Introduction

The social and economic emancipation of women cannot be discussed without one of the critical elements which continues to enable this change—mobility. This paper explores the concept of spatial mobility as experienced by women in urban and rural spaces, and draws connections with institutional measures undertaken through gender-based reservations in public transportation in the country to improve the same. In order to access employment, healthcare, education and other resources, it is imperative for women to have freedom of movement and to be able to access public spaces freely and safely outside of their homes. While we can assume that the need for mobility is quite universal irrespective of gender, with the constitutional safeguards which accompany it vis-a-vis Article 19(1)(d) guaranteeing the freedom of movement and travel within the country without any restrictions, the picture looks a little different for women.

Who Can Travel Among Women?

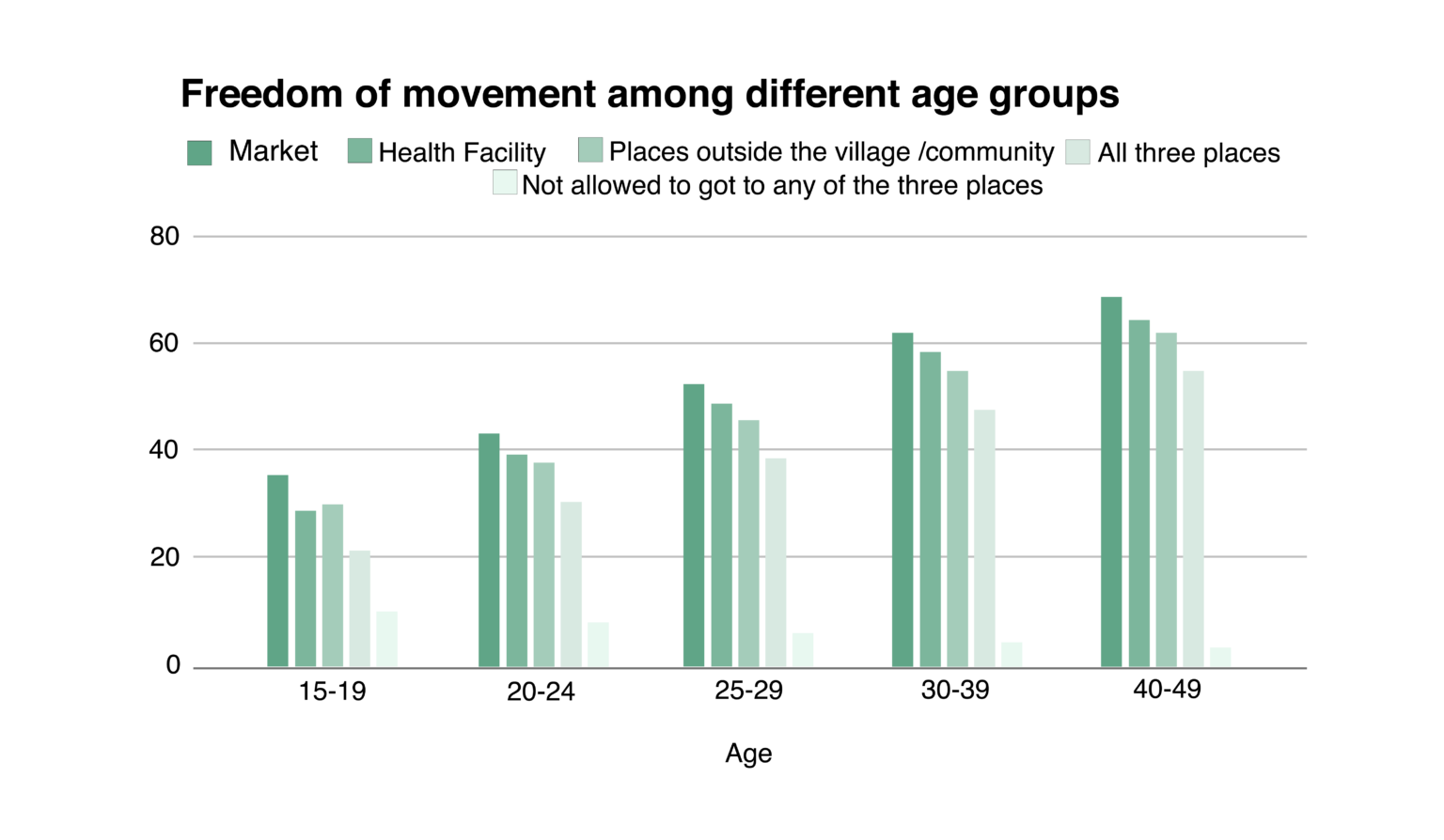

There are a number of national and regional data sets which attest to the lower mobility of women in comparison to that of men in the country. A lot of studies (Dyson & Moore, 1983; Farooq & Kayani, 2014; Gupta & Yesudian, 2006; Mason, 1997) in the past have demonstrated that there is a strong relationship between the freedom of mobility experienced by individuals and their household structures. Mehta and Sai (2021) tried to explore this concept further by studying the women’s relationship to the household head and whether that played a role in determining her autonomy of movement. On the basis of survey data from 9723 households across Dhanbad, Patna, and Varanasi, it was found that daughters-in-law have the lowest mobility among female respondents, while spouses have the highest mobility. The Census (2011) reported that women