In June 2014, I conducted a three-day workshop alongside The Fearless Collective at an all-girls, government school in Shivajinagar, Bangalore. The Fearless Collective is a South Asian feminist art project that uses immersive storytelling techniques to engage with underrepresented communities to create spaces for reclaiming and occupying the otherwise marginalised voices and narratives.

It was a new year, and the school had just reopened after the summer break. As I walked in, I noticed the girls of Class 9-A sitting tall in their seats, with straightened backs, lifted chins, gleaming with pride for stepping into a new academic year. Their school entrance was on a narrow and busy street, close to the city’s commercial heart. The main wall along the entrance had been turned into a spot for garbage dumping and was being used by passing men as a place to openly urinate, exposing the girls to a constant stench all day long. As a consequence, the Principal raised funds to have a local municipal body — Bruhat Bengaluru Mahanagara Palike (BBMP) — clear away the mess. The Principal also got in touch with us to work with the girls to transform the space into something the girls could take pride in.

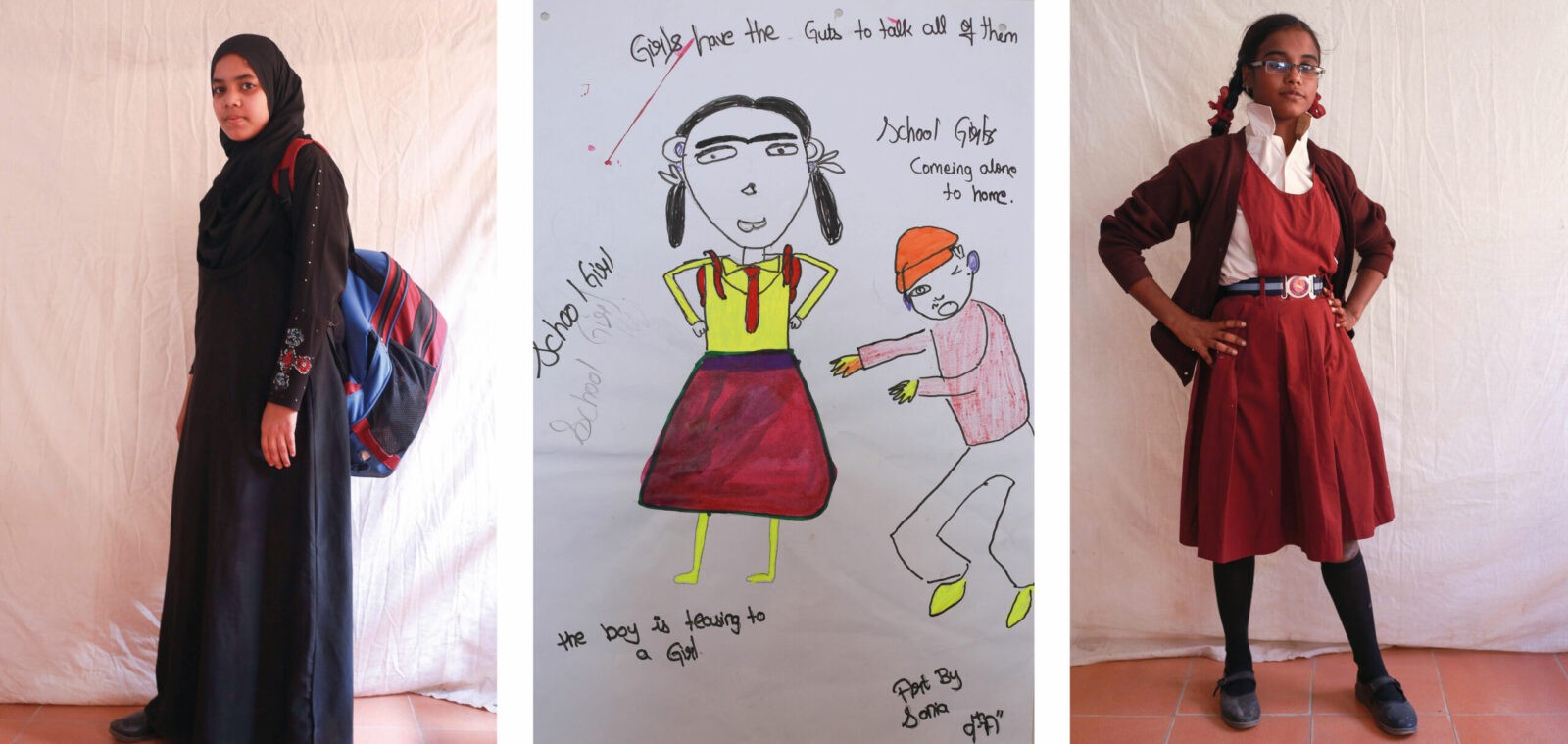

As we started off our conversation about what kind of mural they would like to have painted on the front wall, one of the girls asked: “I wonder if men would think twice about urinating on the wall if this were a boy’s school?”

