Introduction

Ever since independence, from the time of partition till the Kargil War in 1999, India has had to fight several wars. Safeguarding our borders from the ‘two-front threat’—that of Pakistan and China—compelled the erstwhile governments to equip the forces with the modern arms that matched in quality and quantity with the arms that America supplied to Pakistan. This has led to India’s effort towards self-reliance in defence production. However, despite efforts, India’s indigenous military R&D program struggled to develop modern weaponry, with only limited success in infantry arms production. Consequently, the country relied on licensed manufacturing from the Soviet Union (later Russia), but delays in production often rendered designs obsolete, making outright imports necessary and prolonging India’s path to defence self-sufficiency (Deshingkar, 1983). Every time self-reliance in or indigenisation of defence manufacturing is discussed, it is important to note two of its crucial aspects. One, strategic importance for national security, and the other, economic impact on industrial growth and job creation.

The ‘two-front threat’—a term coined for the notorious neighbours on the north and west of India, is still a reality. As recently as on March 8, India’s Army Chief said that “the two-front threat is a reality, and there is a high degree of collusivity” (Business Standard, 2025). Considering the turmoil in the neighbouring countries including Bangladesh, it is pertinent for India to ensure self-reliance in national security and strategic autonomy. Dependence on imports for arms and ammunition leads to potential technological deniability, delays, but most of all geopolitical pressures (Feldhaus et al., 2020). Hence, defence indigenisation is primarily a strategic necessity for India.

Even from an economic standpoint, too, self-reliance in defence manufacturing is essential. Traditionally, India was heavily dependent on foreign suppliers, importing nearly 65 to 70% of its defence equipment. This scenario has gradually evolved, with nearly 65% of defence equipment now being produced domestically (Business Standard, 2025). This shift highlights the expansion of India’s defence industrial base, which includes 16 Defence Public Sector Units (DPSUs), over 400 licensed companies, and around 16,000 Micro, Small, and Medium Enterprises (MSMEs). The private sector contributes approximately 21% to this growing domestic production (PIB, 2025).

Another important development due to indigenisation is the evolving map of industrial geography in India. What is noteworthy is the proactiveness of the state governments in shaping this landscape. States like Uttar Pradesh and Tamil Nadu are setting up Defence Industrial Corridors (Make in India, n.d.) which are providing space for manufacturing units, optimising logistics and facilitating collaboration between public and private enterprises. Even the regional hubs such as Bengaluru for Aerospace and Missile Development (Adnal, 2025), Hyderabad for Missile and Electronic Warfare Systems (The Economic Times, 2024), Pune for Armoured Vehicles and Artillery (IDRW, 2025), Chennai’s Kattupalli Shipyard, Goa’s Goa Shipyard Ltd, Kochi’s Cochin Shipyard Ltd, and Mumbai’s Mazgaon Dock Shipbuilders Ltd for Naval Shipbuilding foster specialisation in niche areas, improve the supply chain and develop a skilled workforce in those regions, thereby bolstering India’s competency in global defence sector.

This research examines India’s historical reliance on arms imports and its gradual transition toward defence indigenization through initiatives like Make in India. It explores the evolution of government policies that are fostering a self-sufficient defence manufacturing ecosystem, reducing dependence on foreign suppliers, and strengthening domestic capabilities in weapons, and ammunition production. By analysing key policy reforms and industry developments, this paper aims to highlight the progress, challenges, and future potential of India’s journey toward self-reliance in defence manufacturing.

Historical Evolution of Defence Manufacturing in India

During the British rule over India, the Britishers had established many ordnance factories in the country for production of guns and ammunition. In 1947, India inherited 18 of those ordnance factories and other Defence Public Sector Units. In view of the three wars fought by the Indian Army, 23 more ordnance factories were established by various governments after independence. From October 2021, a total of 41 ordnance factories operating under the Ordnance Factory Board were transferred to 7 Defence Public Sector Undertakings (DPSUs) by the Government of India (Directorate of Ordnance, n.d.). The Ordnance Factories are responsible for the manufacturing of (1) Arms and Ammunition; (2) Weapons, Vehicles and Equipment; (3) Materials and Components; (4) Armoured Vehicles; and (5) Ordnance Equipment.

