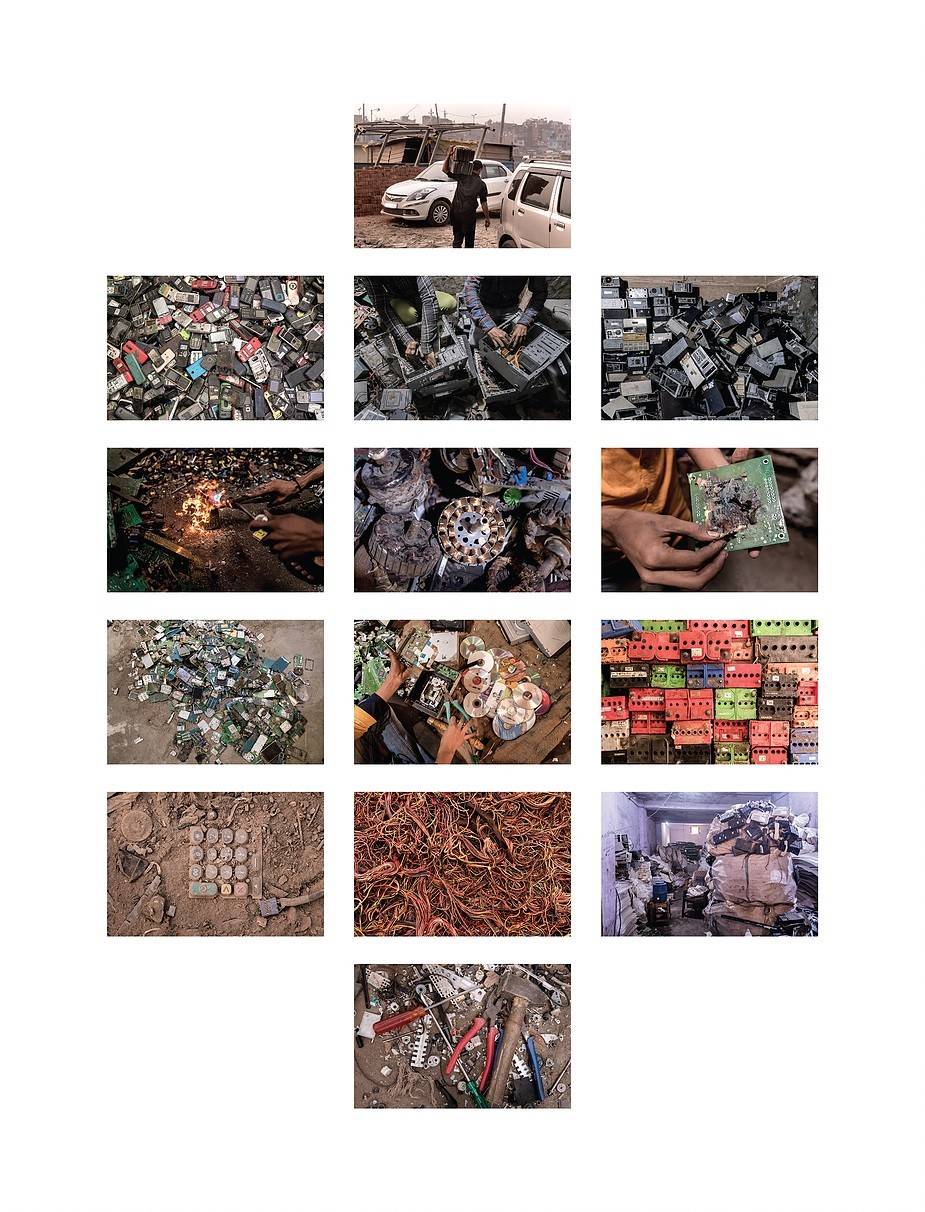

Photographs by: Sayan Hazra

Essay by: Jitendra Bisht

Over the past 4-5 years, national and international publications have documented the issue of e-waste significantly, if not frequently. The usual themes covered by such articles and reports are the recycling of e-waste, the largely informal nature of e-waste recycling, the health hazards and environmental concerns related to informal recycling, poor working conditions and the pre-existing socio-economic marginalisation of communities involved in the sector. However, with the frequent media spotlight on the sector, it seems documenting informal e-waste recycling, at least in certain parts of India, has become increasingly problematic.

E-waste refers to electrical and electronic equipment and/or their parts that have been discarded by their owners with no intent for further use. So everything from your laptop charger and its innards, to the LED bulb in your room, when disposed, becomes e-waste. As per an ASSOCHAM [1] study, Indians produce about 2 million tonnes of e-waste annually. Around 1/3rd of India’s e-waste comes from the states of Maharashtra (20%) and Tamil Nadu (13%). Also, 70% of e-waste in India is comprised of computer equipment, like the one I’m using right now to type out this essay. As per WHO, people involved in informal recycling of e-waste routinely come in contact with harmful chemicals like lead, chromium, cadmium, polychlorinated biphenyls and brominated flame retardants that can cause serious damage to the respiratory and nervous systems, in particular [2].

Based on our conversations with people in the sector, it seems e-waste is considered a lucrative business that brings in a substantial amount of income. This is because even the most basic circuit board contains precious elements like Copper and Gold that are “mined” through dismantling and burning, among other processes. Most people tend to overlook the health and environmental concerns that have been raised by successive reports over the years. In any case, it seems people have normalised the almost non-existent public health and sanitation infrastructure in such areas to the point that inhaling deadly fumes everyday is not perceived as deadly until the body shows overt signs of a medical condition.

Out of all the numbers associated with e-waste, the most striking is 95%, because that is the share of India’s total e-waste that ends up in the informal recycling sector. Informal recycling units are spread all over the country. They can be in the form of small one room units in low-income neighbourhoods and slums in cities, usually forming a larger kabaad market, or larger units in traditional family homes in rural areas. Over the last decade, and particularly since the introduction of E-waste (Management) Rules 2016, many informal recycling units have been sealed. Some of the recyclers we talked to tell us that, every time the sector is in the news or some new health or pollution report is launched, the local authorities raid such units. There is now a general reluctance and resentment among the people working in the sector towards journalists, photographers, NGO workers and basically any one who comes to document these areas. This is because of a fear of another article in the news or another report that could lead to police raids and sealing by municipal authorities. Members of some of the prominent civil society organisations working on e-waste attest to that fact, highlighting the need for a complete formalisation of informal recycling units and policies that can improve access to alternative livelihoods for people in the sector.

At the demand side, people like us, who are a part of India’s growing urban consumerist culture seem to be completely disconnected with where that new smartphone we bought only last year ends up. The cumulative impact of our choices and aspirations on the lives of many such hands that earn their living by dismantling our discarded electronics runs through multiple generations, in the form of physical ailments, as well as socio-economic outcomes.

Endnotes:

[1] https://www.assocham.org/newsdetail.php?id=6850

[2] https://www.who.int/ceh/risks/ewaste/en/