INTRODUCTION

In June 2021, Bharatiya Janata Party [BJP] MP John Barla raised a controversial demand for the separation of select North Bengal districts into a Union Territory. He argued that North Bengal has remained significantly underdeveloped in comparison to the rest of the state (Express News Service 2021). Following Barla’s rationale, BJP MP Saumitra Khan raised a similar demand to carve the Jangalmahal region into a separate state. Both the union and state governments have stated that they do not support the division of Bengal presently. However, the appeals for separation surfaced at a time when the National Gorkhaland Committee, All India Gorkha League, and Communist Party of Revolutionary Marxists submitted memorandums demanding the creation of Gorkhaland (Chettri 2021).

Politics in North Bengal has remained especially contentious since colonial times. The socio-political tensions in the region have assumed a new dimension in recent times wherein demands for statehood and sub-national autonomy are gaining momentum. These tensions underpin broadly two separatist movements: Kamtapuri and Gorkhaland.

Therefore, it is critical to position separatist demands and movements in the broader historical narrative to better understand their genesis, development, and viability. Especially as they surround ethnic unrest and self-determination in post-colonial North Bengal.

Keywords: Autonomy, Gorkhaland, North Bengal, Historical Demography, Partition, Rajbanshi, Self-determination.

PARTITIONS AND THE TRANSIENT DEMOGRAPHIC PROFILE OF NORTH BENGAL

Bengal has seen multiple partitions over the past century. Along with regional reorganisation, partitions give way to demographic, socio-political, and economic changes. Therefore, the question of separatism and ethnic unrest in North Bengal is rooted in the region’s changing demographic profile.

Post-colonial India (1947)

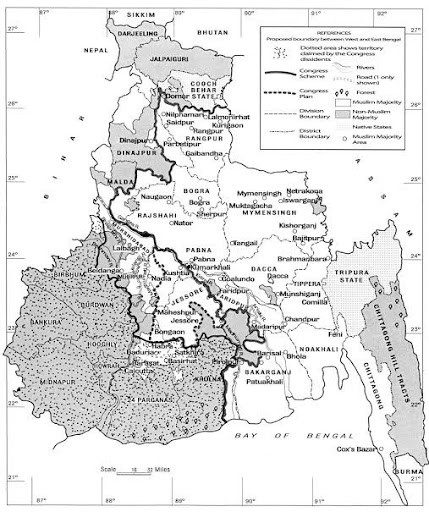

India’s partition or Great Divide of 1947 is widely remembered as the dismemberment of Bengal across generations. It is an event that redefined South Asia as a socio-political unit. While in Punjab, the bulk of partition-related migration was over by the end of 1947, migration of Bengali Hindus to India and Bengali Muslims to the newly created East Pakistan continued through 1951 (Hill et al., 2005). Consequently, the effect of partition is much more difficult to determine in North Bengal. Despite that, records suggest that over 15,000 immigrants flowed into Malda, West Bengal (Directorate of Census Operations 1951). These immigrants primarily came from Bihar, Odisha, Uttar Pradesh, and Nepal (Directorate of Census Operations 1951). This built economic pressure on Malda’s fertile alluvial soil. On the other hand, local women had little to no share in those activities, leading to a sense of resentment and anti-foreigner feeling among indigenous Rajbanshi community. Similar trends emerged from Jalpaiguri and West Dinajpur districts which lie close to the India-Bangladesh border (Saha 2018).

However, demographic uncertainties continued to transform North Bengal’s political landscape even after the Great Divide. For instance, no declaration was made to confirm the integration of Malda with either nation post-partition. Hence, Malda was under East Pakistani administration for three days until authorities finalised its inclusion with the Republic of India (Directorate of Census Operations 2011). The same happened with Dinajpur district. Further, a third of Rajshahi was included in India, strategically cutting off the northern part of North Bengal from roadways and railways from the rest of West Bengal. Cooch Behar, a quasi-independent state, signed the Instrument of Accession in 1949 and emerged as a new district in North Bengal (Islam 2010).

Liberation of Bangladesh (1971)

If 1947 transformed South Asia’s socio-political relationships, 1971 further complicated its geopolitical ones. The war preceding the liberation of Bangladesh in 1971 resulted in a massive inflow of both Hindus and Muslim immigrants from East Bengal. It brought dramatic demographic changes to the landscape with swathes of people migrating to West Bengal, especially North Bengal. The population in the region grew at 27.63%. This rate of growth was 4% more than the growth rate of the rest of the state (Table 1). According to Directorate of Census Operations (1951, 1961, 1971, 1981) data, 87,620 immigrants from erstwhile East Pakistan entered North Bengal during the decade 1961-71 (Table 1). This inflow fundamentally changed the geopolitical landscape of the region.

Table 1: Comparative table of growth rates of population in West Bengal and North Bengal in percentage

| Census Year | West Bengal | North Bengal |

| 1951-1961 | 32.80% | 40.49% |

| 1961-1971 | 26.87% | 33.01% |

| 1971-1981 | 23.17% | 27.63% |

Source: Directorate of Census Operations (1951, 1961, 1971, 1981)

Most numerically sparse tribes like Bhumijas began assimilating fully into the Hindu fold. The Bhumijas even forwent their indigenous language in favour of Standard Bangla. Moreover, land that was previously populated by indigenous communities came to be dominated by dominant caste Hindu immigrants (Saha 2018). This land occupation led to the creation of new functional, trading, and commercial classes in the economic sphere. The loss of indigenous employment and territory was supplemented by anti-foreigner sentiments and a growing feeling of alienation from their homeland. Hence, they formed the Uttar Banga Tapshili Jati o Adibashi Sangsthan to demand special government safeguards. This later became the Kamtapur Peoples Party [KPP] movement (Saha 2018).