However, considering India’s imports from the erstwhile Soviet Union and now Russia, it is clear that the indigenous manufacturing was highly inadequate for the country’s strategic needs. USA’s alignment with Pakistan, in addition to the then Defence Minister’s socialist inclination, prompted India’s move towards the USSR to tackle Pakistan (Lalwani et al., 2021). From the 1950s, India started to import weapons from Russia, including Ilyushin Il-14 cargo transport aircrafts, followed by MiG-21 fighter aircrafts (Bommakanti & Patil, 2022). During the 1962 war with China, India faced severe shortages in basic defence essentials, including winter gear for soldiers deployed in high-altitude battles. Similarly, in the 1965 and 1971 wars, India had to rely on outdated World War II-era fighter aircraft and battle tanks, while its adversaries possessed far more advanced and modern weaponry (Pathak, 2022). These circumstances led to India importing defence supplies from many countries, including France, USA, Israel, etc.

The 1991 economic liberalisation initiated India’s shift from a heavily regulated state-controlled economy towards a more market-oriented, liberalised economy. The policy focused on liberalisation, privatisation, and opening up India’s economy (Walia & Mishra, 2024). However, it was not until 2001, that the political leadership decided to liberalise defence production to bring in private entities (Behera, 2024). Additionally, the Bofors scandal, which exposed corruption at the highest levels of government, led to the electoral defeat of Prime Minister Rajiv Gandhi (Srivastava, 2015). It may have also led to a prolonged phase of policy paralysis – delaying critical procurements and much-needed defence reforms as policymakers grew increasingly cautious in the aftermath. Hence, the duration from 1990 to 1999 was often referred to as the Lost Decade in defence procurement (Unnithan, 2011).

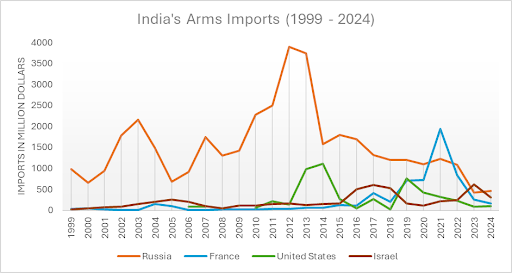

While analysing the defence imports, the imports from 1999 onwards alone are considered since the Ministry of Defence did not acquire any new defence equipment between 1990 and 1999 (The Lost Decade).

Source 1: SIPRI Arms Transfer Database

Source 1: SIPRI Arms Transfer Database

The chart illustrates India’s arms imports from four key suppliers—Russia, France, United States, and Israel. The data reveals notable trends in India’s defence procurement strategy, reflecting shifts in geopolitical alignments, security needs, and domestic policy changes. Over the years, India has transitioned from heavy dependence on a single supplier, primarily Russia, to a more diversified approach, seeking weapons and technology from multiple nations.

Russia has historically been India’s dominant arms supplier, with significant spikes in imports between 2002-2005 and 2010-2014, peaking around 2013-2014 at nearly $4 billion. These peaks coincide with major defence deals, including the procurement of fighter jets, submarines, and missile systems. However, after 2015, Russian imports began to decline steadily. This shift can be attributed to India’s efforts to reduce reliance on a single supplier and enhance indigenous defence capabilities through policies like ‘Make in India.’ The most recent data (2023-2024) shows that Russian imports have fallen significantly, bringing them closer to the levels of other suppliers, a stark contrast to their previous dominance.

The United States emerged as a significant supplier between 2010 and 2016, with a notable peak around 2014. This period saw India acquiring key defence equipment such as Apache and Chinook helicopters (Boeing, n.d.-b), C-17 transport aircraft (Boeing, 2019), and P-8I maritime patrol aircraft (Boeing, n.d.-a). However, post-2016, U.S. arms imports declined, likely due to India’s growing emphasis on domestic production and strategic shifts in defence procurement.

France’s role as a defence supplier remained relatively modest until a sharp increase between 2019 and 2021, coinciding with India’s procurement of Rafale fighter jets. This surge reflects India’s diversification strategy, where high-end technology and reliability are prioritized over bulk imports. While imports from France have decreased since the peak, they continue to remain higher than in previous decades, indicating a long-term strategic partnership in the defence sector.

Israel, on the other hand, has maintained a relatively stable presence in India’s defence imports. Unlike Russia or the United States, Israel’s exports to India have not seen extreme fluctuations. It has consistently supplied India with advanced weaponry, missile defence systems, and drones. This steady engagement highlights Israel’s niche role as a provider of cutting-edge military technology, which complements India’s evolving defence needs.

