My grandparents fled Lahore in 1947 during the violent partition of the Indian sub-continent into India and Pakistan. I grew up hearing stories about everything they had left behind, how difficult it was for them to rebuild their lives in New Delhi, and how they believe that a part of them still lives and breathes in Lahore. Refugees, on account of being displaced, deal with the question of identity and belonging quite differently compared to the general population. They exist both inside and outside the definitions of nationality and community.

Travelling routinely to a friend’s house near Madanpur Khadar, I used to pass through one of the many Rohingya refugee campsites situated in South Delhi. Young Rohingya men standing and chatting near street-side tea stalls embodied, to me, the state of material and immaterial loss associated with leaving behind ancestral heritage and lived spaces, much like my grandparents.

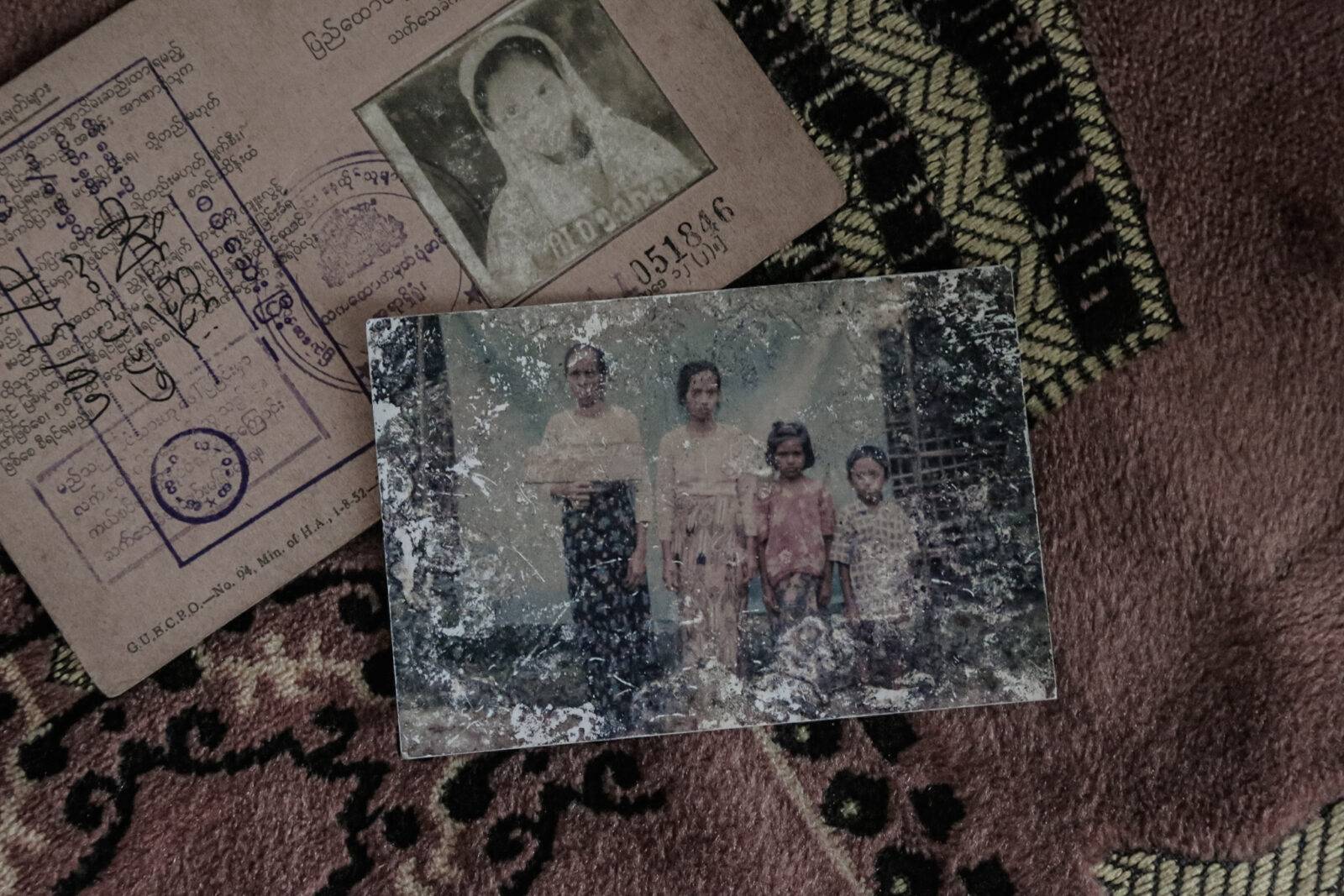

The Rohingya have been described as ‘the most persecuted minority in the world’ by the United Nations [1]. In 1982, with the passing of a new citizenship law by the government of Myanmar, a predominately Buddhist country, the citizenship of the Rohingya community, a Muslim-minority group, was delegitimised on ethnic and religious grounds [2]. Thousands of Rohingya populations, for years, have been fleeing to neighbouring countries like Bangladesh, India, Malaysia and Thailand to escape persecution, often unsuccessfully.

Most of the Rohingya communities residing in India came here after the wave of violence in Myanmar’s Rakhine in 2012 and settled in parts of Jammu, Telangana, Haryana, Delhi, and Rajasthan. In an affidavit submitted in the Supreme Court in 2017, the Indian government claimed that there were over 40000 Rohingya people living in refugee camps across the country [3]. On the other hand, there were 18000 Rohingya refugees registered with UNHCR in India, with an unspecified number being unregistered [4]. There are around 900 Rohingya refugees in camps in and around Shaheen Bagh, Madanpur Khadar, Okhla and Vikaspuri.

Most of the men in the Madanpur Khadar and Shaheen Bagh refugee camps work as daily wage labourers in nearby construction sites, factories and eateries. Rag picking is another common occupation. Many complain of wages being denied by contractors and factory owners. “They hire us but they pay half of the promised wages or don’t pay at all; they take advantage of us for not having any other choice”, says Mohammad Faruq.

Dil Mohammad, one of the community leaders in the Shaheen Bagh refugee camp talks about fear and nostalgia, both his own and that of the community. He says, “the recent verification process has brought back memories of the process which was conducted by the Myanmar government just before driving us out of our homes” [5]. Mohammad Usman, another community leader adds, “people are scared and we think after this verification, we will be sent back, and the relatives of some of the families who are still living in Rakhine whose names have been noted down in the verification forms will be in danger”. The people in the camp are visibly restless, thinking about their future. Their morning routine, apart from the usual activities, involves listening to the latest news about the condition of other Rohingya refugees in neighbouring countries.

One night, while going back home from the camp, I saw some children sitting in front of computers. They were being taught by a young man. On probing further, he told me that he is also from the camp and provides tuitions to the children living in nearby areas. Though he is a B.Com graduate wanting to pursue further studies, he can’t get into a college or a decent job as he doesn’t have any identity proof. His only options, he says, are open learning or a minimum wage job.

Yet, there is another side to the plight of the Rohingya. A strong sense of freedom resonates throughout the community. They acknowledge and enjoy the every day even amidst fears of eviction and deportation.