Introduction

In this fast-paced world, fashion serves as a medium of self-expression, allowing individuals to showcase their personalities and ideologies through their styling choices. The choices made regarding clothing and accessories can establish a person’s social, political, and economic identity. Yet, as the world delves into this pursuit of authenticity and creativity in our appearances, there is a pressing issue we must confront—fast fashion.

Fast fashion refers to mass-produced, low-quality clothes inspired by latest trends, which are sold at a lower price point. Fast fashion perpetuates the fatuous idea that re-wearing outfits is a fashion error. Historically, people would keep their clothes until they wore out, but today, fast fashion has created a surge in consumption, with consumers buying more and frequently discarding older clothes. The accelerating growth of fast fashion raises concerns about sustainability and the true cost of our style.

On another note, people are becoming increasingly aware of the consequences of fast fashion and are inclining towards sustainability. This growing emphasis on sustainability was also showcased in the London Fashion Week, with all brands following the Copenhagen Fashion Week’s sustainability requirements adopted by the British Fashion Council. This is a step towards creating the fashion industry as a more sustainable and responsible industry.

To make headway toward sustainability producing garments in a sustainable manner is not enough. There is a need to efficiently manage the waste generated from the textile and apparel industry. In India, the textile sector provides employment to over 45 million people and produces about 22,000 million pieces of clothing per year, with the market size projected to reach $350 billion by 2030. With such a huge industry, it is integral to take measures to reduce the negative impact on the environment.

Textile Waste Crisis in India

Textile waste refers to the material that gets rendered useless or loses its worth after making any textile product. This wastage accumulates at every stage of textile manufacturing, from spinning and weaving to knitting, dyeing, finishing, and ultimately, clothing production. The issue of textile wastage poses a significant challenge, not only to the sustainability of the textile industry but also to the environment. For instance, in a dyeing facility, an alarming volume of wastewater is produced as large quantities of fabric undergo coloring, creating a serious environmental hazard that cannot be overlooked.

According to a report, 8.5% of global textile waste is accumulated in India annually through waste generation or imports. Textile waste in India can be compartmentalised into three waste categories: domestic post-consumer (51% of the total waste), pre-consumer (42% of the total waste), and imported post-consumer (7% of the total waste). Domestic post-consumer waste consists of reusable and non-reusable components, generated at the end of an apparel or textile’s use by consumers. It is the largest contributor to the total waste generated in the country, with 3,943.3 kilotons discarded annually. Pre-consumer waste accounts for 3265 kilotons per year. It includes spinning waste (46%), mill waste (18%), readymade garments waste (24%), fabric deadstock (6%), and unsold garment inventory (5%). Imported textile waste forms 7% of total textile waste and falls within two categories- mutilated rags (32%) and second-hand clothing (69%).

India has a long-standing tradition of sustainable practices wherein individual as well as community efforts have been undertaken. Lower and middle class households in India buy clothes occasionally and with the intent to use them long term. They are carefully maintained, and even after fulfilling their intended purpose, the cloth is utilised to its fullest by either being donated, passed down to younger family members, or converted into a cleaning rag. Traditionally, many households even upcycled old garments using various techniques. For instance, in West Bengal, women would use old saris or dhotis to create layered fabric designs. They would embroider these layers with multi-colored threads and patterns, incorporating motifs inspired by their daily life and culture, also known as Kantha embroidery. Sujani is an age-old technique of Bihar that was associated with needlework. Sujani is similar to Kantha embroidery, but sometimes Sujani fabric is much broader and coloured. Similarly, such practices could be noticed in most states of India.

However, these eco-friendly habits have taken a turn. Earlier, the clothes were made with pure cotton or silk and dyed with natural dyes. They were expensive to manufacture and had a high price, so they were bought sporadically and maintained well. With technological advancements, an increase in disposable income and a decrease in garment costs, people have started to consume and waste even more. Now, most clothes are made of blended fabrics and synthetic dyes. They are cheap and expendable.