formed only 20% of all workers who reported travelling to work outside of their homes. Expanding the objective of a trip outside one’s home in peri-urban India, Sanchez et. al (2017) found that women were 3 times less likely to travel when compared to men. A study was also done by Goel et. al (2022) which observed “immobility” trends, which refers to the percentage of individuals who reported to not have gone out of their houses on the day of the survey. In Delhi, immobility was reported for 58% of the women and 26% for the men, and the gender gap was even higher in areas like Rajkot and Jaipur (Mahadevia & Advani, 2016; Saigal et al., 2020). In an early study by Jeejaboy and Santhar (2001), it was found that women in North India have to depend on other members of the household for approval to leave the house, due to established hierarchies in a predominantly patriarchal set-up. The National Family Health Survey (2015-16) explored this phenomena in greater detail. The women respondents aged 15-49 years were asked to pick all the locations that they were ‘allowed’ to go alone to. The women were asked to choose from the options of: (a) market; (b) health facility; (c) places outside the village/community. The results indicated that 54% of this group received permission to make a market trip, while 50% were allowed to visit the health facility and 48% to places outside the village or community. Viewed in totality, only for 41% of the cases was it permissible for the surveyed women to visit all three locations independently, while 6% were not allowed to go to any of the 3 places at all. Age is observed to be a significant variable which impacts freedom of movement among women, with only 22% from the ages 15-19 years allowed to visit all 3 places while 55% of ages 40-49 years allowed the same.

Figure 1. Source of data: NFHS (2015-16)

