Introduction

During the 1980s and 90s, Bihar’s economy experienced a profound crisis. While most states were witnessing positive growth in their Gross State Domestic Product (GSDP) and per capita income, Bihar, in contrast, exhibited negative growth rates in these two areas. It cemented its place as the poorest state in India, despite being blessed with rich resources of land, labour, and water. Across all indicators, including Head Count Ratio, agricultural productivity, urbanisation, and literacy rates, Bihar consistently demonstrated patterns of chronic underperformance. These trends positioned Bihar among the lowest-performing states in the nation (Joseph, 2007).

Being given the unfortunate tag of a ‘BIMARU’ on account of its underprivileged status as a low development state, Bihar has seen a positive trend of growth since 2005 (Kumar, 2020). An increased share of the service sector and rapid investments in development projects have been at the core of the rising growth front for the region, in the decade after the formation of thet Nitish Kumar government.

Even in the post-Covid period, Bihar registered a notable recovery, recording a growth rate of 10.98% in its GSDP for 2021-22, which was the third highest highest amongst all states in India (Bihar Economic Survey 2022-23). The Economic Survey also noted increases in per capita GDP for the state, and estimated a growth rate of 9.3% in 2021-22, at constant (2011-12) prices. The GDP and per capita growth rate, while not complete estimates of the health of an economy, certainly do stand as positive indicators of its growth.

Structural growth and transformation in Bihar is also another aspect that deserves an inquiry. Marjanovic (2015) outlines that the core concept of structural transformation involves not only the accumulation of physical and human capital but also shifts in demand, production, employment, and trade composition. Structural transformation, according to him, encompasses major economic phenomena such as industrialization, agricultural transformation, migrations, and urbanisation. These processes involve a mutually influential relationship between rising incomes and alterations in supply and demand proportions, all influenced by macroeconomic and sectoral policies. The traces of this structural transformation can be seen in the trends of development for Bihar’s economy, where mainly the primary and tertiary sectors have observed high growth rates in recent years, as compared to the national average. It must be noted that while the share of the tertiary sector in the Gross State Value Added (GSVA) has been increased substantially, now holding the highest share of GSVA in the economy, the Economic Survey of Bihar in 2023 also states that this development has not yet been accompanied by the expected phenomenon of rural to urban migration.

One of the main goals of this paper is to understand the current employment scenario of Bihar and assert the trends observed in the state and find the root factors involved. Dr. Ajad Singh and Menka Singh (2023) analyse the trends of unemployment in Bihar, referencing various rounds of NSSO household data on ‘Employment-Unemployment’, which covers various employment and unemployment dimensions.

Bihar’s male unemployment rates are typically higher in rural areas, except for a spike in 2017-18. Based on their findings, male unemployment has generally decreased over time. However, rural areas consistently experience higher rates of unemployment compared to urban areas, except for the period of 2017-18, when female unemployment rates were also elevated in urban areas. Bihar’s unemployment rate has decreased, but it remains higher than the national average and among males. Within the scope of this paper, the structure of unemployment in Bihar will be examined, along with an assessment of state-led improvements and the future potential for addressing this issue.

Tracing Bihar’s Developmental Track: Pre-2004

The post-liberalisation growth that was observed by the western states of Punjab, Maharashtra, and Gujarat was a phenomenon that did not extend to the relatively resource-rich states of Bihar and Uttar Pradesh. Bihar’s development continues to be plagued by factors that are linked to the mass migration observed in the state.

Agrarian Employment Structure in Bihar

According to the 2001 Census, a substantial portion, exceeding 77%, of Bihar’s population was engaged in agricultural activities, either as cultivators or labourers. Furthermore, the proportion of agricultural labourers surpassed that of cultivators across Bihar and in most districts in the state. Given the limited development in industrial and tertiary sectors during this period, agriculture emerged as the primary source of livelihood for a majority of households in Bihar. Agriculture was also the largest contributor to the net state domestic product share, with 43.7% in 1998-199 (Joseph, 2007). While the majority of the population was engaged in agriculture, in particular the rural poor, the share of income contribution of the sector to the state was disproportionate, signifying an unhealthy dependence on the same and inadequate production in the industry, which contributes to pervasive poverty and low living conditions for individuals who depend on agriculture. A considerable portion of the population makes their living in a low-income industry, which widens the gap between the rich and the poor, exacerbating income inequality.

