CATALYST

In September 2019, Tapir Gao, the Bharatiya Janata Party [BJP] MP of Arunachal Pradesh, cautioned the Lok Sabha that China had moved 60-70 kilometres beyond the McMahon Line, also called the Line of Actual Control [LAC], to construct a bridge within Indian territory. Gao warned that “if another Doklam were to happen anywhere, it would be here— in Arunachal” (Bharatiya Janata Party 2019).

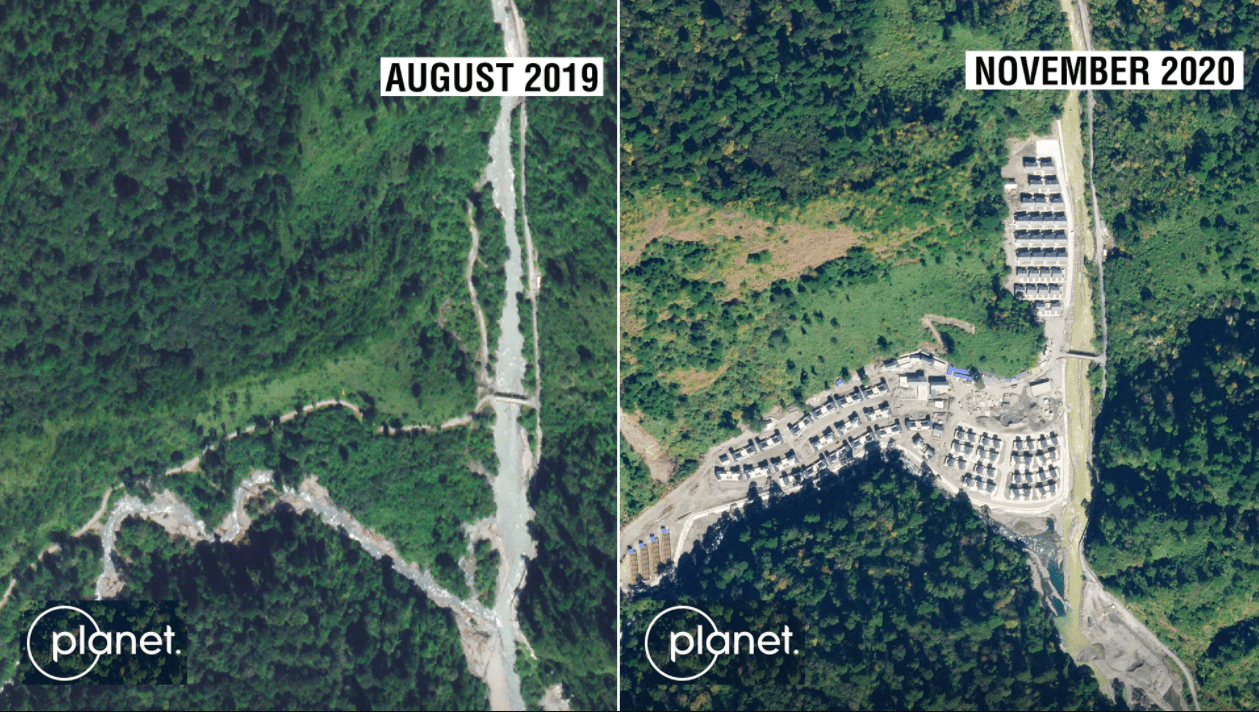

In following months, the suspicion that the Indo-China conflict would shift to Arunachal — proved true. In January 2021, news broke that Chinese troops had built an entire village in Arunachal Pradesh (Som 2021). Satellite images from November 2020 show 101 homes built 4.5 kilometres into Indian territory (Figure 1). Ministry of External Affairs confirmed they had received similar reports of China undertaking construction along the LAC.

Meanwhile, China contested the allegations by stating that it cannot be accused of trespassing since it never agreed to McMahon Line as the LAC. The Chinese foreign ministry continued this narrative, asserting that “all construction activity had been within China’s territory” (Lo and Zhang 2021), implying Arunachal Pradesh is Chinese property. They justified building the village as a part of their poverty alleviation scheme for the Tibetan region, expressing their intent to construct a total of 624 more villages on the disputed border (ibid). The Global Times, the Chinese Communist Party’s mouthpiece, published that the area India claims as Arunachal Pradesh is actually South Tibet, which the Chinese Government never recognised as Indian (Sikun, Yusha, and Siqi 2021) and can, therefore, build in.

This diplomatic friction outlines why many experts caution that the Indo-China dispute may be shifting east, especially to Arunachal Pradesh. The natural question that comes out of this is if most nations today respect their international borders to maintain peace and sovereignty, why can India and China not do the same in Arunachal?