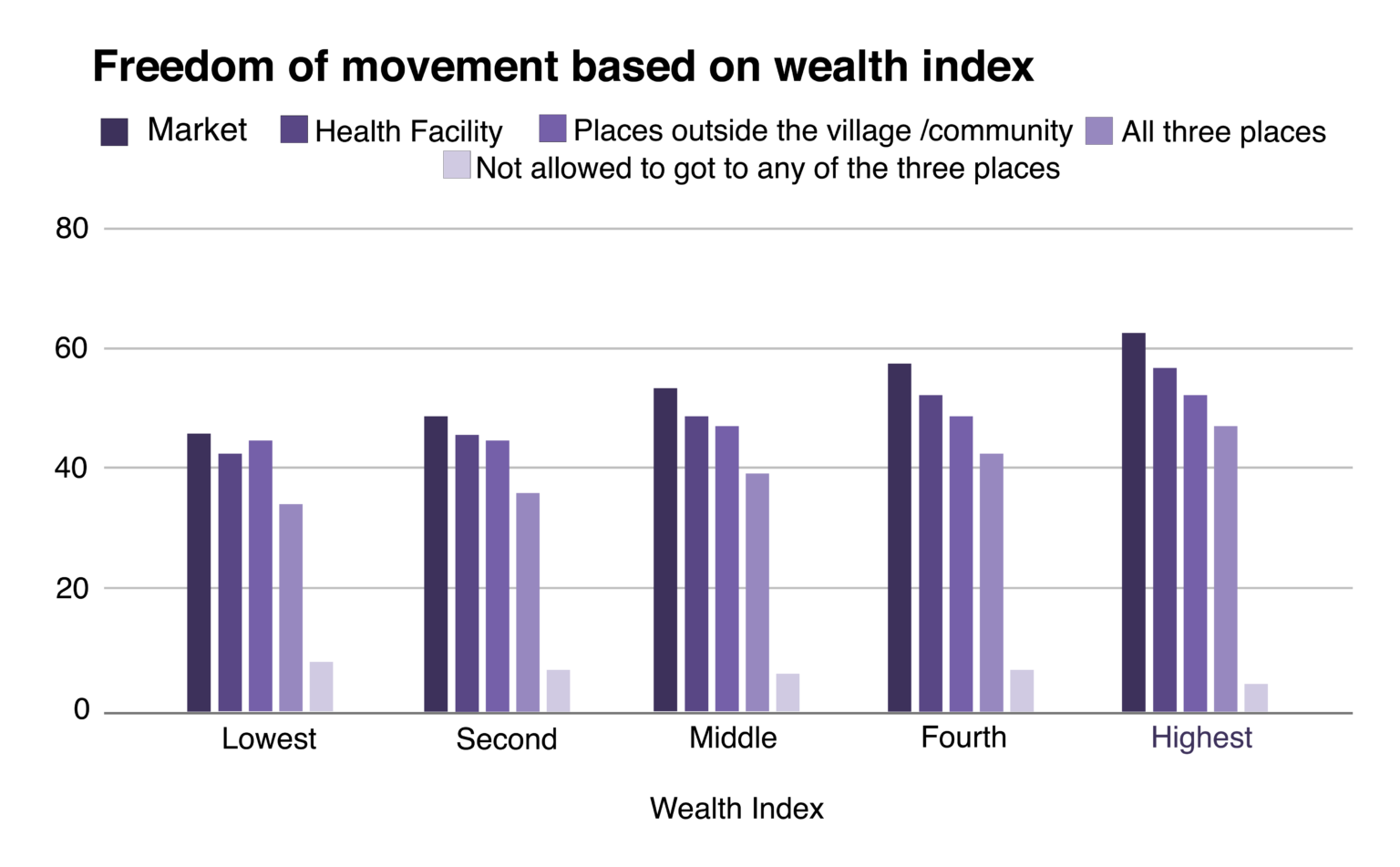

There is also some noted difference on the basis of geographical location, wherein 47% of women from urban households were allowed to travel alone to all 3 places, while 37% of women from rural households were allowed the same. This freedom of movement also increases with household wealth, wherein the percentage of women who are allowed to go alone to all 3 places increases from 35 per cent among women in the lowest wealth quintile to 47 per cent in the highest wealth quintile.

Figure 2. Source of data: NFHS (2015-16)

These data points help draw attention to the fact that there is not only a disparity in movement between men and women, but also specifically among women. The intersection of multiple social identity markers among women would probably lead to unique situations of restrictions or independence, as far as mobility is concerned. Through the studies highlighted in this section, the paper attempts to explore specific demographic factors that have been proved to influence which groups of women experience the freedom of movement, and where. The next section further elucidates the modes of transportation that are used by women who travel.

What Influences the Kinds of Transport Women Use?

Drawing inspiration from the aforementioned studies, it is evident that the current trends of women’s mobility outside of their homes is quite low, and needs to improve through a host of measures ranging from larger societal reform to improvement in infrastructure. The following sections specifically draw attention to the role of the ‘wheels’ behind one’s ability to freely move and travel in the country—public transportation; in the form of buses, trains, metros, autorickshaws, electric totos and so on. According to the National Highway Authority of India (NHAI), 65% of total passenger traffic is carried by road transport. Buses carry 90% of these passengers and form an essential constituent of road transportation. However, over the years, with rapid urbanisation and the country’s burgeoning population, the need for public transportation has far exceeded the current capacities of mobility systems in place. Additionally, with increasing sprawls, rapid motorisation, and retrospective urban transportation policymaking, the urban poor are especially at a disadvantage while navigating mobility in urban spaces (Abhishek, 2021). Subsidised travel rates by public buses are still too high for poor households to afford (Goel & Tiwari, 2016) and availability is severely limited as one moves to smaller cities. These data points have important implications when seen from a gender lens.