An over-reliance on agriculture inhibits economic growth and diversification by restricting development in more productive sectors like manufacturing and services. It also renders the economy susceptible to shocks from the environment and the market. This reliance also makes it more difficult to invest in infrastructure, technology, and education, which stifles innovation and slows down economic growth overall. Low agricultural income can therefore prevent people from developing to their full potential and prolong poverty cycles by limiting their access to healthcare, education, and other necessities.

Joseph notes the distinction between free labour and unfree labour in the context of Bihar. Under the tenets of Marxian thought, free labour is described as an ideal scenario where the labourer is neither bonded to the landowner or to any means of production, i.e, they have ownership over their means of labour, which may be sold to the highest bidder. In this case, the existence of ‘extra economic’ factors prevent the realisation of free labour for the rural economy. The extra economic factors here may be socio-political factors or the lack of sustainable alternatives.

This sense of free labour was inherently lacking for agricultural labour in Bihar, due to the nature of relations of the labourer with land in rural areas, where landlessness is a major contributor to the level of precarity or exploitation that a person experiences in the region. Similar patterns were noted in the state of West Bengal too, where landlessness was linked to a higher incidence of poverty. Joseph also underlined that the lack of non-farm sector in rural Bihar also becomes a huge contributor to the culmination of unfree labour in this region.

High Population but Low Skill

One of the major challenges Bihar faces is its high population density coupled with a heavy reliance on agriculture for employment. This is compounded by the lack of a robust non-farm sector in the region. Post liberalisation, the percentage employed by the agriculture sector went from 41.8% of the economically active population in 1971 to 48% in 2001. To note importantly, the proportion of agricultural workers in the overall workforce for India reduced during the same period, from 31.4% to 26.5% (Rasul, 2014).

For Bihar, the majority of labour employed in agriculture is limited to unskilled workers, due to the lack of government investment into vocational training and education. Misguided policies like the Direct Benefit Transfer (DBT) scheme, for example, have failed to effectively implement education for children. According to a survey from Jan Jagran Shakti Sangathan (JJSS), most funds from these DBT funds meant for student needs were instead directed towards basic sustenance, defeating the purpose of the scheme. Additionally, a lack of a strong response from the government to the educational deficit created by the COVID-19 pandemic has further exacerbated the problem in recent times. Furthermore, the ASER 2022 report indicates that almost 87% of grade 3 students, 63% of grade 5 students, and 30% of grade 8 students are unable to read at a grade 2 level. This demonstrates that, despite high enrolment rates and the appearance of widespread elementary education, many children in Bihar are not receiving quality education in government schools and cannot afford private tutoring (Sharma & Amitava, 2024). Moreover, a significant portion of land is held by landlords, and agriculture is mostly worked by peasants who owe portions of their harvest to these landlords. A prevailing low savings rate amongst the small farmers has led to a lack of incentive to invest in agriculture, leading to a stagnating agriculture sector that cannot absorb employment. The lack of a non-farm sector in this case also eventually led to workers being forced to migrate in order to seek employment.

Accounting for Wage Differentials

Arjan De Haan (2010), in his study into the history of migratory patterns in Bihar, notes a significant wage differential between Bihar and other states of India emerging from the 1960s and persisting all the way into 1990s, which has been identified as a key factor in the decision to migrate. A key point to note is that even today, migration is a pattern that is not limited to castes and classes in Bihar, where overall migration has been noted to be high across all these categories. The marginalised and impoverished sections of society, namely the SC/ST and parts of the OBC community, have been observed to have a higher likelihood of migrating, more in recent times as the availability of transportation was made more accessible.

