence Good?

Social anthropologist Veena Das (2015) conceptualises health as a “good” or a commodity wherein an expert is expected to be more adequately aware of the benefits or the bane of the “good” than the consumer. Due to this “information asymmetry” between buyers (here, patients) and sellers (here, doctors), the latter take on the role of experts and see an incentive to be fraudulent, thus transforming a commodity into a “credence good” (Emons, 1997). The rising cases of unwarranted caesareans and obstetric violence thus prompt one to view reproductive health as a “credence good” – a good whose value and the extent of its requirement consumers are unsure about. With the commodification of reproductive health, one could argue that the bodies of women have transformed into sites on which institutional violence is exercised.

Moreover, as of 2018, The Clinical Establishments (Registration and Regulation) Act, 2010 and notified Clinical Establishments (Central Government) Rules, 2012, which prescribe conditions for registration and regulation of clinical establishments (both Government and Private) has been adopted by only eleven states and six union territories (Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, 2018). While a series of government schemes such as the Janani Suraksha Yojna, Janani Shishu Suraksha Karyakaram (JSSK), and Labour Room Quality Improvement Initiative (Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, 2019) has aimed to increase institutional delivery and quality care during childbirth, they have failed to take into account the asymmetrical dissemination of information between doctors and patients in India’s rapidly growing unregulated private sector.