The percentage of women in India who walk to work (45%) is significantly higher than that of men (27%) who do the same, as a result of being limited by the lack of access to affordable means of transportation (World Bank, 2022). Public buses are one of the cheapest forms of transport in the country, but fail to service a majority of the population as the ratio stands at 1 bus per 10,000 people, according to Nitin Gadkari (Union Transport Minister). This translates to long waiting times between buses, large queues for each bus, and severe overcrowding when the bus does arrive. When viewed from a woman’s perspective, this proves to be extremely hasslesome and inconvenient. Women have an exhaustive range of domestic care work responsibilities at home including cooking, cleaning, and taking care of their children and the elderly and any trips made outside (if at all) for paid or unpaid work has to abide by a strictly tight schedule. A lot of times “trip chaining” is an integral part of the travel schedules of women wherein they hop on and hop off multiple modes of transport to reach a destination (World Economic Forum, 2024). The distance between the different modes of transport like metros and buses in the trip chain can result in more than half an kilometre walk, including up to 4 changes (Turner, 2012). A lot of times the public transport operators do not halt the vehicles properly at the stations, which results in a major safety hazard for women with children or luggage to board the vehicle (Malik et. al., 2020; Rahman, 2010). Therefore, the prospect of waiting for more than an hour just for hailing one or more forms of transport with a real probability of not getting a seat or space to stand ultimately either forces them to travel long distances by foot or severely limits their spaces of movement to areas close to their households. While the latter is considerable if it just entails visiting a marketplace or relatives, it becomes a serious problem whenever it results in missing out on economic opportunities, further tapering their workforce participation. Mehta and Sai (2021) corroborated the same by establishing a positive correlation between employment and mobility through their research with women respondents in north India.

Research conducted with women situated across metro cities also provided important insights. A study was done by Oxford Economics and Uber to study the mobility patterns of 7000 ride-hailing commuters across Mumbai, Delhi, Kolkata, Bengaluru and Chennai. 73% of the women in the respondent pool went to work and used cab-hailing apps as a major component of their travel, which is also indicative of the urban elite with access to a certain kind of income and resources; and not necessarily reflective of the entirety of the female labour force participation rate of 37% (Periodic Labour Force Survey, 2022-2023). A majority of these women respondents in the Oxford Economics study were noted to consider safety as a key priority in their decision-making around taking up jobs and viewed technology-enabled safety in ride-hailing apps as being important in that consideration. 75% of the women also mentioned that they use ride-hailing because they felt that it offers a much safer alternative to other forms of transportation. Lastly, 50% noted that the utility of the apps also stemmed from the fact that it allows the women to plan their schedules more efficiently without time drainage along the way in wait times. A third of the survey respondents mentioned that having this facility helped them access a wider number of work opportunities. Another significant study in this domain which tapped into the educated and working women demographic consisted of the Ease of Moving Index India Report (2018) by the Ola Mobility Institute. Data analysed from the responses of 9935 women across a range of Indian cities showed that 59% of the respondents used public transportation, which progressively declined with an increase in income. The reasons for using the same included affordability (40%), convenience (20%), time saved (18%), and 15% stating that they don’t have any other means of transportation to access. All of these studies help highlight trends of women’s mobility across different socio-economic characteristics and geographies, and also demonstrate the fact that there cannot be a one solution fits all as far as making public transportation accessible is concerned. The next section navigates through one of the most important considerations women have in their decision making around travel—safety.

How Safe is Public Transport in India?

