According to the UNFPA (United Nations Population Fund), while the population of India is expected to see a rise of 56% between 2000-2050, the number of people aged above 60 and 80 will grow by 326% and 700%, respectively. The last 20 years have experienced a considerable fall in total fertility rate (TFR) and rise in life expectancy. We can, therefore, expect a significant rise in the percentage of elderly people in India in the next three decades. However, without corresponding psychological and social support, there is a persistent threat to the mental and physical wellbeing of this rapidly greying population. According to the 2011 census, there are more than 104 million Indians over the age of 60. Taking into account the change in the composition of the average Indian family in the last few decades, their futures are uncertain. Large, joint families have been increasingly giving way to smaller, nuclear ones; and a lot of Indians no longer live in the same cities or the same country as their parents. In such a situation, many elderly people in India are finding themselves helpless.

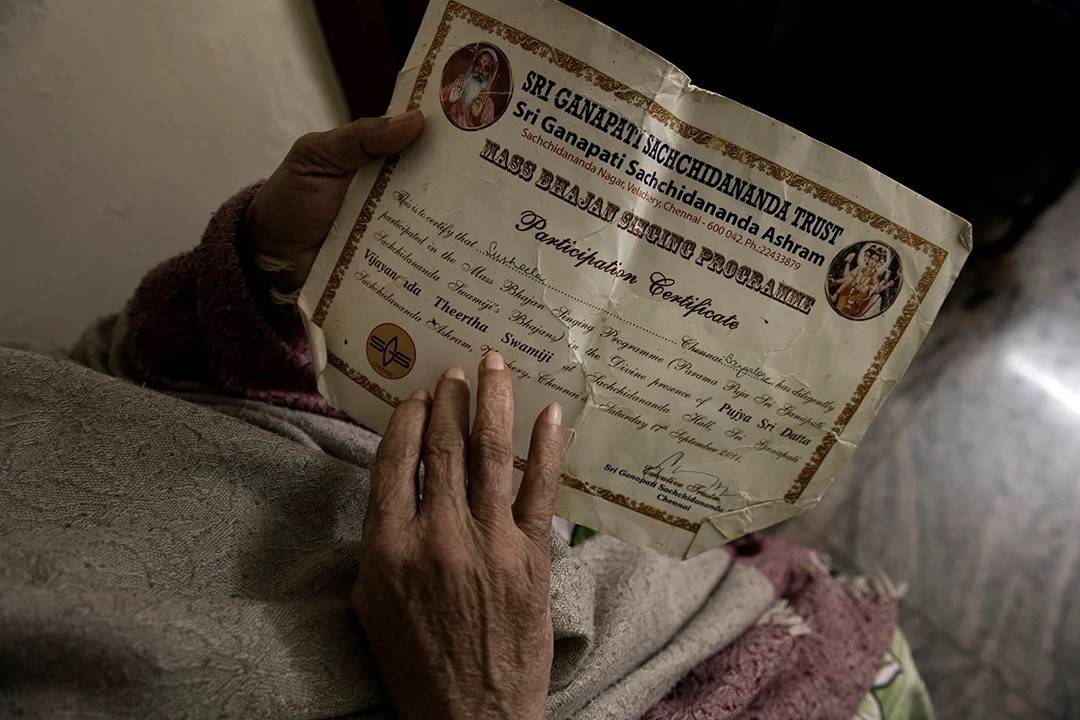

The AISCCON (All India Senior Citizens’ Confederation) 2015-16 survey shows that 60% of elderly people living with their families face abuse and emotional harassment, 66% are either ‘very poor’ or below the poverty line and 39% have been either abandoned or live alone. Insecurity, loneliness, and lack of companionship — some of life’s harder-to-swallow problems — become a daily reality for these people, whose children have either settled abroad or in some other city for better educational and career opportunities.