The trend in India’s arms imports reflects an effort to move toward self-reliance while maintaining strategic international partnerships. The declining overall imports, especially after 2020, aligns with India’s commitment to indigenous defence manufacturing. The success of India’s indigenisation efforts will ultimately determine the extent to which it can achieve true self-sufficiency in defence manufacturing while balancing strategic ties with global partners.

Early Indigenization Attempts

The history of the Light Combat Aircraft (LCA) Tejas, the Integrated Guided Missile Development Programme (IGMDP) and other such projects exemplified the mixed outcomes of India’s early indigenisation efforts. While they took significant steps toward self-reliance, they also revealed persistent dependence on foreign technologies and delays due to limited private sector involvement. These experiences highlighted the need for broader collaboration and reforms to build a more robust and autonomous defence manufacturing base.

Since its launch in the 1980s, India’s Light Combat Aircraft (LCA) Tejas development by the Hindustan Aeronautics Limited (HAL) was riddled with difficulties. One of the main challenges was the Defence Research and Development Organization’s (DRDO) inability to develop the indigenous Kaveri engine. Since the Kaveri engine was unable to meet the necessary performance standards after years of research, the Kaveri engine was abandoned, and HAL was forced to rely on foreign engines like the General Electric (GE) F404 (Siddiqui, 2024). The development of engines was not the only technical challenge. There were many obstacles to overcome in order to integrate cutting-edge avionics, achieve ideal flight control systems, and guarantee structural integrity. The first flight took place in 2001, almost twenty years after the project’s inception, as a result of these delays.

Further impeding progress were supply chain constraints. Production schedules were thrown off due to delays in acquiring essential parts, such as engines from GE. The Indian Air Force’s (IAF) operational planning was impacted by these supply problems, which kept HAL from fulfilling delivery deadlines (Ganapavaram, 2025). Inconsistencies in policy and bureaucratic obstacles also played a part. Administrative delays brought on by complex procurement procedures and evolving defence policies slowed decision-making and hampered the program’s progress (IDRW, 2025).

However, despite early logistical and technological difficulties, India’s missile development program, led by the DRDO under the Integrated Guided Missile Development Program (IGMDP), has accomplished noteworthy milestones. The IGMDP was started in 1983 with the goal of creating a complete missile arsenal, which included the BrahMos (supersonic cruise missile), Agni (intercontinental ballistic missile), and Prithvi (short-range ballistic missile). India’s first domestically produced ballistic missile, the Prithvi series, underwent successful testing in 1988 and has been deployed in service since 1996 with multiple variants (DRDO, n.d.). Since the 1989 launch of the Agni-I, the Agni series has developed into long-range missiles with nuclear warheads, enhancing India’s strategic deterrence (Bobb et al, 1989). India’s strike capabilities were greatly increased when the BrahMos missile, a joint venture between Russia and India, became the fastest cruise missile in the world. These missile programs have placed India among the world’s top missile-capable countries, despite obstacles like a lack of domestic technology and reliance on international partnerships.

However, India has not yet achieved its goal of indigenisation. In 1992, a Self-Reliance Review Committee was constituted by the Ministry of Defence. The committee formulated a ‘10 Year Plan for Self-Reliance in Defence Systems’ through joint interactions between the Ministry of Defence and the three military services. According to the Vision Plan, the self-reliance index was expected to increase from 30% in 1994 to 70% in 2004. However, in March 2006, it remained stagnant at around 30-35% (Standing Committee on Defence, 2007).

India’s Policy Push for Defence Indigenisation

As discussed earlier, until 2010, India’s defence manufacturing sector remained largely stagnant, with limited efforts toward structural transformation. The sector was heavily dependent on imports, and domestic production was largely driven by state-owned enterprises, with limited contribution from the private sector in spite of liberalisation in the defence sector. Despite recognizing the need for self-reliance, policy inertia, bureaucratic hurdles, and lack of technological drive hindered meaningful progress. However, post 2014, a distinct shift in approach became evident. The government introduced a series of reforms aimed at breaking long-standing bottlenecks, fostering domestic capabilities, and promoting India as a global defence manufacturing hub. This period marked a departure from the earlier incremental changes, signaling a more comprehensive and strategic push toward self-reliance in defence manufacturing.