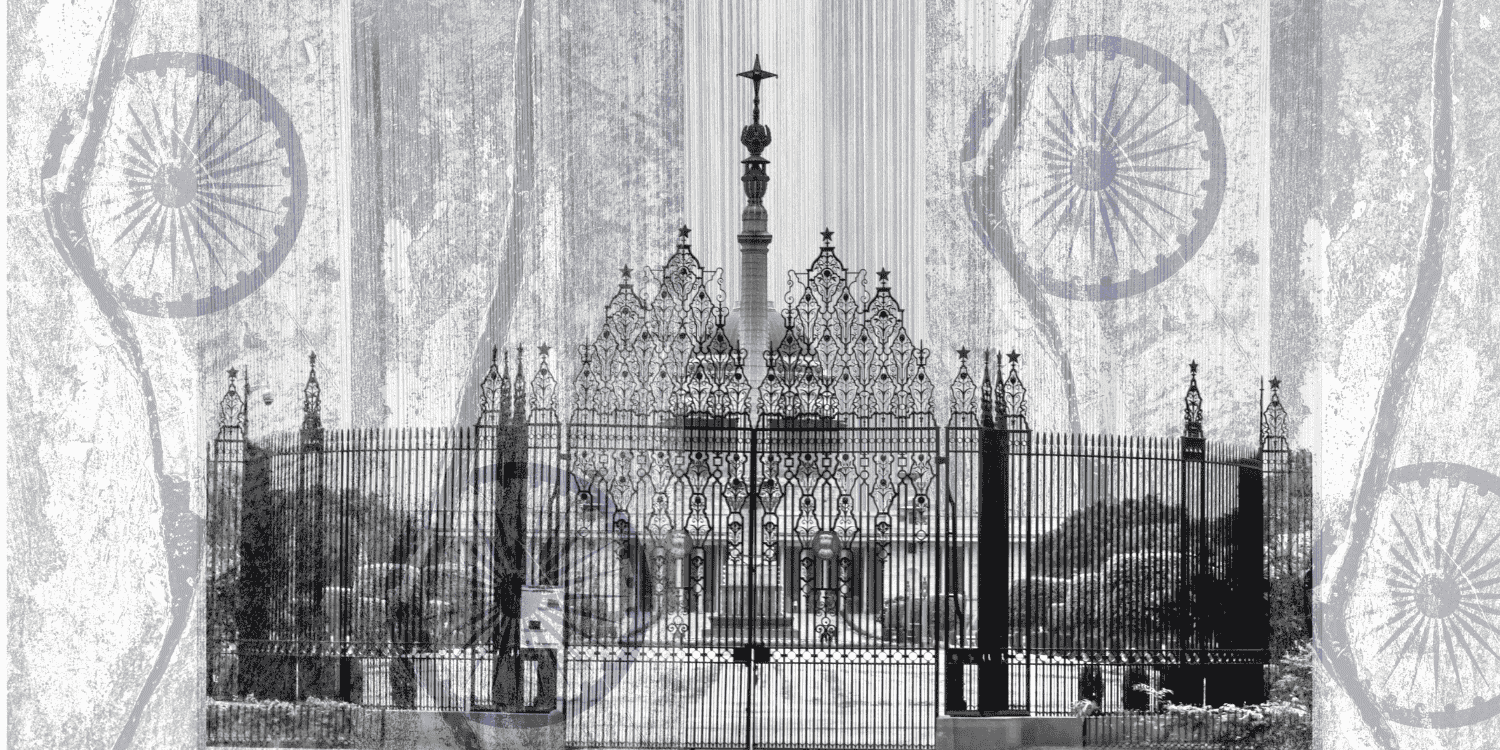

The simple answer is because the two neighbours do not have a mutually accepted and demarcated border. As of now, both nations tip-toe around the LAC status quo (Figure 2), which is disputed too.

HISTORY OF THE McMAHON LINE

The longer, more nuanced answer lies in the history behind the creation of the McMahon Line.

Colonial powers were in the habit of using ‘water parting’ to determine international borders. Water parting was the colonial practice of dividing land based on its natural topography that separated waters flowing to different water bodies (Gardner 2019), regardless of the inhabiting communities and the socio-political situation on the ground.

Currently, three colonial-era boundaries constitute the disputed Indian border with China. These are the 1865 Ardagh-Johnson line encompassing Aksai Chin into Ladakh, the 1893 Macartney-Macdonald line running along the Karakoram range following the Indus River watershed, and the 1913 McMahon line forming the current-day Arunachal Pradesh border with the eastern Himalaya’s watershed.