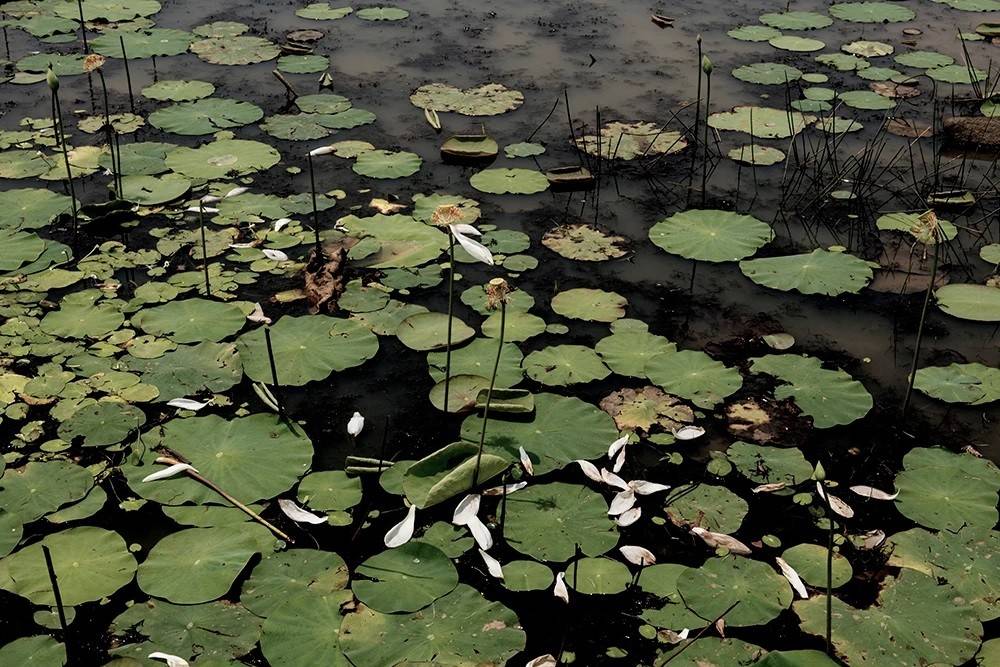

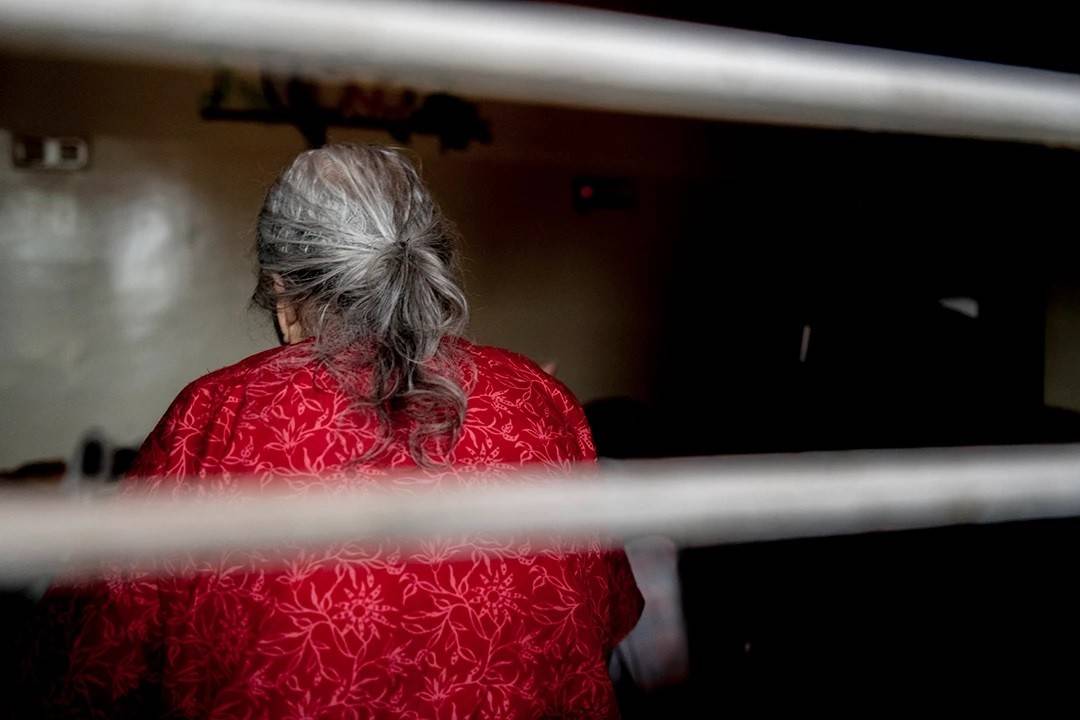

For the aged population living in care homes, life is both especially calm and chaotic. They suffer emotional distress because they never planned to breathe their last in care homes and traditionally, Indian culture endorses parents to plan their old age with their families. Many of the elderly people living in care homes do wait to return to their families before their deaths. But for the majority this is not an option, just like leaving their homes was not their choice in the first place. There is no reliable government data available on the exact number of elderly care homes in India.

Different kinds of disabilities become a reality for many aged people living in care homes. They are often unable to carry out simple, mundane tasks like bathing, dressing, eating, etc. without help. Many of them become immobile due to illnesses, falls, or joint problems. The highly institutionalized, depersonalized and bureaucratic atmosphere in elderly care homes leads to feelings of loneliness and dehumanisation. They find it difficult to adjust to new routines and new rules, and often fail to make new friends. Encountering frequent deaths of fellow inhabitants has a further negative impact, as many start counting the days of their own deaths. Often, they withdraw from life and embrace death by intentionally avoiding food and medicines.