Circular Textile Economy

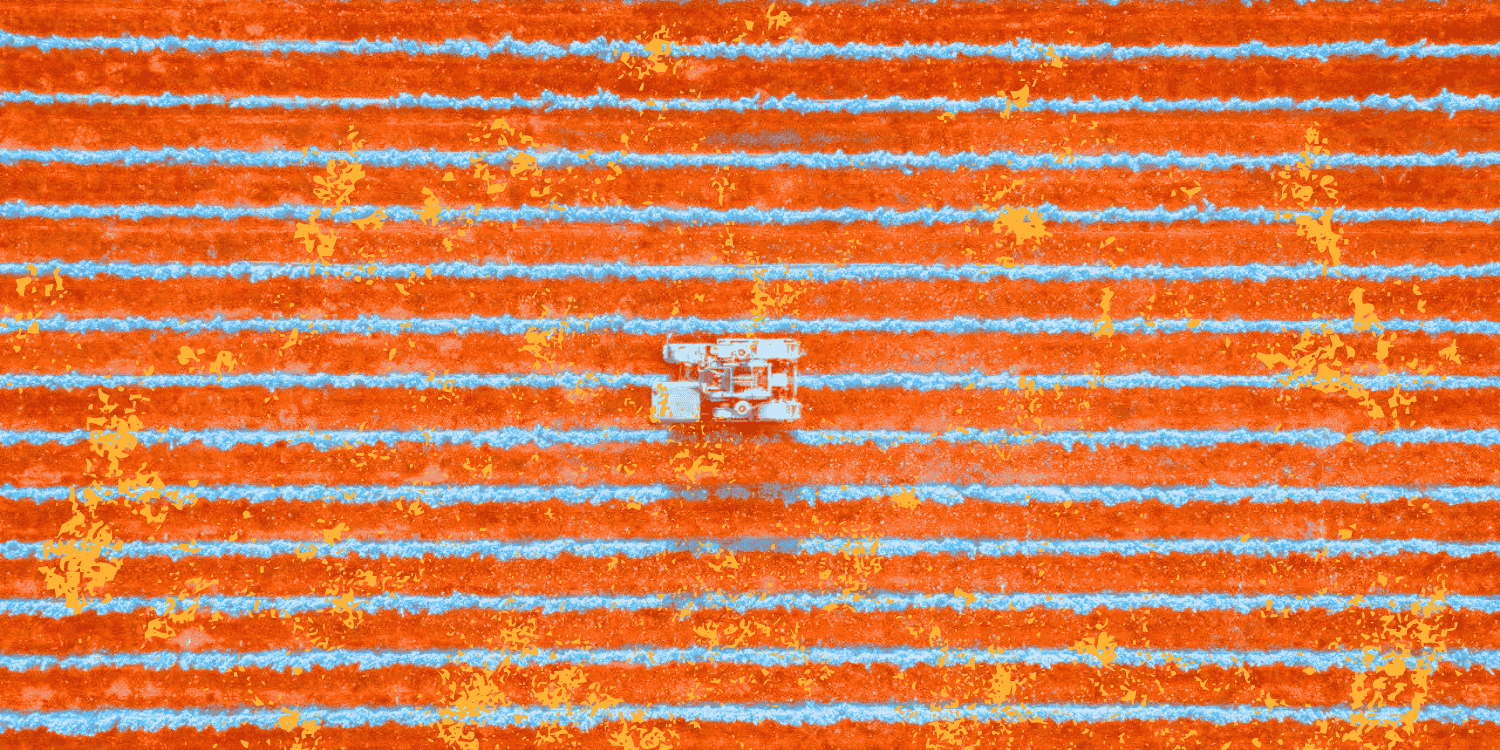

The circular economy is a model of production and consumption, wherein when a product reaches the end of its life, its materials are retained as much as possible to maximise their reuse and create additional value. To establish a circular textile economy (CTE), we could recycle, reuse, repair, and/or rent our clothes. A CTE links agriculture, textile, and garment sectors with each other. Cotton exemplifies this loop, starting with sustainable cotton farming, progressing to textile production using recycled fibers, and resulting in recyclable clothes.

According to a report, it was noted that to create a CTE, one should target phasing out harmful substances from the manufacturing process, transforming the way clothes are designed, sold, and used, so they escape their disposable character, improving recycling by revolutionalising clothing design, collection, and reprocessing, and effectively utilising resources and shifting to renewable inputs.

A CTE has significant benefits. Firstly, it would lower the costs of manufacturing high-quality, sustainable clothes and reduce the need for raw materials as recyclable fibres would be used. This would benefit the businesses, the customers, and the environment. Second, introducing new rental and subscription models would allow fashion brands to create profits without having to increase throughput, and open up opportunities for innovators to trial new business models. Third, the idea of circularity focuses on creating clothing designed to stay valuable over time, leading to better materials, processes, and services. Fourth, a new textile economy would significantly reduce greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions as the durable and recyclable nature of the clothes would increase wear. Using low-carbon materials and production processes would further reduce the GHG emissions. Fifth, the environment would benefit from the sustainable and clean process of manufacturing leading to reduced land and water pollution. Lastly, in such an economy, safe and healthy material inputs into textile production would not leave workers exposed to substances hazardous to their health and would reduce health risks for everyone wearing clothes.

An assessment report on CTE in India found textile circularity to still be in its early stages. Several institutions such as IIT (Indian Institution of Technology) Delhi, NIFT (National Institute of Fashion Technology), NID (National Institution of Design), etc. have introduced courses and programmes for promoting sustainability in the fashion industry. Fibre and yarn waste mapping revealed that while circularity practices exist, challenges persist. Dyed yarn weaving generates coloured selvage waste, reducing recyclability, while sized fabric contributes to increased water consumption through weight-based pricing. Loom waste varies, with handlooms and power looms producing none, whereas rapier, airjet, and waterjet looms produce selvage waste in various manners. The apparel industry is embracing circularity, with cutting waste constituting a large proportion of textile waste. The majority of the cutting waste, though, is being sold in mixed form, thus restricting recyclability. A semi-organised recycling process exists—small waste is used for recycled fibres, medium waste for kidswear, and large waste for low-cost garments. Waste collectors sort and provide waste for recycling, but use low-quality fibre blended with virgin fibre. Denim and woven apparel manufacturers in Bengaluru have implemented Zero Liquid Discharge (ZLD) technology for wastewater recycling. Newer generations are interested in sustainability and willing to pay a premium. To support the circular economy, brands are also adopting eco-friendly packaging to reduce plastic use.