Post-2004 Bihar

In terms of Structural Change

Post-2004 Bihar has seen significant improvement in terms of growth measured in terms of the Gross State Domestic Product (GSDP). The Compound Annual Growth Rate (CAGR) for the GSDP of Bihar has kept an average of 8.22% from 2004 up until 2017. This growth has mainly been the result of progression in the secondary and tertiary sectors of the economy, with the share of GSDP contributed increasing consistently over this decade.

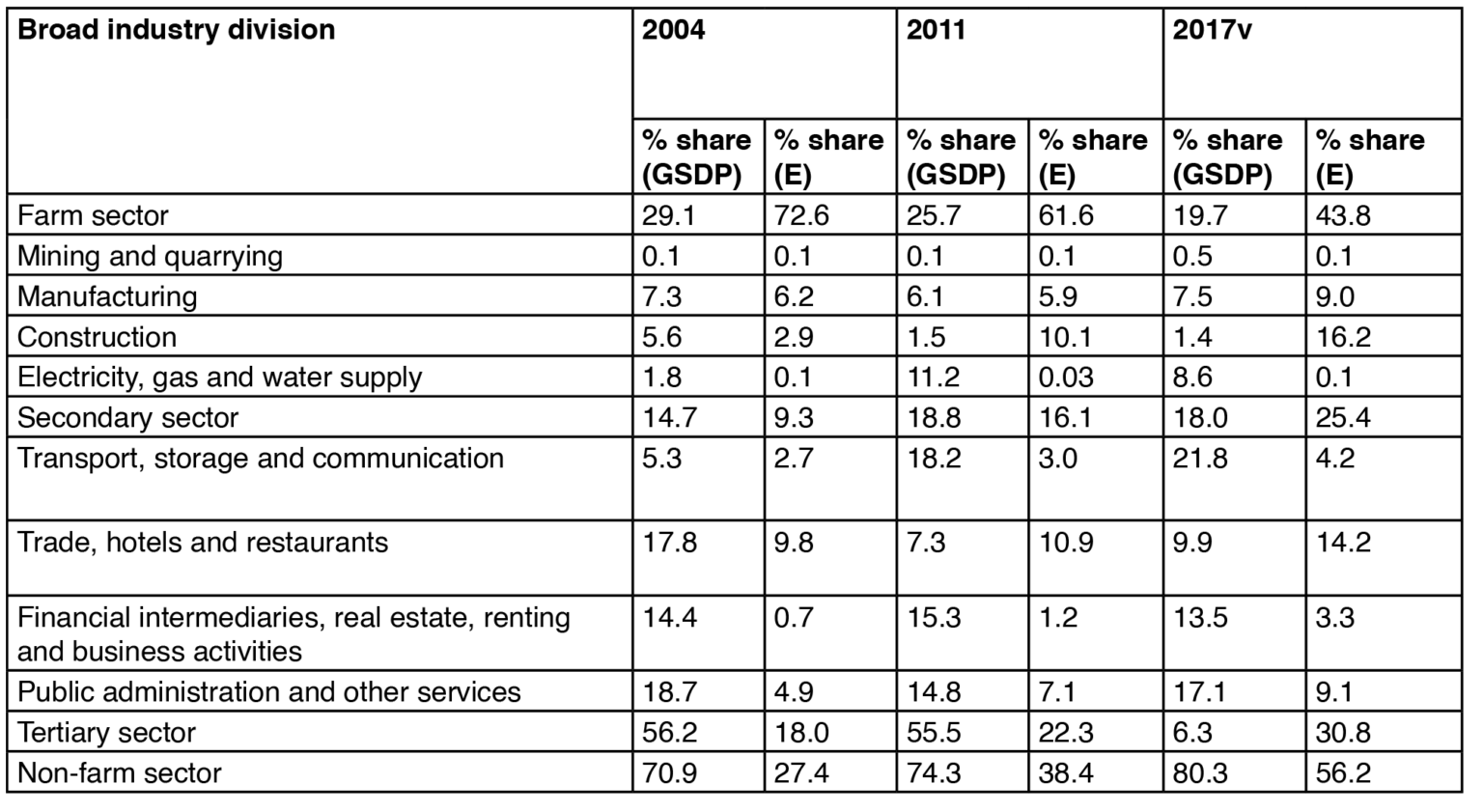

While there still exists a gap between the shares of income versus the proportion of employment generated for these three sectors, the state of Bihar has shown a positive trend in improving the scope of employment generated by the secondary and tertiary sectors, in comparison to pre-2004 periods where the agriculture was almost the exclusive employer for a majority of the population. For example, in Figure 2, if we look at the tertiary sector, there has been a consistent increase noted in the share of employment generated for the economy across 2004, 2011 and 2017, going at 18%, 22.3% and 30.8% respectively. Consequently, the sector has seen dips in the share of employment, going from 72.6% in 2004, to 43.8% in 2017. The secondary sector has also seen improvements in its employment share over the years, but interestingly the growth in terms of GSDP share has stagnated after 2011. Kumar (2020) highlights that within the secondary sector, construction made a significant contribution, surpassing 50% in 2018-19. This represents a substantial increase from 17.15% to 51.02%, marking a 197% rise with an average growth rate of 13% per annum. The diminishing shares of the manufacturing, electricity, and gas and water supply sub-sectors within the secondary sector is what Kumar raises concerns about, noting the slow industrial growth in the state.

Source: The Indian Journal of Labour Economics (2020)

