Introduction

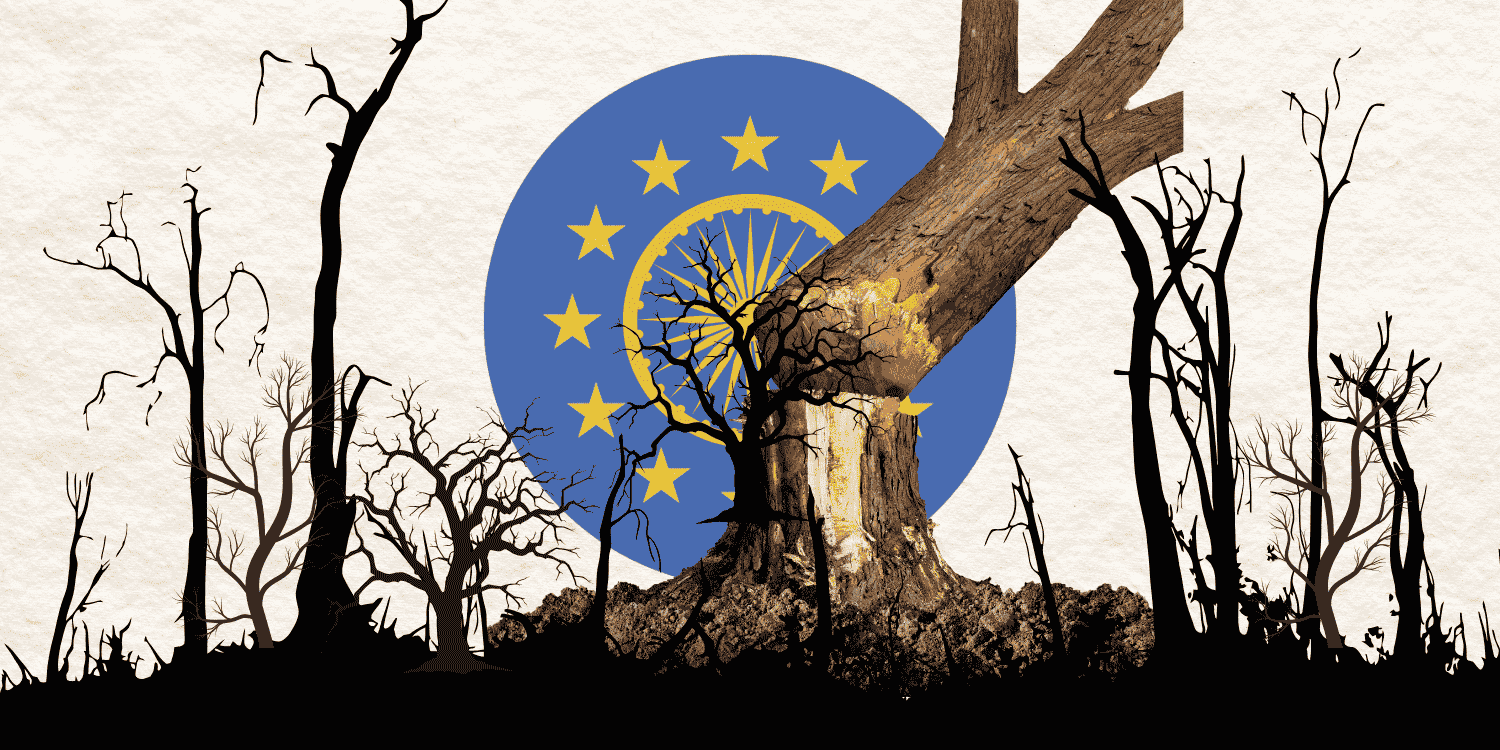

The European Union has been at the forefront of global climate policy, aiming to achieve carbon neutrality by 2050 under its European Green Deal. To support this goal, the EU has introduced several measures, including the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM). The CBAM has been viewed as a key intervention to reduce carbon leakage. The term carbon leakage is the phenomenon where a country’s efforts to reduce carbon emissions through domestic policies are undermined by companies relocating production to countries with less stringent environmental regulations, thus allowing for ‘leakage’ by exporting their emissions.

For over a decade, the EU has focused on reducing sectoral and subsectoral risks of carbon leakage.

The first list of sectoral and subsector risks became applicable in the 2013-2014 period. In the latest list released in February 2019, from 2021 to 2030, the sectors include mining of hard coal, extraction of crude petroleum, mining of iron ore, manufacturing of oils, fats, sugar, malt, leather clothes, cement, lime, basic iron, steel and copper to name a few (Official Journal, 2019). The list also includes aluminium production and other non-ferrous metal productions.

The CBAM is a policy tool designed to put a carbon price on imports of high-emission goods to the EU, ensuring that the European market is not disadvantaged by stricter domestic climate policies. It is an extension of the EU Emissions Trading System which is a cornerstone of their climate policy, designed to reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions by putting a price on carbon (EU ETS, n.d.). Under this system, the domestic manufacturers of any carbon-intensive goods must purchase allowances for each metric ton of carbon dioxide they emit. The CBAM matches these provisions with those from manufacturers and producers outside the EU, intending to protect domestic manufacturers from unfair competition from countries with weaker climate regulations.

