Growing up surrounded by seasonally-changing greenery and lawns within the household courtyard to play in is a privilege not many have experienced. However, Assam, with its signature style ‘Assam-type houses’, was a state that offered this privilege to most of its residents back in the day.

A contribution of the British in India, Assam-type houses flaunting a porch and space for plants and trees was a common feature around Assam’s capital Guwahati in the 19th century. Like with any metropolis, the city later had its own share of urban transformation.

The later part of the 19th century observed the city becoming a municipal region with municipal limits being drawn, spaces carved and formulated. Housing spaces began to be planned and defined by the city’s residents. Eventually, the wide and spacious housing spaces transformed into vertical, tall buildings to accommodate the rising population and lawns with colourful flowers started diminishing.

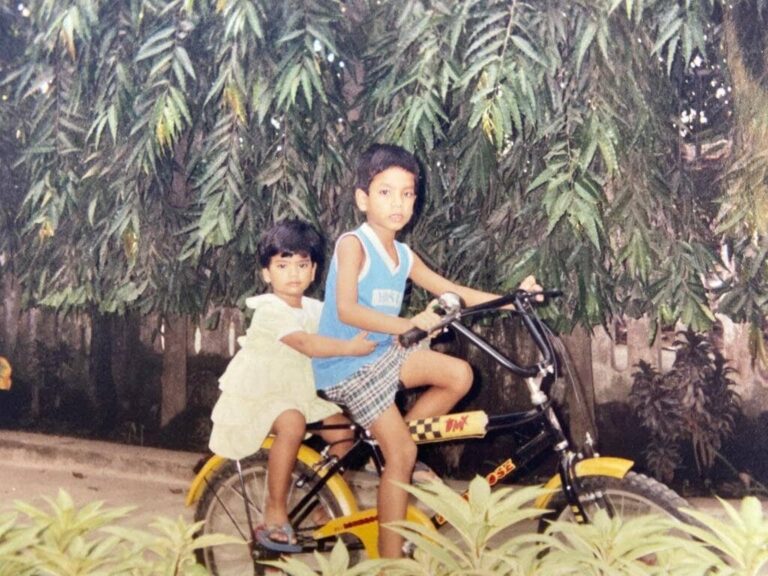

The photographs give us a glimpse of the ‘lawns’ from the early 2000s from an older part of the town called Bharalumukh. Bharalumukh, a locality in the southern bank of the river Brahmaputra, once upon a time had several residences with lawns and a variety of trees and plants on display. These gardens were integral to the spatial imagination of the dwellers who made Guwahati their living space.

Today, as the urban housing styles have transformed, one can only spot tall buildings with multiple floors, and only a few rare houses with lawns and greens remain. The changing seasonal flowers in those lawns, a topic of discussion for neighbours back in the day, have now been replaced with congested balconies in flats displaying a few hanging planters amidst drying clothes. While changing lifestyles and rising populations have compelled us to transform our residences, what remains alive is the yearning for a connection with nature.