This launched us into a discussion about how growing up as a girl often comes with strings attached. Together we discussed the things we could do to loosen these strings and hope to have them cut away entirely.

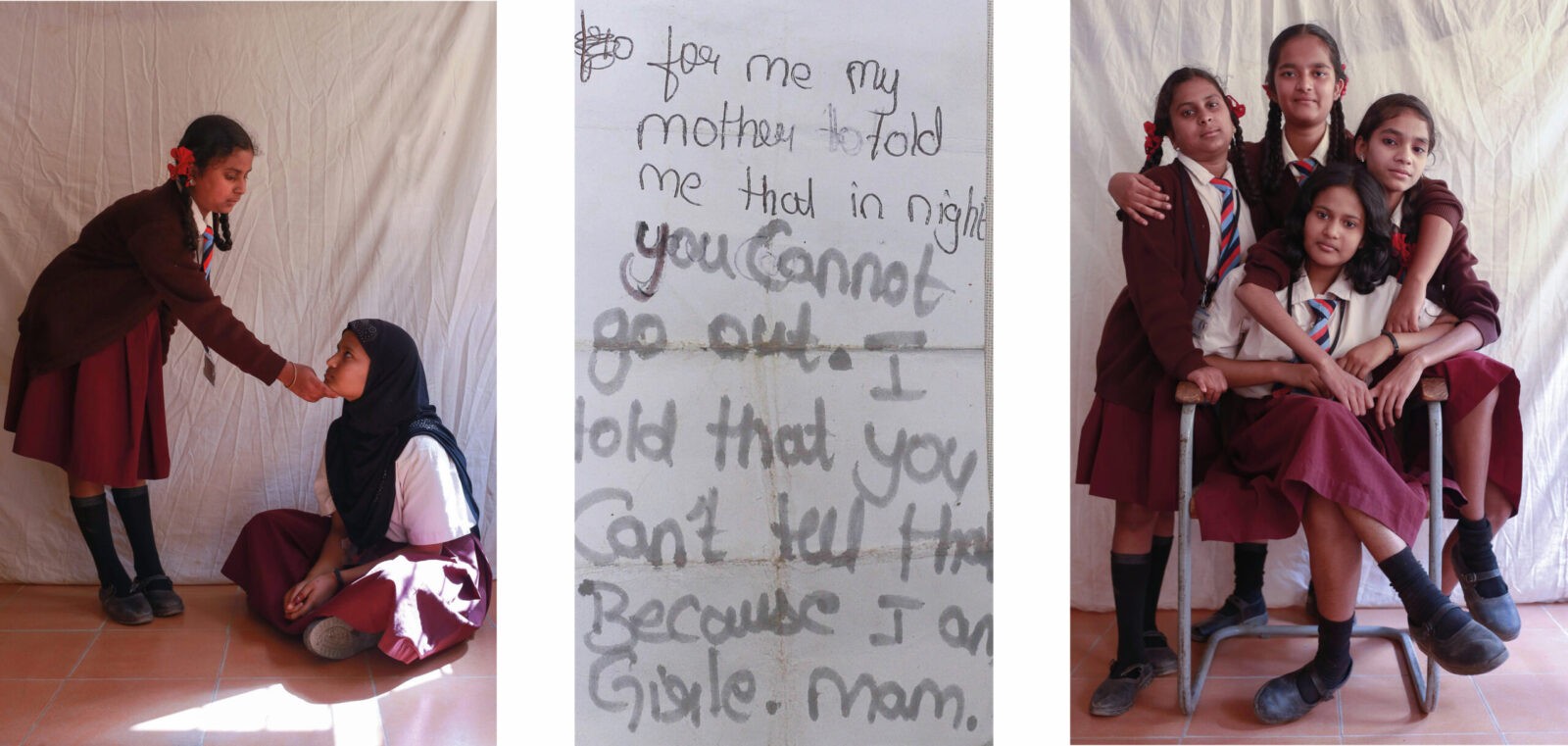

We spoke of ambition and how it was harder for girls to imagine a life for themselves. Since coming to school was already proving to be a challenge, several girls told us that they were not sure how much longer their parents would let them stay in school to continue their education or be allowed to attend college. One of the students, Roshni, mentioned how the end of every academic year meant a new round of negotiations with her father to allow her to stay in school. She was elated by the fact that this time she convinced her father to let her write her 10th Board Examinations. However, in return, she had to take on more household chores, which meant that she would devote less time for her school homework. Nevertheless, determined to power through, she decided to wake up early in the morning to finish her school work.

