Introduction

The global landscape is witnessing a dual shift—population growth coupled with an increasingly ageing populace—a transformative trend unfolding across the globe, India included. As of 2022, India was home to 149 million individuals aged 60 and above, making up around 10.5 per cent of its population (International Institute for Population Sciences and United Nations Population Fund, 2023). Projections indicate a substantial rise, with the elderly demographic expected to reach 347 million by 2050, accounting for a significant 20.8 percent of the country’s populace (ibid.). This demographic shift poses multifaceted challenges, urging the formulation of proactive policies and comprehensive programs to cater to the evolving needs of India’s ageing population.

The ageing populace’s implications extend beyond societal dynamics, intertwining with economic dependency. As individuals retire, their income diminishes, while healthcare costs surge, intensifying financial strains. Amidst this landscape, social safety nets assume paramount importance. At the heart of this safety net rests the pension fund.

In the wake of the transition from the Old Pension Scheme (OPS) to the National Pension System (NPS) in 2004, debates comparing the two have persisted. However, in recent times, these discussions have gained considerable traction and prominence. As the population grapples with the implications of these systems, the discourse surrounding the merits and drawbacks of NPS versus OPS has amplified notably. Issues such as retirement income adequacy, investment flexibility, and the overall effectiveness of these pension schemes have been at the forefront of public and expert discussions. Moreover, as demographic shifts continue to emphasise the importance of sustainable retirement solutions, the discourse surrounding NPS and OPS has become even more pronounced and relevant.

Understanding Pension Systems in India: OPS vs. NPS

The retirement benefits for government employees in India have significantly changed over time. The erstwhile Old Pension Scheme (OPS), a fixed plan exclusive to government employees who have completed at least a decade of service, guaranteed a consistent monthly pension linked to their last salary. The government covered the entire pension, without deductions from the employee’s salary, throughout their tenure. Post-retirement, these individuals received their pension regularly along with a dearness allowance, adjusted twice a year in line with changes in the Dearness Allowance (DA), augmenting their pensions as the DA increased.

However, the landscape shifted in 2004 when the National Democratic Alliance (NDA) replaced the OPS with the market-linked National Pension Scheme (NPS). Initially exclusive to government employees, the Pension Fund Regulatory and Development Authority (PFRDA) made NPS available to both government and private sector employees, extending even to self-employed citizens from May 1st, 2009. Operated by the PFRDA, this optional program requires government employees to contribute 10% of their basic salary and DA, matched by a 14% contribution from the government. For other citizens, a minimum monthly contribution of ₹500 is accepted.

The NPS fundamentally differs from its predecessor, being a market-linked annuity scheme where contributions are diversified across government securities, corporate bonds, and shares, managed by registered fund managers under PFRDA’s purview. Upon retirement, individuals can withdraw approximately 60% of their total contribution, while the remaining 40% is utilised to procure annuities, facilitating a steady post-retirement pension setup. This shift represents a significant departure from the assured pension model of the Old Pension Scheme.

Table 1: Difference between the Old Pension Scheme and the National Pension Scheme

| Basis | OPS | NPS |

| Eligibility | Only government employees | Government employees, individual citizens between 18-60 years and NRIs |

| Basis of Pension | Provides pensions to government employees based on their last drawn salary plus DA | Provides pension based on the investments made in the NPS scheme during their employment |

| Pension Amount | 50% of the last drawn salary plus DA or the average earnings in the last 10 months of service, whichever is more, is given as a pension | 60% lump sum after retirement and 40% invested in annuities for getting a pension |

| Contribution | Employees do not contribute any amount | Government employees contribute 10% of their salary (basic + dearness allowance), and the government contributes 14% |

| Tax on Pension | The pension amount is tax-free | 60% of the NPS corpus is tax-free, while the remaining 40% is taxable |

Source: ClearTax (2023)

Why is OPS unsustainable?

In recent times, a significant uproar emerged within the governmental workforce, culminating in the “Pension Shankhanaad Rally” at New Delhi’s Ramlila Maidan on 1st October, 2023 (Mint, 2023). Central and state government employees, joined by public sector unit workers from over 20 states, united under a singular demand: the restoration of the OPS. The contention arises from the contrasting principles of OPS and the NPS. The OPS guaranteed retired personnel a stable pension directly from government revenue—equivalent to 50% of their last drawn pay—regardless of market fluctuations. On the contrary, NPS operates on market performance and employee contributions, absolving the government of direct pension liabilities. This contrast has sparked considerable dissent, particularly among government employees who view the NPS as a potential risk to their social security, favouring OPS’s stability without employee contributions.