While attempts are being made to formulate a CTE, roadblocks in the journey continue to persist. Industries are either not keen or unable to invest in sustainable technologies because they lack the capital to invest in advanced technology and processes. There is a lack of adequate infrastructure to support the implementation of sustainable and circular production techniques and practices. The use of obsolete technology, the difficulty of separating various types of fibres, and the lack of waste management infrastructure make it challenging for the sector to recycle and reuse materials successfully. Existing regulations only support sustainability components to a limited degree, while circularity is not yet addressed. There is a need for research and development to adapt to new technologies.

To form a CTE, all sections have to take necessary measures. Brands and manufacturers should be more conscious of the material they use, the waste they generate and how they dispose of it, the wages they pay, and the packaging they use. Consumers should be mindful of environmental impact by buying only what’s needed from eco-friendly brands.

Policy Initiatives

A CTE strategy can be formed in India by taking inspiration from the European Union (EU) strategy. The EU strategy includes developing product-specific eco-design standards to enhance textiles’ performance in terms of durability, reusability, reparability, fibre-to-fibre recyclability, and mandatory recycled fibre content, to track the presence of substances of concern, and to reduce the adverse impacts. The strategy also seeks to prevent the dumping of unsold or old stock in waste, ultimately reducing textile waste. According to the European Environment Agency, textile waste dumping decreased from 21% (220,000 tonnes) in 2010 to 11% (150,000 tonnes) in 2020. Simultaneously, energy generation from textile waste increased from 9% (90,000 tonnes) in 2010 to 16% (220,000 tonnes) in 2020.

A study estimated that 13 million tonnes of coastal synthetic fabric waste enters the ocean each year. It was anticipated that 1.5 million trillion microfibers are present in the ocean. Microfiber pollution is a serious threat to aquatic ecosystems and needs to be mitigated. Policies should focus on eliminating substances identified as the highest concern and incentivising the use of recycled fabrics. This can be done by banning the use of such products or imposing high tariffs on the use of such substances.

The government could introduce Extending Producer Responsibility (EPR) schemes for textiles, obliging clothing companies to contribute to the recycling and waste management of the clothes they put on the market. All EU states have a requirement to implement EPR schemes. For instance, in France, the EPR scheme was introduced in 2007 and applies to any company selling products on the French market. While some companies have implemented custom take-back programs, nearly all others utilise the Refashion collective compliance scheme, which operates a network of textile collection points throughout the country.

Subsidies for start-ups or brands focussing on creating recycled and sustainable clothing could encourage more organisations to go green. Concentrating infrastructure investments on systems for collecting, sorting, and reprocessing materials could aid in the sustainable movement. Public-private joint ventures for research and development programmes could reduce the burden on each party, and facilitate forming a CTE.

Governments could provide incentives, regulatory frameworks, and infrastructure to NGOs for awareness campaigns, community engagement programs, and upcycling initiatives. NGOs could also partner up with brands to set up collection points for used clothing, recycle donated clothes, and facilitate small projects for upcycling clothes. In India, Goonj is an NGO working on promoting sustainability through its Green by Goonj initiative.

In 2019, the then Union Minister for Textiles, Smriti Irani launched ‘Project SU.RE’ as a step towards encouraging sustainability in the fashion industry. Thirty prominent fashion companies in India committed to sourcing or using significant proportions of their entire consumption using sustainable raw materials by 2025. Since its launch, SU.RE has hosted roundtables, including the latest in January 2025, partnered with the British Council, conducted MSME sustainability assessments, contributed to the Global Fashion Summit, and worked on textile recycling with Fashion For Good. However, as pointed out in an earlier discussion paper by Sitara Srinivas, efforts must also be focussed on regulating the cotton industry, which contributes significantly to the textile sector in India.

Conclusion

India needs to take steps towards increasing the circularity of the textile industry for sustainable and long-lasting growth of the sector. This includes reducing waste, increasing recycling, and adopting eco-friendly measures for textile production. Being the second largest clothes manufacturer, India has great potential to drive sustainability in the global textile industry. Though the trend of sustainable fashion is increasing among the younger generations, the customer demand is still low. Unlike the West, sustainability is not an Environmental, Social, and Governance (ESG) priority in India. This begets the question of how sustainability could be incorporated when much of the domestic market is catered to by the informal sector which lacks the means and incentives. There is a need to organise the informal sector and equip them with financial support to promote sustainability.

However, only government efforts are not enough, brands and consumers should also conscientiously follow sustainable patterns. Brands need to integrate sustainability into their supply chains, invest in innovative materials, and commit to ethical manufacturing. At the same time, consumers should make mindful purchases, support sustainable brands, and actively recycle and reuse old clothes.