After the initial push on self-reliance in defence, it is the Make in India and Aatmanirbhar Bharat initiatives by the government in the last decade that have boosted the indigenisation of defence. The country’s defence industry is experiencing strategic transformation under these initiatives. India, which historically relied on foreign suppliers for cutting-edge military equipment, realised that in order to improve economic resilience and national security, it must increase domestic production and defence exports, and decrease its reliance on imports. These initiatives aim to modernise India’s armed forces while promoting domestic technological innovation through a mix of policy changes, investment incentives, and industry cooperation. In addition to pursuing strategic autonomy, India is establishing itself as a major player in the global defence export market by concentrating on the indigenization of military hardware, weapons systems, and vital defence technologies.

Various policy reforms were introduced by the Government of India that played a vital role in achieving self-reliance in the defence manufacturing sector. The Defence Production and Export Promotion Policy (DPEPP) 2020 aimed to achieve a turnover of ₹1,75,000 Crores —including export of ₹35,000 Crore—in Aerospace and Defence goods and services by 2025 (Ministry of Defence, 2020). Since 2014-15, India’s defence production increased substantially, rising 174% to ₹1.27 lakh crore in FY 2023–24. India’s drive for self-reliance strengthened in 2024–2025 when the MoD signed a record 193 contracts totalling over ₹2,09,050 crore, with a resounding 92% (177 contracts) going to the domestic industry. At the same time, India’s defence exports increased to ₹21,083 crore in FY 2023–24, a 30-fold increase over the previous ten years, and it currently exports to more than 100 nations. More than 14,000 and 3,000 items, respectively, have been made indigenous due to initiatives like SRIJAN and the Positive Indigenisation Lists. By 2029, India aims to achieve its goals of ₹3 lakh crore in defence production and ₹50,000 crore in defence exports (PIB, 2025).

Through the ‘Make’ Procedure, the Defence Acquisition Procedure (DAP) 2020 promotes domestic defence manufacturing. While Make-II permits Indian vendors to finance their own innovations with guaranteed procurement upon successful development, the government provides up to 70% (or ₹250 crores) in funding for the development of advanced defence equipment prototypes under Make-I. There are four Make-I projects underway at the moment, and 56 Make-II proposals have been accepted, 23 of which have been granted Acceptance of Necessity (AoN). Furthermore, since 2018, DRDO has started 233 projects pertaining to important defence technologies like artillery, missiles, radars, torpedoes, and autonomous underwater vehicles. 45 of these projects have been approved for integration into the military (PIB, 2021).

The Defence Acquisition Procedure’s (DAP) “Buy (Indian-IDDM i.e. Indigenously Designed, Developed and Manufactured)” category guarantees priority on acquiring domestic military hardware, which is further supported by a Negative Import List of 101 items that prohibits the importation of advanced defence systems like artillery, helicopters, and radars in order to promote domestic manufacturing. The SRIJAN Indigenisation Portal, introduced in August 2020, provides a platform for MSMEs and startups to create indigenous alternatives to imported defence components (PIB, 2021). However, given the challenges faced in developing the Kaveri engine, a complete ban on importing certain defence equipment should be reconsidered and evaluated strategically.

India’s Strategic Partnerships Policy, approved in May 2017, intends to increase private sector involvement in defence manufacturing in conjunction with DPSUs or OFBs. It was incorporated into the Defence Procurement Procedure (DPP) 2016 with the goal of decreasing reliance on imports while increasing efficiency, competition, and technology absorption. In order to fortify the defence industrial ecosystem, the policy focuses on acquiring fighter aircraft, helicopters, submarines, and armoured fighting vehicles through an open and organized process (PIB, 2018).

The Government of India, in 2020, also increased the Foreign Direct Investments (FDI) in the Defence sector. While the FDI continues to be 100% through the government route, it increased from 49% to 74% in the automatic route for companies seeking a new defence license (UNCTAD, 2020). This is a significant step, addressing long-standing concerns of foreign defence manufacturers, regarding ownership, control, and IP protection. This move can potentially attract fresh investments, expedite technology inflows, and encourage tier-1 and tier-2 vendors to establish operations in India.

Current Status of Domestic Defence Manufacturing

Significant progress has been made in India’s defence manufacturing sector owing to the combined efforts of state-owned enterprises and private sector companies. These entities have been instrumental in bolstering indigenous production capabilities.