However, this does not imply that Bihar’s additional growth trajectory is perfect by any means, in terms of employment. A big factor to consider is the high unemployment rate that still persists within the economy. In light of more recent numbers, the data from the PLFS indicates a significant rise in Bihar’s unemployment rate. The state’s unemployment rate increased from 4.6% in 2020-21 to 5.9% in 2021-22. The state continues to have a high percentage of the population employed in agriculture, with a lack of significant job creation in other sectors; the recent 2022-23 Economic Survey notes that the state continues to rely on agriculture and allied sectors as an integral part of the economy. Replacing agriculture as the central source of employment is one of the bigger goals that Bihar is yet to achieve.

Current Employment Scenario

When examining Bihar’s male demographic, a consistent pattern emerges where rural areas typically exhibit higher unemployment rates compared to urban areas, except for a spike in 2017-18 affecting both regions. In 2021-22, rural unemployment stood at 63 per thousand versus 45 per thousand in urban settings. In the context of unemployment, the “per thousand” metric refers to the number of unemployed individuals per 1,000 people in the workforce. It’s a way of expressing the unemployment rate as a proportion of the labour force, measured as the number of unemployed individuals divided by the total labour force.

They note an overall downward trajectory in male unemployment in Bihar, except for a slight upturn between 2011-12 and 2017-18. For females in Bihar, urban areas generally face markedly higher unemployment rates, barring 2017-18. In 2021-22, rural areas recorded a rate of 19 per thousand, while urban areas reported 24 per thousand. Despite a significant rise between 2011-12 and 2017-18, they observe an overall decrease in female unemployment over time. Analysing data for both genders combined, they find a parallel urban-rural divide, with 2021-22 figures showing 58 per thousand in rural areas and 38 per thousand in urban areas. Overall, the combined gender unemployment rate in Bihar has shown a declining trend, except for a slight increase between 2011-12 and 2017-18. In comparison to the national rate, they argue that Bihar has consistently exhibited higher unemployment rates, albeit with a narrowing gap over time, particularly among males and both genders combined (Singh & Singh, 2023).