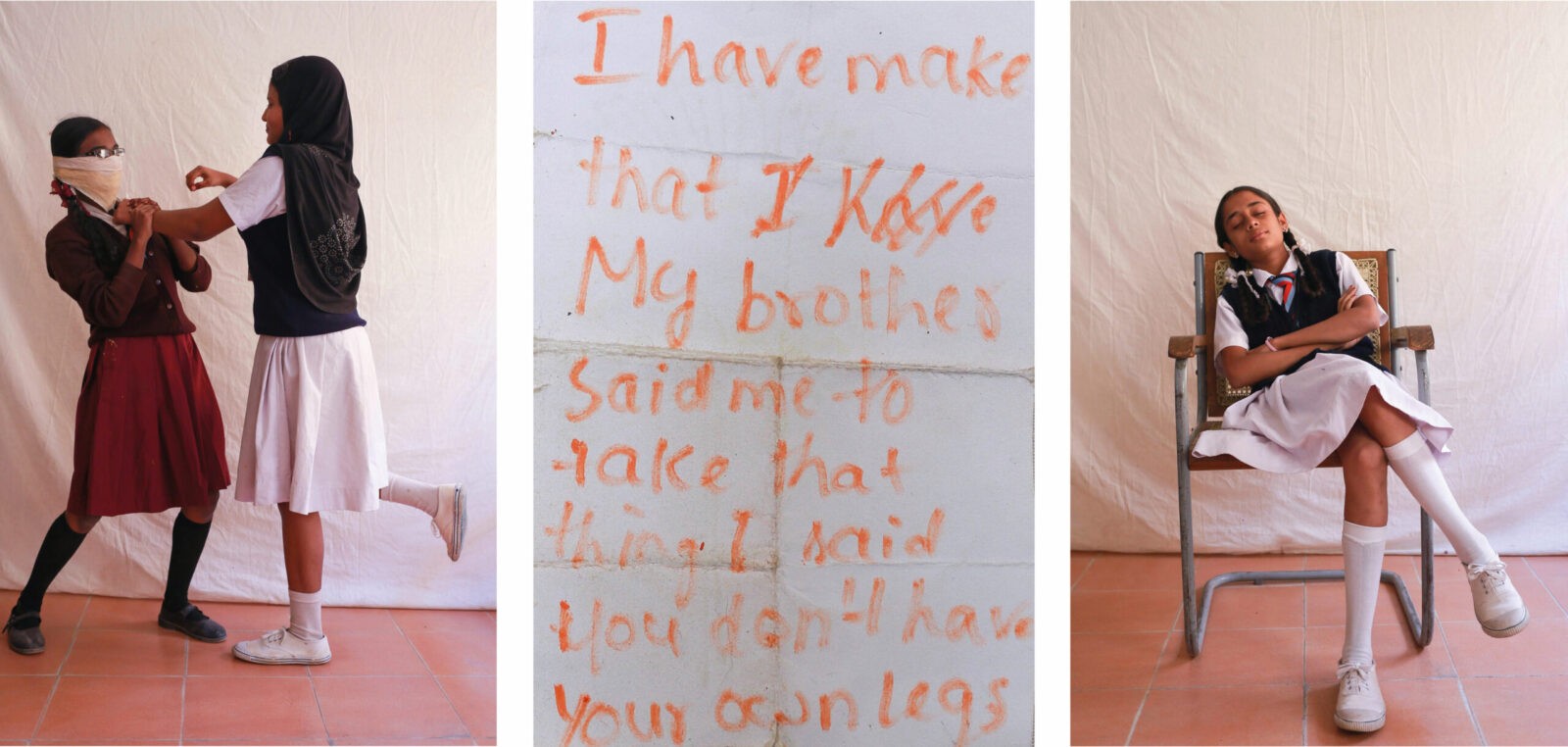

At this point, another student, Nasreen, added that she too was expected to help her mum in the kitchen irrespective of any schoolwork. In contrast, her brothers were allowed to go out and play for as long as they desired. Nasreen remarked in defiance, “I want girls and boys to be equal!”

