CONTEXT

The COVID-19 pandemic has created unforeseen challenges in India’s educational landscape. Schools and colleges have switched to remote learning and started online classes and exams. The pattern of education has changed overnight, and digital learning has emerged as the primary alternative. This sudden switch and overdependence on technology has come with its fair share of constraints. Amidst this transition, for the first time in 34 years, the erstwhile Ministry of Human Resources and Development, now known as the Ministry of Education, launched the New Education Policy on 29th July 2020. Expectedly, the policy proposes several measures for promoting digital learning and enhancing infrastructure requirements. However, given the socio-economic and regional diversity of India, there exist multiple roadblocks to accessibility and the ability of widespread adoption of online teaching and learning, some of which are discussed in this commentary.

DIGITAL DIVIDE

Digital deprivation has been an ongoing issue in India even before the challenges brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic. The key problem surrounding remote learning and online classes in the country is the issue of equitable access. Along with adequate penetration of internet and technology services, accessibility in this context also includes access to electronic devices such as computers and smartphones.

According to NSSO data, only 4.4% of rural households and 23.4% of urban households own computers. Moreover, while 42% of urban households have a computer with an internet connection, the same is available to only 14.9% of rural households [1]. A report by Nielson in 2019 concluded that 70% of the rural population does not have an active internet facility with states like West Bengal, Bihar, Jharkhand and Odisha having the lowest internet penetration [2]. Especially in the northeastern states, the findings of the report indicate that users are less affluent and predominantly male. Remote learning has also been a challenge for students in the union territory of Jammu and Kashmir. The ongoing ban on 4G internet has been particularly challenging for students and teachers in the state with digital learning becoming the only option during the pandemic. It has been reported that the available 2G internet connectivity has led to unclear audio and frequent video call drops, among other problems [3].

There are approximately 500 million smartphone users in India as per a recent report by the Indian Cellular and Electronics Association (ICEA), which could reach 829 million by 2022 [4]. Increasing affordability of smartphones, growth in number of users in rural India, as well several government initiatives have led to the expansion of India’s smartphone user base in recent years [5]. However, on the other side of this growth is the fact that there are still around 800 million people that do not have access to smartphones. The audio-visual content in online learning, whether in the form of video calls or downloadable/streamable videos, requires high-speed 4G internet. As per the ICEA report quoted above, in 2018, India had approximately 277 million VoLTE capable devices and more than 50% 4G device penetration across India. However, the share of smartphone penetration was only around 25% in rural areas. Given that 99% of rural internet users access the internet on mobile phones, this effectively means that a majority of students in rural areas do not have the tools required to access online classes. Some of the worst consequences of the lack of smartphone penetration and 4G internet have been incidences of student suicides, seemingly in response to the inability to afford smart devices and the mounting pressure to attend online classes to keep up with coursework [6][7].

LITERACY GAP

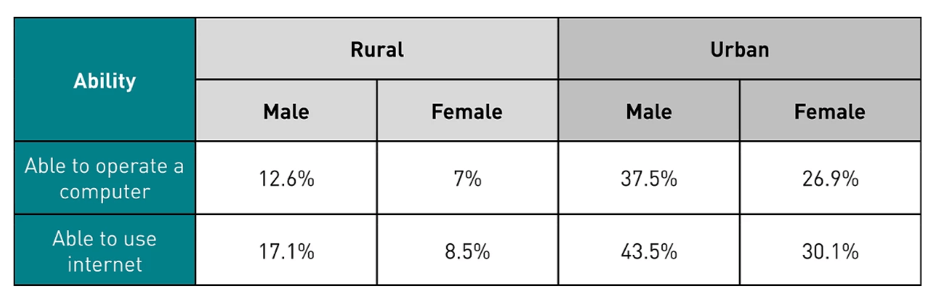

Along with a prevalent urban-rural divide, there also exists a deepening male-female digital literacy gap in India. Data from NSSO’s 75th round national survey (2017-2018) shows a significant gap between the male and female population in rural and urban areas with regard to the ability to operate a computer and use the internet. As shown in Table 1, only 8.5% of women in rural India are able to use the internet as compared to their male counterparts (17.1%). For urban areas, the percentage of users is significantly higher, but the gender gap remains [8].