Female Employment Rate in Bihar

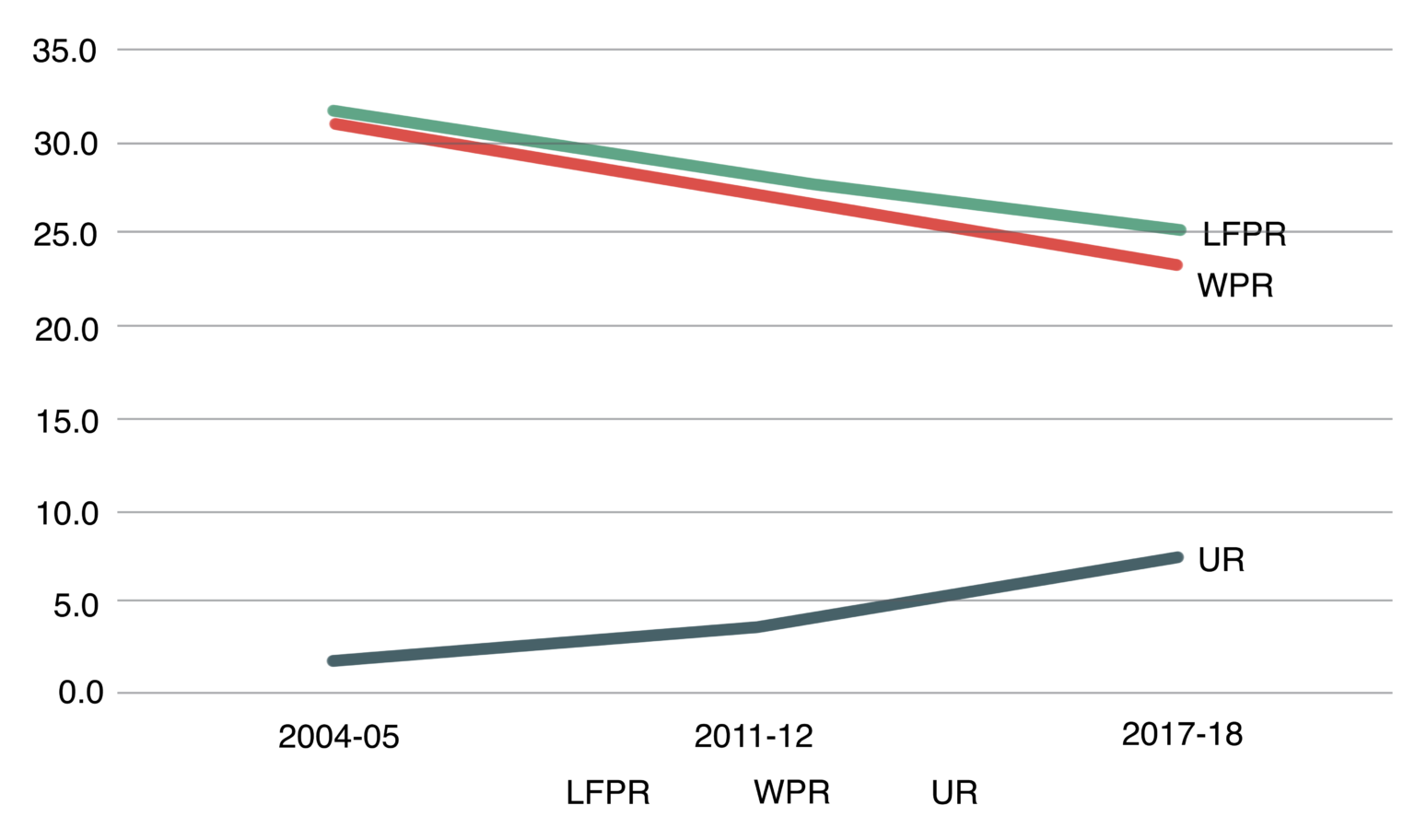

The trends of unemployment, particularly Labour Force Participation Rates (LFPR), for females in Bihar is markedly distinct from the male population, and these trends hold relevance as they reflect the availability of employment in the state as well. Sabreen (2020) notes that while unemployment rates decreased by 5% for females between 2011 and 2017, the unemployment rate for males increased during the same period. However, when it comes to the LFPR from 2004-05 to 2017-18, there was over a 10% decline. Remarkably, in the 2017-18, the participation rate of females in the labour force stood at a mere 2.6%, a notable contrast to the 45.3% observed among rural males.