Since the CBAM ensures that foreign manufacturers are subject to the same carbon pricing provisions as those within the EU, these policies are likely to impact major exporting countries like India, Russia and Turkey significantly. The waves from this policy have exposed Indian exports, trade, and employment to unstable ground despite reassurances from the EU that India could evade these challenges by putting a domestic carbon tax in place (Tiwari & Anand, 2024). For example, India has taken over Japan to become the second-largest producer of crude steel in the world, which contributes about 2% to India’s GDP and employs some 6 lakh people directly and a further 20 lakh people indirectly. The industry holds great potential to boost India’s economy however, trade fluctuations are likely to have a long-lasting impact on the sector (JSW, n.d).

Understanding the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism

The European Union has long sought to establish itself as a global leader in climate action. As part of its ambitious climate change strategy, the European Commission unveiled the “European Green Deal”, a flagship initiative to achieve climate neutrality by 2050 to make Europe the first net-zero continent.

The pioneering policies launched in 2019, mark a key milestone in the EU’s long-term commitment to reduce GHG emissions, boost clean energy, and promote sustainable economic growth; necessary steps that all countries in the world are committed to. During an initial transition period of three years, which began in 2023, the CBAM allowed companies and trading partners time to adjust applying only to selected products from heavy industries deemed as high risk of carbon leakage and highly GHG emission-intensive such as iron, steel, aluminium, cement and fertilizers (Berahab, 2022). By the end of the transition period, importers to the EU will pay a financial adjustment and the scope of the mechanism will expand to other products as well (Berahab, 2022).

Key policies and interventions include the EU Emissions Trading System, designed to price carbon emissions more effectively, investments in renewable energy, protecting biodiversity and ecosystems and most importantly, the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (EU Commission, 2023). The CBAM is a double-edged sword as it is both a climate policy tool but also, a “protectionist” measure taken to not only safeguard the environment against unsustainable manufacturing but also for European manufacturers from global competition. On one hand, it is designed to prevent “carbon leakage —the practice where companies relocate production to countries with weaker emissions regulations to avoid climate costs. By imposing a carbon price on imported goods from high-emission industries (such as steel, cement and aluminium), the EU argues that CBAM levels the playing field.

However, many countries (including India) see CBAM as a protectionist move that disproportionally impacts emerging economies and developing nations, particularly those that have large exports to the EU.

While this move is presented as an incentive by the EU for global decarbonization, it fails to recognize that many developing countries lack the resources and infrastructure to transition to low-carbon production- not simply that they are unwilling to do so.

The Politics of Carbon Leakage

Although carbon leakage has been promoted as an effective environmental safeguard, it is deeply rooted in historical emissions patterns, global trade dynamics, and power imbalances between developed and developing nations. Although global outsourcing has been a key part of global labour market since 1960s and 1970s when the first wave of global outsourcing began for production jobs in shoes, clothing, cheap electronics, and toys (Gereffi, 2005), in the year leading up to the 2008 Great Recession, offshoring became an important strategy for many companies in developed countries to maximise profits. The companies realised they could benefit from low-skilled production and labour, less stringent environmental laws and enhanced productivity (Acevedo & Abreha, 2024).

During this period of the early 2000s, these production changes led to “emission transfers” which were growing at stunning rates with more and more Western countries shifting their manufacturing to Asian countries (Plumber, 2017). These trends show that developed countries in Europe and the United States played a significant role in creating the conditions for carbon leakage by outsourcing carbon-intensive production through trade policies. The EU’s approach with their new CBAM reflects a broader pattern where developed economies, having long benefited from outsourcing emissions-intensive industries to developing countries, introduce regulatory mechanisms to address the very trade imbalances they contributed to.

Glen Peters, a scientist at the Center for International Climate Research and a key figure at the Global Carbon Project pointed out this ‘sanctimonious’ practice by the developed countries and highlighted the absence of any policy implications of this outsourcing under international mechanisms, such as the Paris Agreement less than a decade ago (Plumer, 2017). Peters also suggested that there is little direct evidence to show that the climate policies of these developed nations have driven large-scale carbon leakage. Rather than companies physically moving production facilities, carbon leakage primarily occurs through international trade shifts which would mean that the CBAM would not address the actual problem but only impose trade restrictions on imports from developing countries.

Moreover, instead of providing developing countries with much-needed support to transition, CBAM penalizes them for emissions linked to industries that were originally moved there and added to emissions by Western countries and companies.

India’s Carbon-Intensive Export and Impacts

The European Union is a significant marker for India’s heavy industry exports, the country has thus been placed in a challenging spot with the implementation of the CBAM. India’s steel industry is confronting significant challenges due to the EU CBAM. Data sources reflect that India’s exported finished steel to the EU is worth approximately INR 29,534 crores (PIB, 2024). Italy and Belgium are the biggest importers of Indian steel approximating nearly 22.3% and 11.2% of the exports of finished steel from India (Kumar, 2024).