A significant factor which collectively deters women across different demographic factors from travel is the lack of safety they experience while using public transportation systems in existence and studies conducted over the years in India have attested to the same. In Delhi, more than 90% of women surveyed had experienced some form of sexual harassment within the preceding year (Jagori, 2010). The study revealed that 51% of the participants encountered harassment while using public transportation, while another 42% experienced it while waiting for public transport. Comparable research conducted in Mumbai, Kerala, Guwahati, and Bengaluru also indicated elevated levels of sexual harassment and daily violence. In a study conducted by Sakhi in 2010 focusing on two cities in Kerala, it was found that in Kozhikode, 71% of women faced harassment while waiting for public transport, and 69% experienced it while using public transport. Similarly, in Trivandrum, over 80% of women reported experiencing sexual harassment while either waiting for or using public transport (Sakhi, 2011). In Mumbai, a survey carried out by Akshara in 2013 showed that 46% of women encountered sexual harassment on buses, while 17% experienced it on trains (Akshara Centre, 2015).

Moreover, a joint study by Safe Safar, Safetipin, and UCL conducted in Lucknow revealed that 88% of respondents had been subjected to sexual comments while using public transport (Safe Safar, Safetipin, & UCL, 2014). A survey conducted by the Bengaluru Metropolitan Transport Corporation (BMTC) in 2013 among female commuters indicated that two out of three commuters regularly experienced harassment (Deccan Herald, 2013). Furthermore, the 2014 Thomson Reuters Foundation survey on unsafe transport in capital cities worldwide ranked Delhi as the fourth most unsafe public transport system among the cities surveyed, following Bogota, Lima, and Mexico (Thomson Reuters Foundation, 2014). A global labour survey conducted by ILO (2017) found that it to be one of two major challenges experienced in women’s mobility and which contribute to the commuter gap between men and women. 56% of women were reported to have been sexually harassed while using public transportation, according to a 2021 study by the Observer Research Foundation. The same study also found that 50% of its respondents did not take up a work or educational opportunity as a result of being apprehensive about the safety of the commute needed in the process. 63% also reported that their safety concerns with public transportation stemmed from its poor infrastructure and history of involvement in accidents. 86% of the sample also reported that they would switch from other forms of transport to public transportation more often if they felt that the latter was safer, cleaner and had better connectivity. The frequent safety issues women face on public transport mean that female passenger journeys are skewed towards the daytime and shorter distances. The next section provides insights into institutional measures taken over the years to boost women’s usage of public transit in the country and improve their experiences of the same.

Overview of Policy Measures for Women’s Transit in India

One of the earliest regulatory frameworks which were introduced to cater to women’s needs during public transit consisted of the Railways Act, 1989. Section 58 of the same stipulated the allocation of accommodations for female passengers by Indian Railways. This included six berths reserved in sleeper class on long-distance Mail/Express trains, along with quotas of lower berths in Sleeper and AC classes for senior citizens, women over 45 years of age, and pregnant women. Additionally, second-class accommodation was provided in SLR coaches on most long-distance trains. To cater to the needs of unreserved passengers, designated coaches/compartments were mandated for allocation for women in EMU/DMU/MMTS trains, based on demand and availability. Ladies special services were also brought in to operate on suburban sections of major cities such as Mumbai, Kolkata, Secunderabad, and Chennai, as well as on the Delhi-NCR sections. Lastly, separate toilet facilities and waiting rooms for women were to be made available at important stations. With respect to reforms made in 2021, the Railway Protection Force (RPF) launched the ‘Meri Saheli’ initiative nationwide on October 17, 2020, to enhance safety for female train passengers. The focus was on safeguarding women, especially those travelling alone, throughout their journey. Lady RPF personnel were tasked with escorting Ladies Special trains, with instructions to maintain vigilance over solo female passengers, ladies coaches during transit, and at stopping points. Drives were to be initiated to prevent unauthorised male entry into female-designated compartments, ensuring the safety and security of women passengers across the railway network.