Figure 1: Unemployment rate, Worker Population Ratio and Labour Force Participation Rate in 2004-05, 2011-12 and 2017-18

Source: The Indian Journal of Labour Economics (2020)

However, recent data stemming from the PLFS survey conducted during 2022-23 reveal a significant improvement in the female labour force participation rate (LFPR) compared to statistics from 2017-18. Presently, the LFPR for females stands at 22.4% in both rural and urban areas combined. Nonetheless, this figure remains starkly disparate when juxtaposed with the male LFPR, which registers at 74.6%.

Figure 2: LFPR for male and female, 2017-2023

Source: Compiled using data from PLFS data from 2017-23

Curiously, the survey indicates a lower unemployment rate among females, recorded at 1.6% for both rural and urban regions, in contrast to the male unemployment rate of 4.6%. Notably, urban areas exhibit a higher unemployment rate among females at 9.8%, surpassing that of males at 7.4%. Conversely, rural female unemployment stands notably lower at 1.1%. This may reflect a lack of skills available for women to pursue more skilled and higher-earning occupations, which will come to be more apparent with further observations. This is corroborated to an extent by the Bihar Economic Survey of 2023, which notes the distinct lack of female participation in the secondary and tertiary sectors. The distribution of female workers across the primary, secondary, and tertiary sectors is delineated as 77.7%, 5.8%, and 16.5%, respectively, in accordance with the findings of the survey. In contrast, male workers exhibit a distinct distribution pattern, with percentages standing at 43.5%, 27.5%, and 29% across the primary, secondary, and tertiary sectors, respectively. This notable contrast underscores discernible disparities in sectoral employment patterns between genders. Markedly, in Bihar, female participation in agriculture is among the highest, but neighbouring states like Jharkhand, West Bengal and Uttar Pradesh have all done marginally or significantly better in terms of assimilating women into the secondary and tertiary sectors.

Level of Urbanisation

As per the Bihar Economic Survey, the growth of urbanisation in Bihar has been critically slow, with the state only observing a decadal increase of 1.8% from 1961 to 2022, going from 7.4% to a projected 16.2%. The majority of this growth in the urban economy has also been observed after 2004, with the last official records of the urban population and level of urbanisation dating all the way back to 2011, as the new census has yet to be released. The projections from the survey, though, estimate that the urban population had to have risen to 20.2% in 2022. The state sees a skewed level of urbanisation across the Northern and Southern portions of Bihar, as declared by the Department of Urban Development and Housing of the state government, the major hubs of urbanisation being the Patna district, Munger and Nalanda. All three districts are located in the Southern parts of Bihar.

In the context of earlier sections, the level of urbanisation is crucial for a faster transition of the rural economy into the urban spaces of the tertiary sector, where there has been a disproportionate growth of GSDP and employment. Although the trends in structural growth have been positive, the rate of growth still leaves a lot to be desired in terms of the growth of the per capita income in Bihar and employment generation.

Future Growth

Improvements in the Non-Farm Sector

Gurpreet Singh (2020) observes that rural non-farm employment has been perceived as a feasible strategy for adaptation amidst challenges such as agrarian crisis, climate change-induced disruptions, and market failures. Households involved in non-farm activities demonstrate a higher capacity to withstand agrarian crises and maintain a more stable livelihood compared to those reliant solely on agricultural income. Singh notes that there are two scenarios where diversification into non-farm employment may occur: as a push factor when the agricultural sector is not performing adequately and as a pull factor when there is an expected increase in employment and wage rates. The evidence presented in this paper relating to disproportionate employment in the agricultural sector, and the positive although limited structural transformation of Bihar’s economy suggests that the first scenario presented by Singh may hold more relevance to the Bihar case here.

Sabreen (2021) notes that employment in the agricultural sector experienced growth between 2017-18 and 2018-19, whereas a decline was observed in the non-farm sector. This shift may be attributed to the limited job opportunities in the non-farm sector, prompting individuals in rural areas to engage more in agricultural activities. Similarly in her other work Sabreen (2020) noted that the insufficient level of skills and education among female workers results in their higher participation in the agricultural sector compared to the non-farm sector. Additionally, it is highlighted that the significant migration of male labour has created strain in local labour markets, consequently leading to increased female participation in the workforce, albeit predominantly in the agricultural sector.