A study suggests that privatized economies are approximately 145% as efficient as state-administered economies (Al-Obaidan, 2010). This trend holds true in the defence sector as well, where the involvement of private players has introduced greater efficiency, innovation, and accountability compared to traditional state-run models. The emergence of private players in India’s defence sector has increased competition, compelling public sector enterprises (DPSUs) to enhance efficiency, reduce delays, and improve cost-effectiveness. With private firms setting higher benchmarks in innovation and project execution, DPSUs face greater accountability in delivering quality defence systems on time. Additionally, competitive procurement processes and public-private collaborations ensure greater transparency and reduce inefficiencies in defence manufacturing.

State-Owned Enterprises (DPSUs) Leading Indigenization:

- AWEIL: India’s Advanced Weapons & Equipment India Limited (AWEIL) and Munitions India Limited, in collaboration with Russia’s Rosoboronexport & Concern Kalashnikov recently delivered 35,000 AK 203 assault rifles to the Indian Army. Production of these rifles is underway at an Ordnance Factory in Amethi, Uttar Pradesh, with full compliance to Make in India and Aatmanirbhar Bharat (The Economic Times, 2024).

- Hindustan Aeronautics Limited (HAL): The leading aerospace firm in India, HAL has played a key role in the creation and manufacturing of domestic aircraft. With its integration into the Indian Air Force to improve aerial combat capabilities, the Light Combat Aircraft (LCA) Tejas is a testament to HAL’s engineering prowess. HAL has also manufactured the Dhruv Advanced Light Helicopter (HAL, n.d.) to meet the needs of both the military and civilian needs. HAL promised to speed up fighter jet deliveries in February 2025, after the IAF expressed concerns about delays, which were partially caused by General Electric engine supply problems (Khan, 2025).

- Mazagon Dock Shipbuilders Limited (MDL): Focusing on building naval ships, MDL has made a substantial contribution to India’s maritime defence by building its own warships and submarines. One example of an initiative to lessen dependency on foreign technology is Project 75, where MDL builds submarines such as the INS Kalvari (The Week, 2025). Collaboration with Indian industries to develop and manufacture components further demonstrates MDL’s commitment to indigenization and increases naval defence self-reliance.

- Bharat Electronics Limited (BEL): With a focus on the creation of cutting-edge radar systems, electronic warfare gear, and communication devices, BEL has made a name for itself as a leader in defence electronics. Increased outsourcing to private sectors, cooperative research and development, and assistance for startups and MSMEs are some of the company’s efforts to promote Make in India. BEL recently delivered the 7000th Transmit/Receive Module to Thales for the radar on-board the Dassault Aviation Rafale (Thales Group, 2025).

Emerging Role of the Private Sector in Defence:

- Tata Advanced Systems Limited (TASL): Through partnerships with international aerospace giants like Lockheed Martin and Boeing, TASL has become a key player in the defence industry. The opening of India’s first private military aircraft manufacturing plant in Vadodara, Gujarat, in collaboration with Airbus Spain, is a historic accomplishment. Tata Advanced Systems will produce 40 fly-away C-295 transport aircrafts for the Indian Air Force (Airbus, 2024). These first Indian-made aircrafts, anticipated by 2026, represent a major turning point in the private sector’s involvement in defence manufacturing.

- Larsen & Toubro (L&T) Defence: L&T Defence has expanded its range of business to encompass aerospace projects, artillery units, missile components, and naval systems. Along with producing the Polar Satellite Launch Vehicle (PSLV) in partnership with HAL, the company has played a significant role in manufacturing essential components for India’s space missions. The first privately constructed PSLV launch is planned in 2025, underscoring L&T’s growing involvement in the space and defence industries. (Kumar, 2025)

Growth in Indigenous Production:

- Increased Domestic Procurement: In March 2024, the Ministry of Defence (MoD) signed five significant capital acquisition contracts totalling 39,125 crore, demonstrating the MoD’s strong commitment to domestic procurement. These contracts, which support the drive for defence production to become more self-reliant, include the purchase of missiles, radars, weapon systems, and aero engines from Indian businesses. (Shukla, 2024)