Major conversations started happening about revamping India’s urban mobility systems for women in the immediate aftermath of the Nirbhaya movement in 2012. A Nirbhaya fund was created by the Government over 2013-16 to fund a range of schemes aimed at improving women’s safety, especially while in transit. Under the same, the Cabinet Committee on Economic Affairs commissioned a unified system at the central and state level, including the City Command and Control Centre for GPS tracking via emergency buttons and video recording in public transportation for 32 cities. Over time, different states have also implemented their own set of measures at different points of time for improving women’s safety on public transit systems and to generally boost women’s utilisation of these forms of transport.

In 2016, women-only buses called ‘Tejaswini buses’ were introduced by the Maharashtra Government which would travel short distances during peak hours with women drivers and women conductors (Gaikwadi 2017). In 2018, the state administration in Patna brought out a 65% reservation in all city buses running in the capital city, in response to a massive demand by women passengers. With a major spike in the number of women travelling during peak day time hours as well as in the evening, this reform was undertaken to ensure that women get adequate seats during their journey and male commuters are free to occupy these reserved seats, in case they run empty during any route. Between 2018-19, the reservation of first coaches in metros for women was implemented in Delhi, Hyderabad and Bengaluru. In 2021, the Mumbai Metropolitan Region Development Authority (MMRDA) brought out a special coach reservation for women in the western suburb metro services. In 2023, the Karnataka government introduced a free bus travel scheme for women in the state who are domicile residents, students and linguistic minorities. Government-issued photo identification and address proof will suffice for the first 3 months of free travel for a female commuter, after which a ‘Shakti Smart Card’ can be issued through an online portal called ‘Seva Sindh’. City, ordinary and express bus services were all included in this scheme. All in all, this section makes it clear that different states in the country have adopted varied and unique approaches to solve the issue of women’s absence in public transport as well as many inconveniences involved in their travel. Some schemes have done well, whereas others have faltered and give rise to questions of gaps in administration and outreach efforts.

More Women in Buses, Less on Foot: Recommendations for a Mobile Future

For any reforms to be planned effectively and at scale, the generation of evidence on the ground situation is imperative. A national comprehensive baseline assessment needs to be undertaken across different public transport systems and their pick-up points from a mixed group of Tier I, Tier II, and Tier III cities to assess mobility patterns on the basis of gender. This can include surveying a socio-economically diverse sample of women travellers waiting at bus and auto rickshaw stops, metro and local railways stations for their upcoming journeys. The respondents can be asked a wide range of questions including their aim of travel, travel schedule, how travel timings are planned, length of trip and modes of travel, preference of routes, travel budget and more, as well as the rationale behind each choice made. Additionally, these surveys can also serve as a metric to determine the effectiveness of women’s reservations in public transport brought about by different state governments. By understanding what modes of public transport different women choose to take on a daily basis and why, one can draw connections with whether the reservation benefits positively influence women’s decision-making around travel and assess gaps and methods to improve their inclusivity. Another component that can be added to strengthen this data can be the inclusion of additional questions on women’s travel choices/preferences in the existing ‘women empowerment’ section of the National Family Health Survey of India. Through this measure, data will be captured for women located at any point in a spectrum of mobility, ranging from women who are not able to or have not travelled at all to women who undertake extensive and frequent travel. The role of social norms can also be recorded in this process wherein the respondents can be asked to indicate whether each travel choice made is on the basis of permissions taken from the household, independent decision making or a mix of both. Further probes can be designed to substantiate the same.

Most of the measures that have been brought in till date to help counter the high rates of sexual harassment and abuse faced by women during public transit usually places the onus of taking action on the women themselves. They are expected to approach the police, lodge a complaint and follow through with the entire lengthy process. Moreover, the prospect of having to make an additional trip to the police station in the immediate aftermath of such an event would probably also further contribute to the underreporting of such incidents, especially considering the intersection of stigma with the time poverty experienced by several women. A 2012 Supreme Court judgement mandated that on the raising of a complaint of sexual harassment in the middle of a moving public vehicle, the driver is supposed to drive the victim to the nearest police station, failing which, the former’s driving permit stands to be cancelled. However, there is hardly any data which corroborates the existence of this practice over the years and at present. Hence, it is crucial for the ease of accessibility and immediate response timings should be integrated into complaint-raising systems, especially through the administration of a special helpline for women to report such incidents, or raise concerns in situations where they feel unsafe during transit and subsequently can be assisted by a team on standby. This helpline number should be heavily advertised across all metro, bus and train routes with dedicated response teams on standby across different public transit routes.

