Essay by – Neymat Chadha

Photos by – Pallavi Gaur

A child is not a tabula rasa who forms the understanding of the world as a passive observer. The contours of childhood and adulthood are often formed in relation to each other. Illness and diseases within the family, especially those of parents, transform children into bearers of immense knowledge of the world they inhabit. This shapes the course of the way disease and illness are experienced by the patient, who by virtue of being a parent is also expected to be a caregiver; the child thus takes on the role of learner, caregiver and active social actor. This is a story that seeks to show how children give expression and hope not only to their parents but also to themselves by creating stronger selves, spurred on by realisations and aspirations at the same time.

Shabana (20), mother of a one-month-old baby and Savita (19), training to become a lab technician, are neighbours in a colony in East Delhi. We met them through the Leprosy Mission Trust, India. Both of their parents were suffering from leprosy but now have been successfully cured. However, by the time the disease could have been diagnosed, they had already developed visible deformities.

When we first met Shabana in December, she was 8 months pregnant with her first child. During our conversation, we found out that her mother, who works in a factory, was abandoned by her first husband as she was diagnosed with leprosy after marriage. Following that, while undergoing her treatment in Dhanbad, she met Shabana’s father, Muneeb (name changed) who was diagnosed with leprosy as a child, affecting his feet, hearing ability and eyesight.

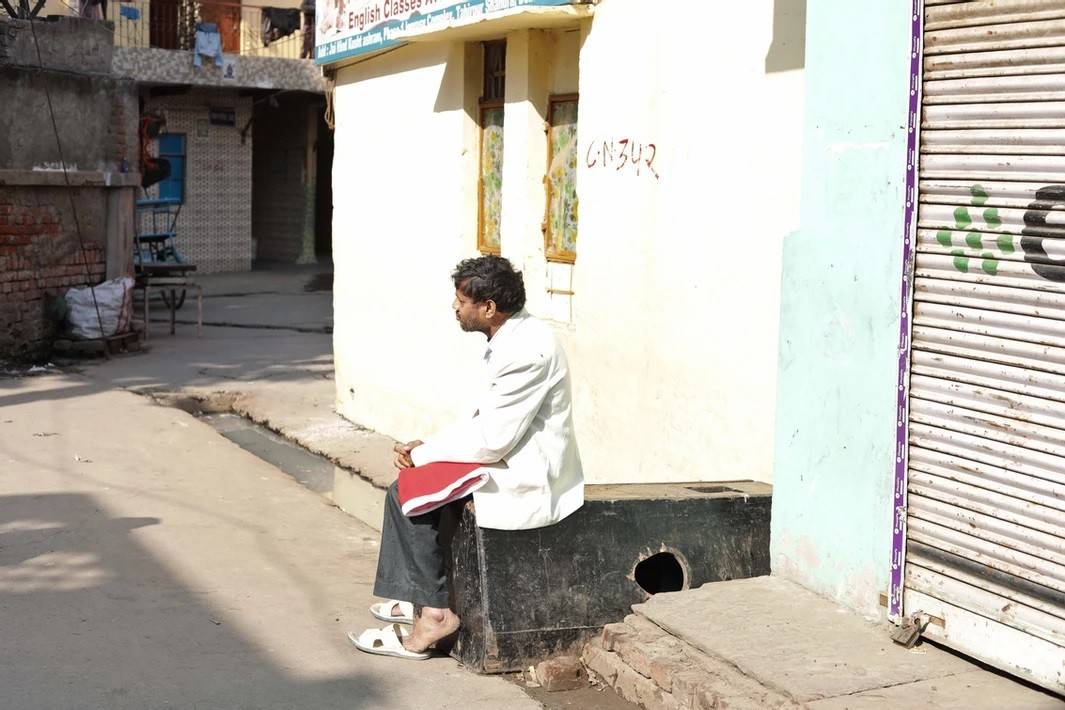

Having moved to Delhi in 1984, Muneeb worked as a tailor in Seemapuri. From our conversations with him, his love for tailoring and stitching was evident. His deteriorating eyesight, however, makes it difficult for him to continue. Sitting beside his tailoring machine, he recalls,

“Maine bahut jagah silai ka kaam kiya hai – Orissa, Patna aur Delhi. Main bachon ko bolta rehta hun silai seekh lo, koi dhyan nahi deta”.

(I have worked at a lot of places doing stitching work in Orissa, Patna and Delhi. I keep telling my children to learn stitching but no one pays attention.)

