Author: Devi Divija Singal Reddy

Editors: Riya Singh Rathore

Water Seekers’ Fellow 2021 – SPRF India and Living Waters Museum

Hand hygiene is a simple and cost-effective way to prevent the spread of infections. Besides physical distancing and wearing masks, it is one of the public’s best defences during a pandemic. Since a healthcare facility is a high-risk setting, hand washing facilities for patients and visitors alongside healthcare personnel become a critical prevention tool. It acts as a control measure against COVID-19 and other healthcare-associated infections. However, there is limited available data on hand hygiene infrastructure from a beneficiary perspective in India. Most of the existing information is regarding essential hand hygiene services at points-of-care and hand hygiene compliance by healthcare providers. Further, there are no studies on current developments in hand hygiene infrastructure in hospitals from the standpoint of patients and visitors during the ongoing pandemic.

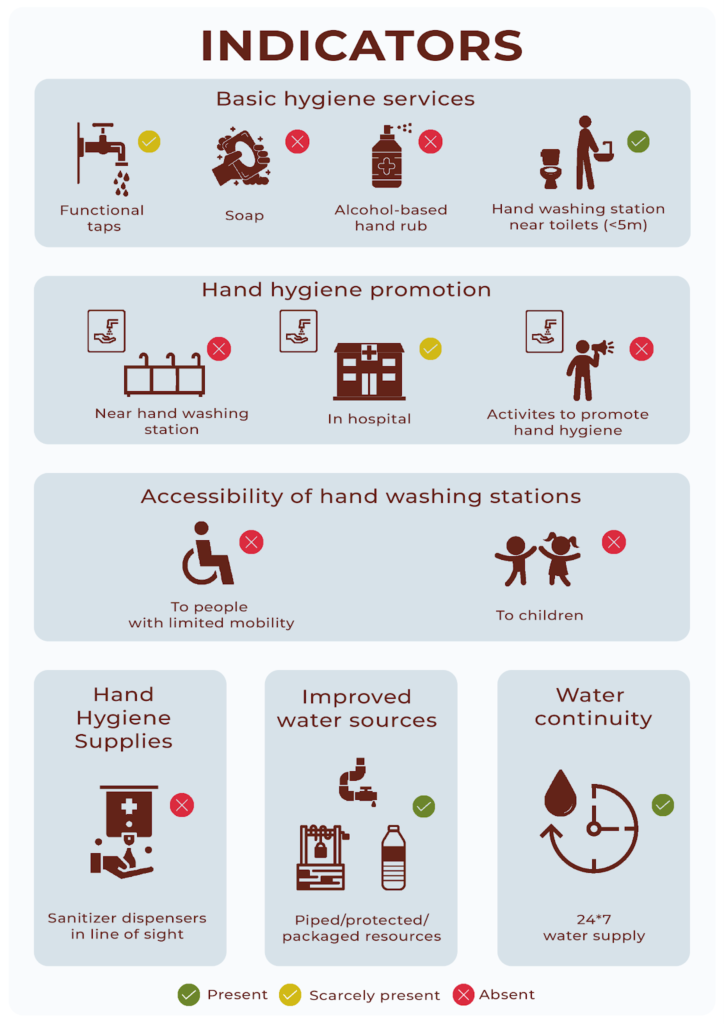

This article will discuss the case of Government General Hospital, Rajiv Gandhi Institute of Medical Sciences [RIMS] in Kadapa, Andhra Pradesh. The paper examines the hand hygiene indicators derived from WASH in Healthcare Facilities, Global Baseline Report 2019 (World Health Organisation and United Nations Children’s Fund 2019), in relation to each other, to view the processes and investigate the contemporary phenomenon of hand hygiene for the beneficiaries of the institution. To this end, the research is based on the observation of hand hygiene infrastructure at the hospital, supported by anecdotal evidence in the form of quotes from nurses and patients throughout this paper.

CASE STUDY

The government hospital’s vision statement reads that it aspires to ‘improve the quality of healthcare and make medical education accessible to all the eligible students of the region’. Recognised as a tertiary-level care hospital that provides highly specialised medical care, it has a total capacity of 750 beds with 1500-2000 patients frequenting the in-patient and out-patient blocks every day. The hospital offers complex procedures performed by specialists in cutting edge facilities. Since this hospital is situated in a chronically drought-affected district in Andhra Pradesh, where 19 of the past 23 years were drought years (YSR District n.d.), the importance of hand hygiene in this institution is especially significant. Further, a study suggests that hospitals in drought-prone areas have poor preparedness, response and recovery capacity (Wijesekera et al., 2020).

During the current COVID-19 pandemic, the hospital was one of the two dedicated government institutions providing medical assistance to the infected persons in the district headquarters. The facility becomes the default health centre for many district residents who cannot afford private hospitals. Therefore, it becomes more important that this state institution is equipped to provide safe infrastructure alongside medical assistance to the poorer sections of society. The maintenance of hand hygiene and an infrastructure that supports it plays a significant role as chances of contracting the virus are higher when compared to a non-covid hospital.