Table 1: Share of persons able to operate computer and use the internet in India

Source: Ministry of Statistics and Programme Implementation 2019

Other micro-level studies also show similar findings. Aggarwal, in a study in the urban slums of Delhi, found that 90% of men had mobile phones out of which 59% had a smartphone, and 58% had internet connection on their phones. On the other hand, 58% of women had a phone, of whom 22% had a smartphone, and 18% had internet connectivity [9]. Another study in Aligarh found that 52.25% of male and 14.28% of female respondents owned smartphones. Moreover, none of the female respondents were able to download applications or knew about Google Play Store/any other app store [10].

This digital literacy divide among males and females is a key structural constraint in the proliferation of digital methods of learning that carries multiple negative impacts on women’s educational attainment, skill development and workforce participation.

IMPACT OF REMOTE LEARNING ON PUPILS AND TEACHERS

According to UNICEF, the closure of schools in 2020 has affected more than 1.5 billion children and young people worldwide, leading to a wide range of psychological and behavioural challenges. The increase in screen time not only impacts children physically but can also lead to heightened risk of online exploitation. The rise in the use of virtual platforms may expose young children to harmful virtual content which may also contribute to cyberbullying [11].

An online survey conducted among 155 students across 13 states in India showed that students often complained about frequent headaches and neck/back pains due to long online classes. The survey indicates that students are subjected to 5-10 hours of screen time in a day, which includes both school lessons as well as private coaching classes. Also, since 45% of students use headphones while attending lectures, there is an increased risk of developing hearing issues in addition to eye problems and musculoskeletal pains. Lockdown teaching has also restricted students to the sit-down method of learning and reduced their opportunities for extracurricular and physical activities [12].

Online learning has further proven to be a considerable challenge for students with disabilities. As per a phone-based survey of 387 students with disabilities conducted by the NGO Swabhiman in May 2020, 56.8% were found to be continuing their studies with the rest opting to drop out. Additionally, only 56.4% of those interviewed had access to personal or collectively used smartphones. The survey also found that deaf students, specifically, were struggling during webinars with multiple speakers and generally finding it difficult to lip-read on screens [13].

Notably, teachers are also at a high risk of being impacted both physically and mentally because of increase in online learning. Media reports indicate that virtual classrooms have made significant adverse impacts, particularly, on female teachers. Remote learning has led to an increase in bullying of female teachers by older students and have thrown up numerous incidents of violation of privacy of teachers [14][15].

CONCLUDING REMARKS: NEP 2020 AND BEYOND

The NEP 2020, taking cognizance of the present scenario of education in India, seeks to encourage “carefully designed and appropriately scaled pilot studies to determine how the benefits of online/digital education can be reaped while addressing or mitigating the downsides” [16].

As part of its recommendations for leveraging digital technology for learning, the NEP aims to build a new autonomous body – National Educational Technology Forum (NETF) – that will standardise the content and pedagogy, and promote adoption of continuously evolving technologies for digital learning nationwide. Some of the more tangible initiatives recommended by the NEP are:

- Extension of existing e-learning platforms like DIKSHA and SWAYAM to provide teachers with user-friendly assistive tools like two-way audio and two-way video for monitoring the progress of pupils [17][18].

- Development of a digital repository of coursework, simulations, game-based learning, augmented reality and virtual reality.

- Development of virtual labs using DIKSHA and SWAYAM, particularly, to make such programs accessible to students and teachers belonging to socio-economically disadvantaged groups through preloaded tablets.

- Provision of a new National Assessment Centre to design and implement new assessment frameworks that incorporate 21st century skills.

However, when it comes to addressing the digital divide as discussed previously, the NEP recommends use of television, radio and community radio for 24*7 broadcasts of educational programmes, including in regional languages [19]. Whether such programmes can replace online classes and e-learning tools, and provide the same quality of education to students who do not have access to smartphones or the internet is up for debate. Certainly, the NEP doesn’t seem to offer any specific recommendations to bridge the gender gap in digital literacy, nor does it directly address the physical and mental health consequences of online classes. It also doesn’t seek to cover issues faced by students with disabilities while accessing online learning methods.

It can be concluded that though the NEP offers some progressive initiatives for development of e-learning tools and seeks to encourage equal access to technology, it misses the mark when it comes to addressing the grave structural challenges that characterise digital learning in India. Going forward, it is imperative to bring about convergence between the goals of the NEP and flagship schemes like Digital India that seeks to expand access to communication infrastructure and internet connectivity across the country. A key focus, therein, has to be on bridging the gender gap in internet usage and access to smartphones, and simultaneously making digital learning disability-friendly.