The mechanism would involve import quotas, allowing steel imports within a specified limit to enter with zero or reduced tariffs. Exceeding these quotas results in a 25% tariff. Given that the EU accounts for a substantial portion of India’s steel exports- this range is very close for India and any reduction would adversely affect Indian exports (Kumar, 2024). Furthermore, the CBAM is set to be fully operational by 2026 and aims to impose tax on imports based on their carbon emissions. This additional duty could value up to €173.8 per tonne, equating to 16.06% of the unit value of steel exports as of 2022 (Pandey, 2025).

Similarly, India’s iron exports to the EU are poised to face significant challenges. In 2022, nearly 27% of India’s iron, steel, and aluminium exports were destined for the EU market (Arp, 2025). Due to India’s continued reliance on coal, India’s carbon emission intensity of its iron and steel is significantly higher than the EU average, making the imports from India much more costly under the CBAM (Arp, 2025).

The Centre for Social and Economic Progress (CSEP) conducted a study titled “Assessing the Impact of CBAM on Energy-intensive and trade-exposed (EITE) Industries in India,” focusing on the potential effects of the European Union’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM) on India’s EITE sectors. The research indicates that a 10% increase in fuel costs correlates with a 2.41% decrease in export earnings and a 0.23% reduction in employment within these industries (Grover, Ranjan & Kathuria, 2023).

The global community including India have criticised the EU’s move and proposed putting customs duties in place in retaliation (Reuters, 2024). Amid these geopolitical tensions, big private players such as ArcelorMittal are considering a potential shift of their European support activities (Peverieri, 2025) to India but not steel manufacturing—this continued trend of offshoring industries to developing countries continues to put pressure on India in terms of their climate policies and meeting the standards of support.

The EU has proposed that India impose a carbon tax, highlighting the need for a domestic carbon pricing mechanism however, despite setting up this mechanism India would not be able to match the EU’s carbon price levels. Since carbon prices are based on a country’s economic situation, a developing country like India cannot match EU or international carbon prices and thus a local tax cannot solve the issues that come up due to the CBAM (PTI, 2024). While India does not have a direct, explicit carbon pricing mechanism at current, it has remained wary of setting energy reduction targets. It utilizes schemes like the Perform, Achieve, and Trade (PAT) program to indirectly put a price on carbon by setting energy reduction targets for industries and allowing them to trade Energy Saving Certificates (ESCerts) if they exceed their targets (BEE, n.d.). This essentially creates a market-based approach to emission reductions. The PAT scheme in its first cycle was designed to reduce specific energy consumption (SEC) of production of 478 industrial units in 8 sectors which included Aluminium, Cement, Iron & Steel among others (BEE, n.d.).

Additionally India has also placed a tax on both imported and domestically produced coal since 2010 (Ellerbeck, 2022). Steel production is a coal intensive industry and India remains among the less efficient countries in terms of coal dependence for major steel production (Sengupta, 2024). Although India has defined the terms for green steel, these address domestic concerns and remain low as compared to international standards (Sengupta, 2024). The Indian steel ministry has also requested the government for support seeking around INR 15,000 crore from the Budget to offer incentives to steel mills to produce low-carbon steel (Sengupta, 2024 however no specific provisions have been made in the recently announced Union Budget.

Conclusion and Way Forward

As the EU has implemented the Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), India must also adopt a proactive approach to mitigate the risks and recognise emerging opportunities. At the same time, the Trump administration has also increased tariffs on steel increasing pressure on the exporters like India and China (Mishra, 2025).

As a major steel producer, India is directly impacted by geopolitical trade shifts, which influence its market competitiveness, export dynamics and compliance with evolving global sustainability standards. In light of significant trade challenges and surmounting global pressure; Indian industries must accelerate decarbonization efforts by investing in clean energy, energy efficiency and low-carbon manufacturing technologies. A crucial step in this transition within the steel manufacturing heavy industry is ResponsibleSteel, a global standardization and certification initiative aimed at promoting low-carbon, ethical and sustainable steel production. Notably, JSW Steel, one of India’s largest steel manufacturers, has joined the initiative, signalling its commitment to international sustainability standards (RS, 2023) and paving the way for other steel manufacturers in the country.

Consequently, India appears to have limited options: it must either reassess its trade strategies by exploring alternative markets with more favourable tariff regimes or accelerate domestic decarbonization efforts to align with global standards. Diversifying export destinations to other regions within the South Asia region would also allow for greater regional cooperation but the practical implications from other Asian countries like China can potentially challenge this effort. Simultaneously, investing in clean energy and sustainable manufacturing technologies would enhance India’s competitiveness in key markets.

By embracing these global standards, India can future-proof its heavy industry however these changes will take time, requiring significant investment and structural adjustment. In the meantime, India must build momentum by amplifying the voices of the developing countries’ voices challenging the protectionist policies of developed nations and advocating for a fairer global trade framework.