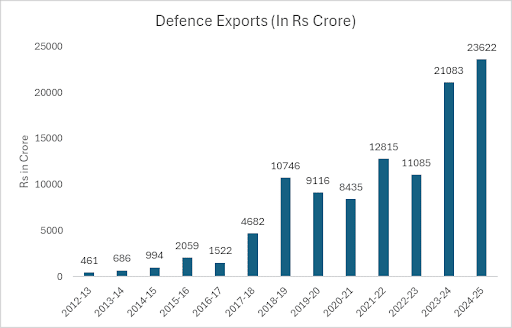

Increase in Defence Exports: In the fiscal year 2023–2024, India’s defence exports reached ₹21,083 crore, marking a remarkable upswing. The year 2024-25 saw a surge to record high of ₹23,622 crore, a 12.04% increase from the previous year (The Hindu, 2025). Source: Ministry of Defence Annual Reports (2013-14 to 2022-23)

Source: Ministry of Defence Annual Reports (2013-14 to 2022-23)

The graph above charts India’s defence exports from 2012–13 to 2024–25. The absence of export data in Ministry of Defence annual reports prior to 2012–13 reflects the limited policy focus on defence exports in earlier years. The upward trend of the graph demonstrates the success of programs meant to encourage domestic production as well as the increasing international recognition of India’s defence manufacturing capabilities.

These developments underscore India’s commitment to achieving self-reliance in defence manufacturing and its emergence as a significant player in the global defence industry.

Case Study: Adani Defence & Aerospace

One of the major private companies spearheading India’s transition to an indigenous defence industry is Adani Defence & Aerospace. The company is actively involved in manufacturing advanced defence equipment, including unmanned aerial systems (UAS), counter-drone solutions, ammunition, and missile systems.

Major Projects and Collaborations

To indigenise unmanned aerial platforms, Adani Elbit Advanced Systems India Limited—a joint venture between Adani Defence & Aerospace and Elbit Systems, Israel—built the first private UAV manufacturing complex at Adani Aerospace Park in Hyderabad. The Hermes 900 is a modern, combat-ready multi-role unmanned platform with an endurance of 36 hours, payload capacity of 420 kg, altitude of over 32,000 feet i.e. more than 10 kilometres, with applications across civil, military, and homeland security. The Adanis have started to export the Hermes 900 Unmanned Aerial Platform to international customers from the sole Hermes 900 manufacturing facility outside Israel (Adani Defence & Aerospace, 2020).

Considering the increased use of drones in modern warfare, it is imperative for countries to have anti-drone systems. Under a PPP model, Adani Defence & Aerospace, in collaboration with DRDO, recently unveiled Vehicle-Mounted Counter Drone System at Aero India 2025 expo. Mounted on a 4×4 vehicle, this anti-drone uses a high-energy laser system for precision drone neutralisation, a 7.62 mm gun to respond to aerial threats, and advanced sensors, including radar, electro-optical systems, and jammers for real-time detection, tracking, and neutralisation of targets within a 10 km range. By integrating multiple counter-drone technologies into a single platform, the system ensures rapid response, enhanced operational flexibility, and robust protection (Adani Defence & Aerospace, 2025).

Contribution to India’s Defence Indigenization

The Indian Navy and the Indian Army recently inducted two UAVs (Unmanned Aerial Vehicles) manufactured by Adani Defence & Aerospace, marking a step towards self-reliance in drone technology. Drishti 10, an all-weather UAV, is designed for military reconnaissance, surveillance, intelligence gathering, and search-and-rescue operations, enhancing real-time situational awareness. Equipped with advanced sensors and communication systems, it strengthens border monitoring and maritime security. While the numbers are currently limited, this induction signals India’s push to reduce dependence on imported UAVs and build a robust domestic drone manufacturing ecosystem to support long-term defence modernization. (Business Line, 2024)

In February 2024, Adani Defence & Aerospace unveiled South Asia’s largest ammunition and missiles complex in Kanpur, Uttar Pradesh. In the 500 acres land, the facility will produce small, medium and large calibre ammunition for the armed forces, paramilitary forces and police. The facility has started rolling out small calibre ammunition, starting with 150 million rounds estimated at 25% of India’s annual requirement. The facility will also manufacture 12 types of guns in tie-up with Israel’s Elbit System. The facility will also produce anti-aircraft movable rockets, hand grenades, mortars, artillery shells, etc. in addition to strengthening India’s self-reliance in defence production, this facility is expected to create approximately 4,000 direct and indirect jobs, strengthening the local economy while contributing to national security. (Sharma, 2024)

Overall, Adani Defence & Aerospace represents the evolving role of India’s private sector in defence manufacturing, bridging critical capability gaps while fostering self-reliance. Their shift from mere domestic assembly to end-to-end indigenous production highlights the true essence of indigenisation of defence manufacturing. By integrating advanced defence technologies with local manufacturing, Adani Defence is not only strengthening India’s military preparedness but also creating an ecosystem for future innovation. As India emerges as a defence exporter, the success of firms like Adani Defence will determine the extent to which the nation can transition from being a major importer to a trusted global supplier of advanced defence systems.