Conclusively, while Bihar has structurally been transitioning into more of an urban economy, there needs to be a simultaneous focus on the non-farm sector in the rural economy, when the agricultural sector has already been struggling in terms of per capita income.

Initiatives in Skilling

The pandemic set into reality the acuteness of the skilling problem in Bihar, with lakhs of migrants returning to their home state and consequently facing unemployment on a massive scale. Prasad (2024) highlighted the key observation after the migration of nearly 50 lakh migrants back into Bihar during COVID-19;

The educational attainment levels of those who are 15 years of age and older. The percentage of people who are illiterate in Bihar is about 20.1 per cent in both rural and urban areas, while 12.6 per cent have only completed primary education. Furthermore, 15.8% of the population has completed school up to the middle level, while 17.4% has finished education up to the secondary level. As a result, in both rural and urban areas, about 20.1 per cent of people are illiterate and 45.8 per cent are literate but have not completed higher secondary education. Consequently, this statistic also plays into the composition of the migrants that leave in search of primarily semi-skilled or unskilled jobs in Delhi, Punjab and Harayana. Following the onset of the pandemic, a large number of unskilled and semi-skilled workers returned to Bihar. However, with the majority of work available during COVID-19 facilitated through ICT, these migrants and Bihar in general saw a huge wave of unemployment.

The key takeaway thus, becomes the necessity of the Government to devote more resources towards skilling initiatives to facilitate the entry into more skilled labour for both rural and urban populations. This may not only improve the transformation of the economy that Bihar is currently undergoing, but also provide incentive for curbing the large-scale out-migration observed in Bihar.

Conclusion

In summary, Bihar’s developmental trajectory presents a complex narrative spanning decades, characterised by both persistent challenges and notable progress. The state’s economy, once marred by chronic underperformance and labelled as one of the ‘BIMARU’ states, has undergone significant transformations since the early 2000s, driven by structural shifts and policy interventions.

Historically, Bihar’s economy was heavily reliant on agriculture, with a large portion of its population engaged in agrarian activities. However, this over-reliance on agriculture, coupled with a lack of investment in other sectors, contributed to stagnation and limited opportunities for economic advancement. The prevalence of ‘unfree labour’ in the agrarian sector further exacerbated inequalities and hindered the realisation of true economic potential.

The post-liberalization era witnessed some improvement, particularly in the secondary and tertiary sectors, leading to a more diversified economic landscape. However, challenges such as high population density, low skill levels, and wage differentials persisted, contributing to a cycle of poverty and migration. While the growth of the secondary and tertiary sectors offered some relief, the benefits were not equally distributed, with certain segments of the population, particularly women, facing barriers to participation in higher-skilled occupations.

In recent years, there have been encouraging signs of progress, with Bihar registering significant growth rates in its Gross State Domestic Product (GSDP) and per capita income. Structural transformations have played a crucial role in driving this growth, with the service sector emerging as a key contributor. However, challenges remain, particularly in addressing the persistent issue of unemployment, especially among rural populations and women.

Efforts to tackle these challenges must be multifaceted, encompassing investments in education and skill development, targeted policies to promote inclusive growth, and measures to address gender disparities in the labour market. Furthermore, there is a need for greater emphasis on creating opportunities for rural livelihoods and fostering entrepreneurship to reduce dependency on agriculture.

The sectors that needed to be worked through have also been identified i.e focusing on out-migration and skilling initiatives in the state. Rural non-farm employment is crucial for Bihar’s adaptation to agrarian crisis and market failures. Limited job opportunities outside agriculture lead to predominance of female participation in agriculture. There’s a need to bolster the rural non-farm sector alongside the struggling agricultural sector. Additionally, skilling initiatives are essential to address unemployment and facilitate the transition to more skilled labour, which could aid Bihar’s economic transformation and deter large-scale out-migration.