As we sat down to discuss the finer points of this story, my co-author Aayush and I dwelled on the beginning of our shared love for football. The countless afternoons spent playing FIFA ‘98 as kids and watching players from our favourite video game in international football leagues on television catalysed our enthusiasm for the sport. However, for two fans of the game, growing up in the early 2000s in Delhi and Chhattisgarh, the football mania we observed in Europe and Latin America was absent in our neighbourhoods. Cricket, of course, was the favoured sport. While Delhi did have a sub-culture of football fans that I got access to only in college, even that was all but absent in Chhattisgarh for Aayush. Left out of India’s mainstream development story till it was carved out of Madhya Pradesh in 2000, Chhattisgarh lacked both facilities and exposure required for promoting sports at the grassroots. For kids with a passion for an already sidelined sport like football, avenues opened up only when one left the state.

Aayush himself first experienced Indian football culture after meeting players and fans from other states like Kerala, Goa, Bengal, and Manipur during his travels after graduating from school. Leaving his home state initially for work and travel, he gravitated towards the local football scene wherever he went, interacting extensively with those associated with the game, sometimes over a match or two. These interactions, he tells me, were revelations about Indian football and its history, which goes back two centuries. Pre-1960s, India was referred to as the ‘Brazil of Asia’. This much was evident in how India dominated Asian football, winning gold in the Asian Games during 1951 and 1962. As Aayush spent time with players on and off the field during his travels, he heard stories of youths playing football and cultures across the subcontinent that nurtured these childhoods. Alongside, he observed the general lack of documentation on the journey of Indian football in its historical, cultural, and political context. This inattention combined with poor media coverage has restricted appreciation for football to a few cultures and geographies within the country, unlike Cricket, which is a pan-India cultural phenomenon.

Aayush’s travels became a passion project during college to document Indian football through the lens of those who love it. Eventually, the journey brought him back to his home, Chhattisgarh, to capture the football scene in his state. One generally associates Chhattisgarh with the Maoist insurgency due to the years-long conflict and the media narrative around it. The Bijapur district in south Chhattisgarh underwent active violence as recently as April 2021 in a Maoist ambush that killed 22 security personnel (Sandhu 2021). Amidst the warfare, Aayush’s work documents the overlooked normalities in Bijapur by capturing young players practice shooting screamers at a government sports academy.

160 kms from Bijapur is the Mata Rukmini girls hostel in Jagdalpur, Bastar. The hostel not only provides accommodation and education facilities to 500 girls but houses its own girl’s football team. Most of the players are from nearby tribal villages. One would assume the insurgency to be the prime concern for these girls, but instead, they tackle patriarchal family and social structures during their pursuit of football. Resistance against women’s sports arrives in the form of discouraging players from wearing football shorts and concerns around playing while menstruating to questioning the scope of football as a sustainable profession and encouraging girls to take up gendered labour in their households. One of the coaches told Aayush that many skilful girls drop out of training because of such pressures. However, many also continue playing, keeping the spirit of the game alive. The coach also observed that the nature of the game trained the girls to replace anxiousness with fearlessness. This sportsperson discipline allowed them to become more independent and manage the pressures from their family through their love for the game. Though not all of them may professionally pursue football, they may learn to tackle problems from a position of power.

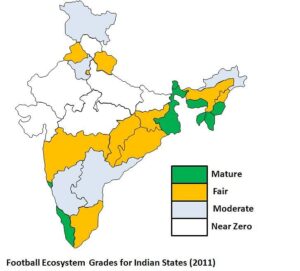

Aayush points out that, unlike south Chhattisgarh, there are more sports facilities in major cities like Bhilai and Raipur. Bhilai has a thriving sporting culture, owing to the facilities established in and around the city’s famous Bhilai steel plant. The plant’s football ground offers free coaching to children, many of whom come from the rural parts of the state. In Raipur, the state-of-the-art Kota stadium houses training facilities for both girls and boys. There is an observable difference in the availability, quality and access to training facilities and exposure in the two urban centres compared to the rest of Chhattisgarh. The concentration of resources within these urban centres makes it harder for players from the rural regions to gain access to better avenues to hone their skills, no matter their abilities. Here is where socio-economic marginalisation interacts with an individual’s passion for sports. A striking example of this is the slow evolution of sports facilities in Chhattisgarh, with resources and exposure reaching late to the region, compared to the rest of India.

Much of the state’s sports infrastructure is a recent phenomenon. Chief Minister Bhupesh Baghel’s ‘Khelbo Jeetbo Gadhbo Nava Chhattisgarh’ is a benchmark initiative in this context. The 2019 initiative established the state’s Sports Development Authority, which fast-tracked sports policy and promotion decisions. The state sports training centre in Bilaspur developed under the initiative was acknowledged as a centre of excellence by the central government’s Khelo India scheme for sports promotion (Kaiser 2021).

Despite all efforts, though, football still lacks the necessary infrastructural push within the new ‘Khelbo Jeetbo Gadhbo Nava Chhattisgarh’ initiative. Nevertheless, Aayush and the coaches he interacted with, note that more parents are increasingly open to sending their kids for football practice. Moreover, the eager to learn players Aayush met across the state expanded their exposure to international teams, tactics, formations, and skills through the internet and television. Seeing their national and international counterparts on-screen helps players navigate familial and societal barriers as they strive to represent their home state, which the rest of the country looks at only through the lens of the Maoist insurgency, in a positive light.

As I look through Aayush’s account of the football culture of his home state, a quote from one of the coaches stands out. Here is a rough translation: “A true player, even if she loses right now, plays to win in the evening. If she loses in the evening, she plays to win the next day. Ultimately, she learns to leave defeat behind.”