Challenges and Way Forward

Ease of Doing Business

While India has taken significant strides in Ease of Doing Business by improving its ranking from 134th in 2013 (World Bank, 2014) to 60th in 2019 (World Bank, 2020). However, there are many issues that still remain. India’s Commerce Minister Piyush Goyal’s statements about Indian startups only focusing on delivery apps recently led to big controversy. In a response to the minister, a semiconductor entrepreneur highlighted serious concerns about the ease of doing business in India’s high-tech and defence sectors. Despite building a profitable deep-tech startup serving clients in the US and EU, the founder said attempts to engage with Indian government departments, including MeitY and the defence establishment, were met with bureaucratic apathy and indifference. He discussed the unwillingness to commit to procurement, which discourages startups from investing time and capital in unproven domestic opportunities. The founder also shared his experience of having a government application stuck for over two years, only to be returned with a request for additional documents—after which the process would restart from scratch (Business Today, 2025).

A 2022 report on Ease of Doing Business in India’s Aerospace and Defence Sector by the UK India Business Council highlights that companies in the aerospace and defence sector still face difficulties in acquiring land, securing infrastructure support, and navigating overlapping regulatory jurisdictions between the central and state governments. Moreover, the lack of a single-window clearance mechanism tailored for defence manufacturing leads to firms interacting with various departments — ranging from the Ministry of Defence to Ministry of Home Affairs — each with its own timelines and procedures. These procedural frictions increase the cost and uncertainty of doing business in the sector, thereby discouraging private investment, particularly from start-ups and MSMEs. Unless these sector-specific challenges are resolved through streamlined regulatory frameworks and better implementation mechanisms, India’s broader goals of defence indigenisation and self-reliance will remain constrained despite macro-level policy improvements (UKIBC, 2022).

These experiences illustrate the procedural inefficiencies, lack of institutional responsiveness, and resistance to private sector collaboration that continue to challenge India’s ambitions for indigenisation in critical sectors like semiconductors and defence manufacturing. It is high time government officials and ministers acknowledge the inefficiencies, and work together to resolve the issues.

Technological Gaps and R&D Limitations

Research and Development (R&D) is a bedrock of any technological innovation. If India aspires to indigenously manufacture and fulfil its defence needs, it is pertinent to have a good R&D programme in place. It is particularly important to spend more on R&D as it fosters innovation that benefits both military and civilian needs. Called the ‘dual usage of technology’, the technological advancements in defence manufacturing (e.g., AI, aerospace, semiconductors, etc.) have commercial applications in industries like telecommunications, healthcare, and transportation as well.

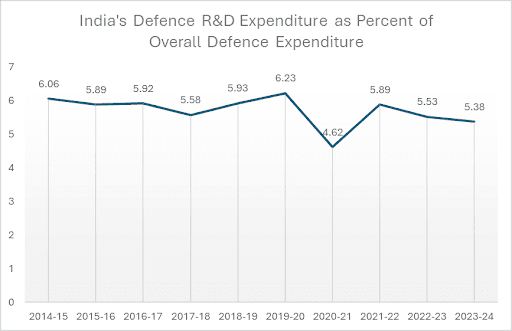

Source 2: Standing Committee on Defence 2023

Source 2: Standing Committee on Defence 2023

As the graph shows, India has consistently spent somewhere between 5.5% to 6.5% of its overall defence expenditure on R&D (Standing Committee on Defence, 2023). When it comes to R&D spending, India falls far behind the giants of the world, and needs to significantly increase its allocation and expenditure of budget for research and development.

