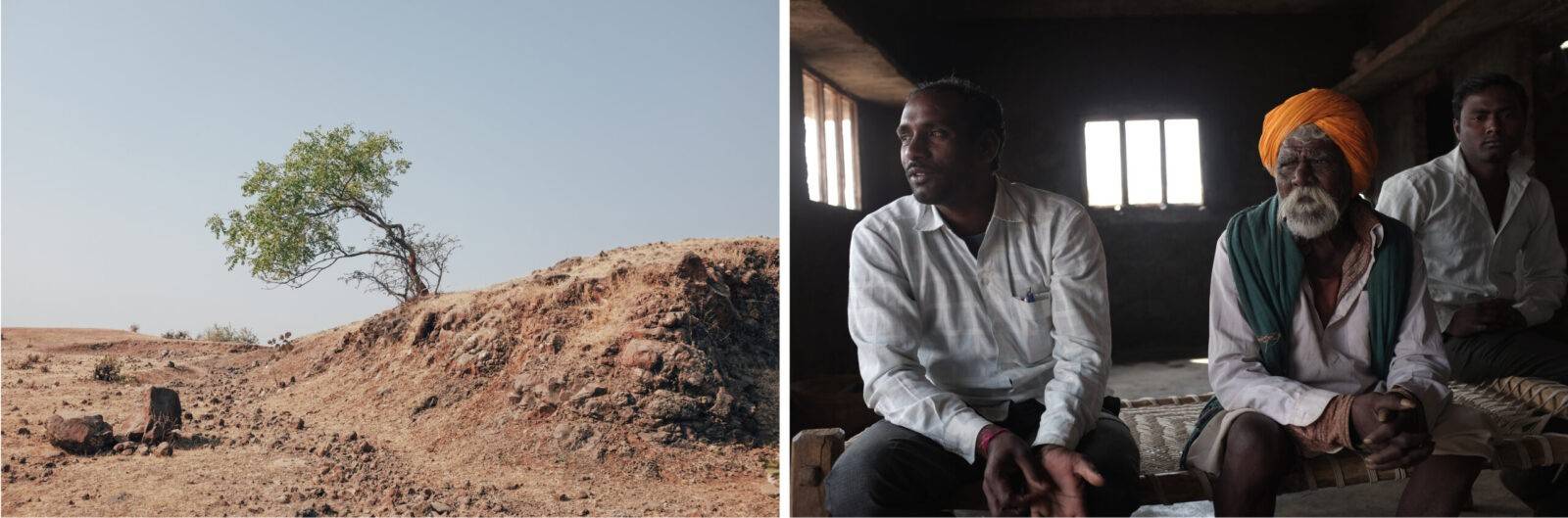

On my first visit to Bhikangaon in December 2019, I witnessed the skeletal remains of the failed crops bristling in harsh winds blowing across the barren dystopian landscape. Bhikangaon lies in Khargone district, in the southwestern region of Madhya Pradesh. According to the locals, around five decades ago, massive deforestation turned what was once a lush forest into a mountainous desert. The region consists of steep, undulating land with 90% of the total farmland covered with murram. A layer of hard Basalt rock lies under the soil, about 7-8 km deep, resulting in little soil depth and low soil fertility.

Due to the lack of forest cover, there is severe soil erosion and high rate of run-off. The soil in Bhikangaon also suffers from low moisture and nutrient content, severely impacting farming-based communities. The primary source of livelihood is rain-fed agriculture with extremely few pockets having access to irrigation. Lack of groundwater recharge and availability is a recurring issue. The thick layer of Basaltic rock under the ground contributes to very little percolation of water, leading to groundwater being next to zero. Digging wells and tube-wells through the hard rock is a big physical challenge and usually results in very little to no water being discovered

As a consequence, with agriculture not being a reliable means of livelihood in Bhikangaon, many families often migrate to distant towns and cities to work as wage labourers in fields, construction sites, among others. People travelling to cities often engage in back-breaking labour to earn minimum wage. The empty, abandoned homes of people bear testimony of this ongoing transition.

In Bhikangaon, many government and non-government organizations have come forward to start funding projects aimed at constructing sustainable watershed structures such as the watershed development project run by the central government – IWMP(Integrated Watershed Management Program [1]). Yet, several activities, such as construction of an earthen dam as a part of these projects have been gripped by a wide range of issues. For instance, on the one hand, while the locals state that the dam should be bigger in order to increase its water-holding capacity, the Forest Department on the other hand has issued an order against it as the submergence area of the dam would also cover some of the forest lands. Moreover, the employment opportunities generated by the construction of these structures have the potential to help some families stay back in their villages and earn their livelihoods. But with inadequate interventions in Bhikangaon in terms of making structures or buildings that require local labour, working as labour on construction sites is a rarity.

Even though efforts are being made to change the policies and to increase the labour rate, against the harsh backdrop of poverty, the hardships that this region has to endure are multifold, permeating to almost every facet of life and work. Ranging from water scarcity to topographical challenges, to lack of education and health facilities, necessary migration for work, Bhikangaon faces all these problems, and more.