However, when asked about his aspirations for himself and his children, especially during times of being impacted by the “disease” of leprosy, he says,

“Sugar se bahut takleef rehta hai. Doctor sahab bole ki sugar ki dawai zindagi bhar lena padega.”

(I have high blood sugar. The doctor has told me that I will have to keep taking the medicine for my whole life.)

Unlike sugar ki beemari, Muneeb has lived with leprosy since he was a child. For him, leprosy has become a part of his everyday life, the new normal, which has made it almost impossible to recall what it is to lead a life without leprosy.

We visited Shabana again in early January. By then, she had given birth to a beautiful baby boy. Sitting on the bed with her baby in her lap, radiating an enormous amount of joy and warmth, the new mother beamed with a sense of gratitude and responsibility. Muneeb entered the room wearing a red and white Santa Claus cap, carrying another one in his hand. He sat down next to his sewing machine, smiled and handed over the cap to Shabana. He had stitched it for his newborn grandson.

Shabana’s neighbour Savita is undergoing training to become a lab technician in a hospital in Delhi. An ardent fan of ‘tik-toks’, Savita was our point of contact to help us navigate the streets of Shahdara. Having been brought up there since she was a child, she knows almost everyone in the neighbourhood. On our visit to her house, we met Savita’s mother Ishra. Ishra was born in Nepal. By the age of 15, before she even realised that she may have leprosy, she developed severe deformities in her hands and feet.

Basking in the sun while sitting next to her daughter, Ishra recalls,

“14-15 saal ki umar mein mujhe bimari ho gaya. Humari maa jadi booti ka dawai lagati thi. Jab bachpan mein bimari hua, yeh thodi socha ki bimari ho gaya. Khelti thi, ghoomti thi. Kal kya hoga, kabhi nahi socha.”

(I was diagnosed with leprosy when I was 14-15 years old. My mother used herbs to cure me. When I fell sick, I never thought that I had this disease. I used to play, roam around, without thinking about what will happen tomorrow.)

Soon after being diagnosed, one of her male cousins dropped her off to Delhi. That was the last time Ishra saw her family. The sisters at the Mother Teresa Home, Tahirpur (Missionaries of Charity) provided her with shelter, got her treated and subsequently got her married. Moreover, when Savita was born, the sisters organised a ‘lunch party’ for Ishra.

For Ishra, the meaning of family goes beyond blood ties. She considers the residents of the colony as well as the nuns at the missionary as her maika (maternal side of the family). However, she often wonders what she would say if she ever crossed paths with her biological family.

“Ab mere bachche hain, achchha pati hai. Agar zindagi mein aage badna hai toh jo hua usko bhool kar zindagi mein aage badna hai. Mujhe apne bachchon aur pati ke baare mein sochna hai. Agar maa baap se mili bhi toh kya bolungi? Kya hi bol sakti hun?”

(I have children, I have a husband. If I have to move on I have to forget about my parents and the family that abandoned me. I have to think about my children and my husband. Even if I ever speak to them, what will I say? What can I say?)

However, fearing alienation, Savita has not disclosed her parents’ struggle with leprosy at her workplace. She feels that people in the colony are more understanding as they can relate to each other, as in most of the families, at least one family member is suffering or had suffered from leprosy at some point in life. However, according to Savita, for ‘others’ to understand the challenges she faces outside, it is important for them to ‘have been there’. For Savita, even having her residential address on any valid identity proof poses a threat of alienation as even today, the colony in which she resides with her family is identified as a Kushtha Colony-

“School time tak toh theek rehta hai kyunki school bhi yahin hain aur sab ek doosre ko samjhte hain par service aur naukri mein dikkat ati hai. Jo bimari ke bare mein nahi jaante, vo aapas mein baat karte hain. Unko pata hi nahin hai leprosy ke baare mein aur vo samajh nahi sakte.”

(It is all fine till the time we are in school, as the school is within the colony. Everyone understands you because they have witnessed the disease and its impact just like anyone else in the colony. But the problem arises when we look for jobs, outside the colony).

Ishra adds,

Maine doodh pila kar bachchon ko bada kiya, chhoone se failta, toh inko na ho jata?

(I have fed my children. I have brought them up. If it were to spread through touch, wouldn’t they have leprosy as well?)

Given the myths around leprosy, one would expect stigma to play a significant role in alienating people suffering from leprosy and its subsequent impact, especially spatially in homogenising them in colonies. However, it is the colonies that take the form of a family, imbued in a profound sense of comfort, acceptance and hope within the colony, where a different normality is created. As Ishra says, “yahan main azaadi se ghoomti hun.” ( I roam around here with freedom).