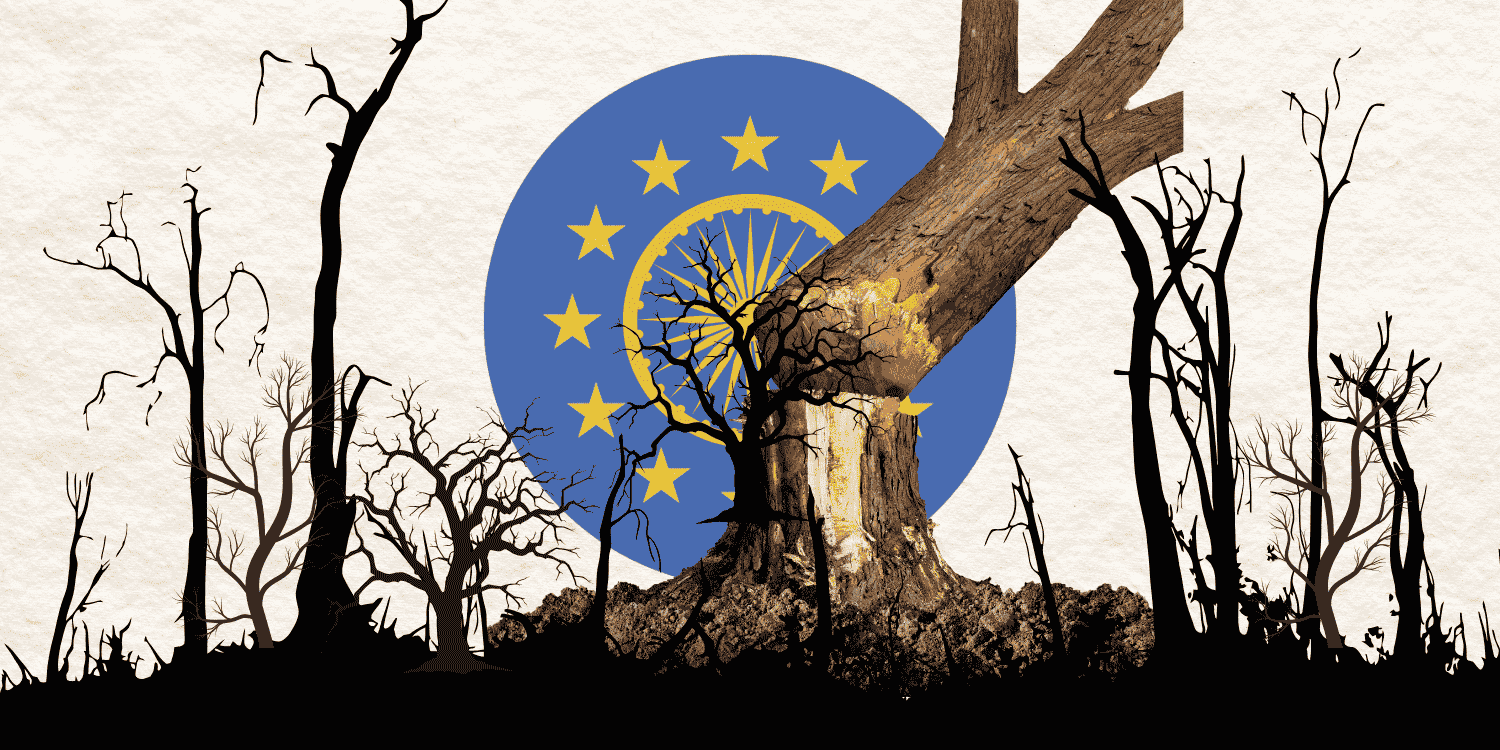

The reinstatement of OPS in certain states—Himachal Pradesh, Rajasthan, Chhattisgarh, and Punjab, governed either by the Congress or Aam Aadmi Party—reflects the growing resonance of employee demands for the return of the Old Pension Scheme (The Wire, 2023). However, these decisions have garnered cautious warnings from the Reserve Bank of India (RBI), citing substantial financial risks associated with reverting to OPS. An RBI study (Solanki et al., 2023) underscores the long-term financial burden, estimating a four-and-a-half-fold increase in government liabilities compared to the existing NPS. Despite short-term savings, the study warns of a looming surge in unfunded pension liabilities under OPS by the 2030s, potentially escalating to 0.9% of GDP annually by 2060 (ibid.).

Criticism of OPS extends to its perceived elitism, benefitting only a select few—government employees —while straining governmental finances. This intricate and contentious issue has emerged as a significant political focal point, with various political parties aligning their stance with employee demands, recognizing the potential electoral impact of addressing this highly charged matter.

Conclusion

The debate between OPS and NPS stands as a critical juncture, urging policymakers to navigate a path that harmonises fiscal responsibility, employee well-being, and wider societal consequences. As India confronts the challenges posed by an ageing demographic and the urgent need for viable retirement plans, the discourse around OPS versus NPS becomes central to the nation’s economic and social discussions. Deciding between OPS and NPS necessitates a nuanced strategy—one that guarantees financial steadiness while safeguarding the enduring welfare of retirees and the nation’s overall stability.