By Kumam Davidson Singh

“The Pandemic has highlighted the fault lines that were already there; the biases against queer and trans communities and people living with HIV (PLHIV).” Pawan Dhall, Varta Trust

In two years of living with COVID-19, its profound impact on general structures, economies, and communities are well addressed. However, the phenomenon of reverse migration of queer persons, the economic recession in the transgender community, shrinking public spaces for transgender and queer persons, and the virus’ impact on people living with HIV (PLHIV) are less understood and documented. This photo story brings to the fore issues and impact of COVID-19 on LGBTQ communities and PLHIV in Manipur.

Transgender, gay/queer men, and gender non-binary persons in Manipur, especially in the valley, enjoy economic prospects and visibility in glamour, beauty, and entertainment. However, COVID-19’s long lockdowns crushed these industries. Findings from community-based research in Manipur shows a severe impact on their livelihood, mental health, community building processes and spaces.

At the same time, many transgender, gay/queer men and gender non-binary persons of Northeast India migrate to urban cities, drawn by the cosmopolitan lifestyle, economic prospects, and chance of escaping violent homes. Such individuals live outside Manipur and contribute significantly to the workforce, especially in the service sector. Unfortunately, COVID-19 forced many to return to their places of origin, often after losing their jobs. COVID-19 also indefinitely shut beauty parlours and saloons run by transwomen in small cities within the region. The ban on social gatherings such as marriages was a massive blow to them. In one instance, makeup artists and potloi designers resorted to working at paddy fields or any other odd jobs to sustain themselves. Livelihood opportunities vanished during COVID-19 lockdowns, laying bare the systematic and socioeconomic disparities.

The places transgender, gay/queer men and gender non-binary persons led economic activities shut. The spaces they used to occupy shrunk. Without economic activity that sustain workspaces, their subsequent social circles, intimacies, and identities that thrive in such places vanished too. COVID-19 entrenched already invisibilised lives into further isolation and often back into violent homes and colonies/leikas.

Transgender, gay/queer men, and gender non-binary persons found solace for their desires and intimacies in the streets at night since they avoided society’s scrutiny and ostracisation at that time. However, post-pandemic, they were pushed back within four walls of the house, where their intimacies and identities are ridiculed or silenced.

BT Park, where gay, bisexual, and other men who desire men hang out in late evenings, slowly coming back to life in winter in 2021 after lifting of the lockdowns.

Transgender and gay/queer men persons get together for a birthday party in her bedroom.

Another crucial issue that stems from the aforementioned community-based research is the impact of COVID-19 on PLHIV. Epidemics not only bring viruses and dead bodies, but they also bring virus-induced social stigma. There have been instances of COVID positive cases of transwomen being tagged as “COVID carrier”, echoing the traumatic “HIV carrier” term from the HIV epidemic that outcasted transgender, gay/queer men, and gender non-binary persons. Transpersons living with HIV [PLHIV] often bear the brunt of social discrimination and exclusion.

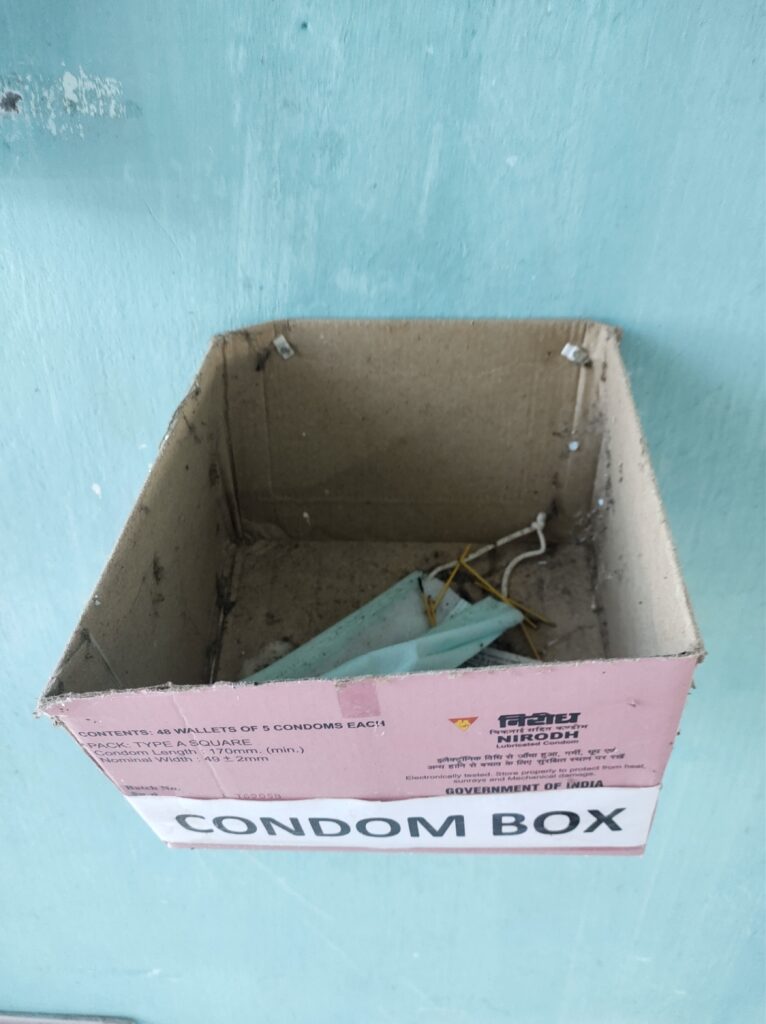

Viewed through a lens of stigma, their bodies are stigmatised as carriers of viruses. Unlike the response to COVID-19, which not only normalised virus infection and brought holistic health responses from every front, the stigma around HIV continues to haunt and kill people. Even after decades of HIV work across the world, the stigma remains intact and widespread. For PLHIV, the fight has not just been against COVID but also towards adherence to HIV medication and monitoring such as Anti-Retroviral Therapy [ART], viral load tests, regular blood work which the lockdowns, closing of hospitals, ICTC, and ART centres.

COVID-19 also impacted the community building processes as well as COVID crisis support. Though COVID relief did arrive in the form of ration and medical kits, it brought some scope of sustaining erstwhile community-building processes and spaces that nurture it. However, the question of economic sustenance and/or sustainable livelihood among transgender, gay/queer men, and gender non-binary persons have come to the fore all over again. We must ask if we have built a social system where transgender, gay/queer men, and gender non-binary persons can live economically sustainable, socially dignified, and empowered lives, especially in the face of global epidemics? And if the answer is no, we must strive to change that.

Kumam Davidson Singh is an ethnographer, writer, and educator based in Manipur. He is the founder of the Matai Society and co-founder of The Chinky Homo Project. His works have been published widely, including by Routledge and Zubaan.