As discovered during this research, the Government general hospital, RIMS demonstrates an abysmal state of the hand hygiene infrastructure in terms of functional taps, availability of soap and sanitisers, and accessibility for children and disabled persons.

Figure 1: Below are the findings from the exploration of the hand hygiene indicators in this hospital

AVAILIBILTY OF SOAP AND SANITISERS

The ward toilets do not have any soap, even for patients admitted. However, the patients are aware of the importance of hand hygiene, despite the hospital not undertaking any actions to promote hand hygiene.

After the coronavirus outbreak, there seems to be a consensus among patients and visitors regarding the importance of hand hygiene. Therefore, even if the hospital does not provide for these facilities, some who visit the hospital carry their own soap or sanitiser. In conversation with a son taking care of his ailing father said, “We come from a village that’s very far away from this place. We bring our own soaps, sanitisers, and drinking water. There is hardly anything here. Even if there is anything, we don’t know how much we can depend on the hospital for our safety.”

Subbaraju Aavula, a patient, went on to say, “Ever since Covid, we have all been very scared of going near a hospital. Such is life that the place which saves life is also a place of horror now. Everybody is telling us that we should wash our hands regularly to be safe from this virus. But, how should we wash our hands if there are no facilities?”

A visitor complained, “This is the biggest hospital around this region. All of our district comes here. But there are no taps to clean ourselves. How can we be safe from each other if there are no taps? All celebrities come on TV to tell us to wash our hands, but what do we do with awareness if there are no facilities?”

Patients can also use the sanitisers present in the ward. However, an acute shortage of sanitisers in the hospital meant that patients rarely depended on hospital sanitisers. Nurses in the ward also corroborated this view. During a conversation with Kalavathi[1], a nurse, we noticed a doctor passing by with a sanitiser. On inquiry if the doctors had always carried their own hygiene supplies, Kalavathi stated, “No, it’s only in the pandemic that doctors are bringing their own sanitisers. Even we do the same. All the staff around do this because we don’t have enough supplies provided by the hospital.”

However, the healthcare staff disagree with the patients’ view that the lack of hand hygiene infrastructure is an institutional failure. The head nurse, Srivalli, tells me, “The patients who come here are illiterate. They have no awareness. They don’t know how to keep their surroundings clean. If we keep one soap near a handwashing station, it will be gone by the evening. They spoil the toilets. If it’s a public space, they just don’t care about keeping it clean.”

ISSUES OF ACCESSIBILITY

Rights of Persons with Disabilities Act, 2016, stipulates barrier-free access for the disabled in all parts of government and private hospitals and other healthcare institutions and centres. But the reality at the general hospital in Kadapa is different.

“Disabled toilets are locked because there is no use keeping them open. I have never seen disabled people using them. It is only normal people who use and dirty them. It’s just an extra burden for the sanitation workers to clean these toilets. So, we just converted them into staff toilets. And patients here don’t even care whether there are facilities or not!”, Malathi, a head nurse tells me. .

“Do disabled people’s toilets exist in this building?” questioned Mary, another nurse who has been working in the hospital for ten years.

“In our time, there was a lot of communication between patients and nurses. Whatever we learnt in our classroom, we used to tell patients in our rounds. But, nowadays, there is hardly any knowledge sharing happening!” Mary continued, “Without this, how can we make the present situation better?”

However, despite Malathi’s cynicism and Mary’s resignation about such a state of things, the staff has many suggestions to turn around the hospital in terms of infrastructure and stakeholder behaviour. In an interview with Rosy, a staff nurse, she enthusiastically ideated that, “Every patient bed should have a small sanitiser dispenser installed just like the saline stand, so when we go for rounds, we can ask the patients to use them. This would definitely increase the frequency of hand hygiene. And every ward entrance should have sanitiser dispensers stationed. We can even put wall mounted sanitiser dispensers where every hand washing station is. This way the soaps also wouldn’t go missing.”.

Another nurse Subbalakshmi added, “In the neighbouring district government hospital, they keep playing audio clips of safety measures to be followed during the times of COVID including when and how to wash your hands, exactly like a lift voice speaking in the background. I think that if people keep listening to something, they would start following it some or the other time. And these medical college students also can conduct some skits or awareness programs.”

When asked why these suggestions are not translating into actions, Subbalakshmi dejectedly replied, “Who would listen to us?”.

References

YSR District. (n.d.). “District Disaster Management Plan”. Accessed 14 January 2022, https://kadapa.ap.gov.in/district-disaster-management-plan-2/.

Wijesekera, Novil, Asanka Wedamulla, Sugandhika Perera, Arturo Pesigan, Roderico H Ofrin. (2020). “Assessment of drought resilience of hospitals in Sri Lanka: a cross-sectional survey”. WHO South-East Asia Journal of Public Health 9(1): 66-72.

World Health Organisation and United Nations Children’s Fund. (2019). WASH in health care facilities: Global Baseline Report 2019. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO and UNICEF. Accessed 14 January 2022, https://washdata.org/sites/default/files/documents/reports/2019-04/JMP-2019-wash-in-hcf.pdf.

[1] All interviewee names of nurses are changed.