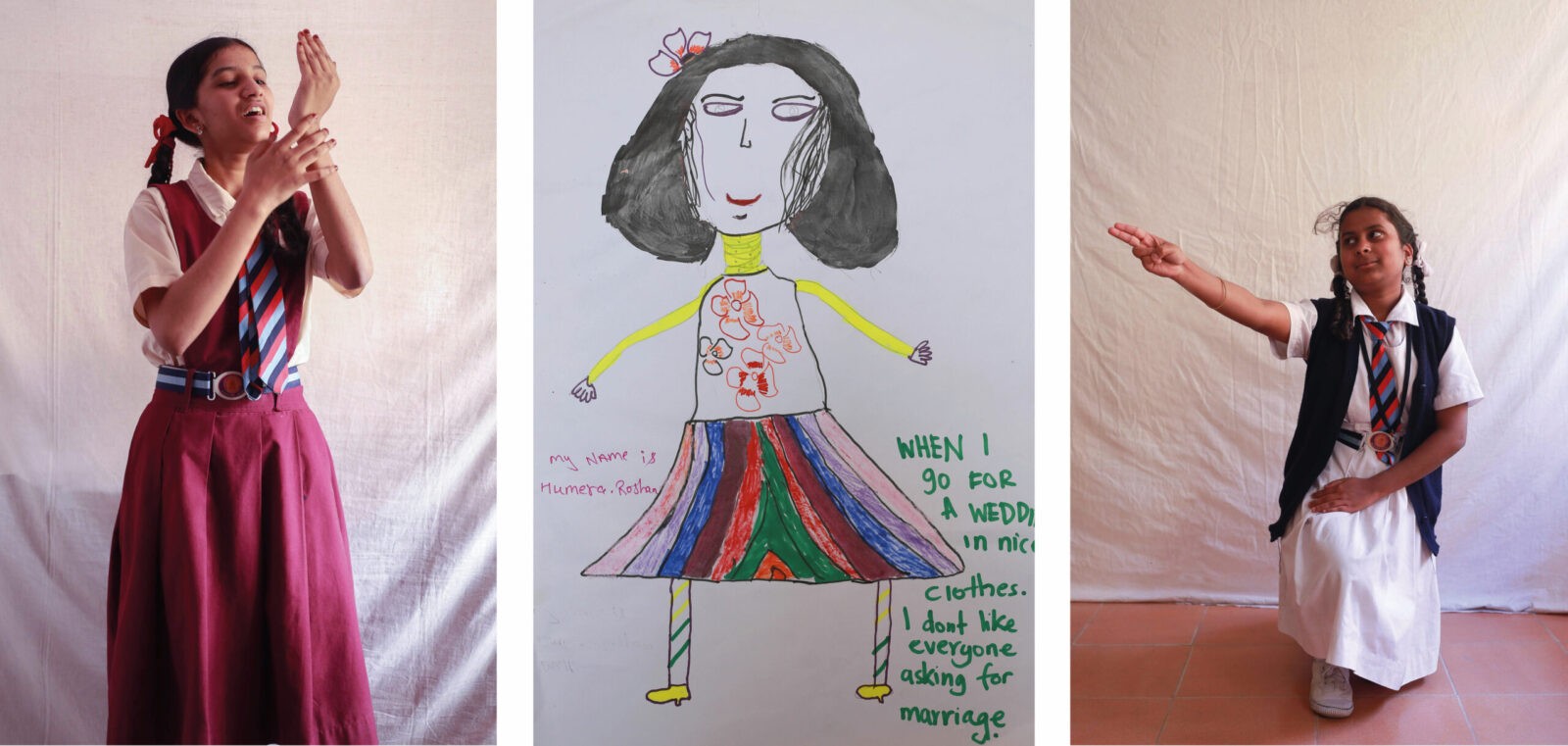

For our first exercise, we asked each of the girls to list out what they liked about being a girl and what they didn’t like. In response to the first question — what they liked about being a girl — many spoke about sharing a close relationship with their mothers, dressing up, wearing makeup, and cooking. While answering what they didn’t like, there was the resounding similarity… and this is when ‘rok – tok’ came up. (A common phrase in Hindi, rok means to stop, curb, restrict and tok means to scold or reprimand.) The girls complained that they were constantly being told what they could and (mostly) couldn’t do.

We set up a little photo studio where they could imagine and embody the person they wanted to grow into, a world where there was no rok – tok. These portraits were made as a result of my collaboration with the girls. During these sessions, they overcame little barriers in front of the camera by letting their hair down, sitting with their legs crossed (like a lady), and oozing with attitude. Normally, these were things they were told not to do, but here they were relishing the opportunity.

We shared secrets about sneaking out of the house and trying supari (areca nut). Talked about skinny jeans and being harassed on the bus. Our little studio became a safe space, where the girls posed as the person they wanted to become – a policewoman, a philanthropist, a mother.

Welcome to Class 9A