Secondly, while having strong redressal mechanisms, surveillance at underserviced transit spots and building anti-violence laws are important and have been advocated for over the years, systems have to also be brought in which prevent such incidents from happening in the first place. To make public infrastructure safer and more gender-sensitive, women’s safety audits should be widely implemented across urban and peri-urban areas in the country. With the aim of improving urban design, making public spaces more gender-friendly and free from violence, the ‘Women’s Safety Audit Tool’ was first introduced as a participatory instrument to help women work directly with municipal authorities, community institutions and other civil society groups. In this, public spaces and workplaces are critically evaluated by all stakeholders from the lens of safety and ease of usage for women, and necessary changes needed to be made are implemented. Canada was the first country where such a tool was developed following the 1989 report by UN-HABITAT on violence against women (UN-HABITAT, 2009). Delhi has been one city in India wherein such women’s safety audits have been conducted periodically by an organisation called ‘Safetipin’, which actually resulted in the decline of dark spots in the city from 7500 to 2700 (World Bank, 2022). This approach could be utilised to develop a special focus on safety gaps for women in transportation infrastructure, including the condition of seating and lighting in buses and bus stops, infrastructure of women’s toilets in metro and railway stations, and the safety of women’s reserved coaches in both.

A country’s public transportation system needs to be safe, clean, affordable, and accessible. The only measure that can reduce massive overcrowding on buses and trains is an expansion of their fleet. Figures mentioned in the earlier sections have demonstrated that there is an urgent need for funding an exponential increase in public transportation infrastructure to reduce the demand-supply gap, while strengthening the quality of the existing transit systems in place. First and last mile connectivity needs to be improved, through the institution of public-funded, subsidised feeder transportation systems (electric totos, vans, etc.) in peri-urban and remote areas, especially keeping in mind the trip-chaining patterns of women. This would help significantly boost interconnectivity between stops and drop-points and reduce distances travelled on foot by women. Additionally, different initiatives undertaken by union and state governments from time to time do reflect a clear policy inclination towards improving women’s mobility in the country, but lack a unified, targeted approach. For example, the NFHS (2015-16) data clearly indicated that women from the poorest urban households tend to experience the lowest levels of freedom of movement, while other surveys have shown that women with higher incomes from well-developed urban spaces have the highest levels of mobility and prefer to access and utilise ride-hailing apps or personal vehicles (Oxford Economics, 2023; Ola Mobility Institute, 2018).

Poor women engaging in low-skill employment only have the options of walking, irregular modes of public transport or just not getting out of their houses at all. This means that more needs to be done to ensure that free or affordable public transit schemes for women do end up reaching the most vulnerable who have the least amount of access to travel or even travel information. Therefore, it is pertinent for governments to undertake extensive advocacy outreach efforts about existing schemes on free or subsidised travel for women. Since decision-making around travel (independent or otherwise) is quite likely to impact a woman’s prospective or current employment, innovative approaches can be undertaken to loop both these sectors together. For example, pilot interventions can be introduced in a cluster of districts, wherein existing employment and skill development schemes being run can have pre-arranged buses for the women workers to travel safely to the site of work and back home free of cost as a part of the arrangement. The results of this intervention can be compared with other district clusters where the same schemes are operational but not tied in with free bus travel for its women, to see whether the former results in more take-up of women’s participation in these schemes in comparison to the latter. Similar interventions can be designed for adoption in different states to help enable public transportation services to ultimately catalyse higher women’s labour force participation rates in the country. Lastly, strengthening transit systems and making them more affordable and inclusive would also help ensure that the women who do take up informal employment are at least not forced to live in precarious, makeshift settlements near their place of work, which often run the threat of evictions.