While the DRDO is doing well with the resources at its disposal, there is an urgent need for India to step-up its R&D in defence. An analysis of 178 DRDO projects by the CAG revealed that 119 projects failed to meet their original timelines, with 49 exceeding their initially planned duration. Some projects were deemed successful despite not fulfilling key objectives or parameters. The Standing Committee on Defence highlighted that delays in DRDO projects have become a recurring issue, resulting in cost overruns and depriving the armed forces of essential capabilities (Standing Committee on Defence, 2023). There is an urgent need for the government to review DRDO’s internal mechanism to ensure there are no delays and cost overruns in the system.

Dependence on Foreign Raw Materials & Components

As mentioned earlier, with cases such as failure of Kaveri engines, it is clear that India still does not have capabilities to produce indigenous jet engines. The government needs to give a stronger push to the PPP model in defence manufacturing to ensure the best of both can be leveraged in the quest of self-reliance. Another huge roadblock is the import of electronics and semiconductors, impeding the development of fully indigenous defence equipment. Developing a robust semiconductor manufacturing ecosystem is essential to achieve self-sufficiency in defence electronics.

Slow Bureaucratic Processes & Procurement Delays

Mukherjee (2011) states that the generalist system of administration – where bureaucrats are rotated amongst different ministries – leads to bureaucrats who lack the knowledge of how the defence system works being at the helm of affairs. The author argues that “Civilians in the MoD lack the capacity to arbitrate among competing parochial service interests or even evaluate functional issues like long term defence planning, military capabilities and strategies.” Additionally, lengthy defence procurement cycles and delays in finalising defence contracts have significant implications for both project execution and investment. The procurement process in India is often bogged down by bureaucratic hurdles, multiple layers of approval, and slow decision-making, resulting in extended timelines for acquiring essential defence equipment. These delays hinder project execution, leaving the military with outdated technology and impacting operational readiness. To address these challenges, the defence procurement process should be streamlined with clearer timelines and reduced bureaucratic delays. Establishing a dedicated defence procurement board could expedite contract finalization and ensure transparency. Additionally, incentivizing private sector participation through faster approvals and long-term partnerships would boost investment and innovation in the defence sector.

Limited Export Market for Indian Defence Products

India’s defence exports have seen growth, yet they remain modest compared to global leaders. Challenges such as limited global partnerships, and a lack of aggressive marketing strategies result in limited expansion into international markets. Streamlining export procedures and reducing bureaucratic red tape can facilitate smoother transactions. Establishing dedicated agencies to oversee defence exports can provide strategic direction. Additionally, active participation in international defence exhibitions and forming strategic alliances can enhance India’s global footprint. Government-backed incentives and credit lines for foreign buyers can further promote Indian-made arms.

Enhancing Private Sector Participation

The private sector’s involvement in defence manufacturing in India is often hindered by restricted access to capital and stringent regulations. Easing access to capital through defence-specific financial instruments and providing tax incentives can stimulate private investment. Simplifying the approval process for defence projects and ensuring a level playing field between public and private entities will encourage more private sector participation. Facilitating joint ventures with global defence Original Equipment Manufacturers (OEMs) can also bring in advanced technologies and best practices.

Expanding Indigenous Manufacturing Infrastructure

While initiatives like the defence industrial corridors in Uttar Pradesh and Tamil Nadu aim to bolster manufacturing, challenges such as inadequate infrastructure and supply chain inefficiencies persist. Accelerating the development of these corridors with impeccable infrastructure and seamless connectivity can attract investments. Implementing skill development programs tailored to defence manufacturing will create a competent workforce. Strengthening domestic supply chains by supporting local suppliers and integrating them into the defence manufacturing ecosystem can reduce dependence on foreign raw materials.

Conclusion

India’s journey toward defence indigenization has witnessed significant progress, transitioning from heavy import dependency to self-reliance in critical defence segments. With active participation from state-owned enterprises and private players, indigenous manufacturing capabilities have expanded considerably. However, challenges such as technological gaps, limited R&D funding, and bureaucratic inefficiencies in procurement continue to hinder rapid advancements. At the time of writing this paper, a young IAF pilot lost his life due to his Jaguar aircraft crashing. A similar crash happened in March 2025 (Hindustan Times, 2025). There have been questions about why the IAF is still using the Jaguar, which first entered its fleet in the 1970s. The engine of the Jaguar is outdated, and critically underpowered (Tyagi, 2025). The fleet of Jaguars were retired by France and the UK in 2005 and 2007 respectively, and went on to build their own jets (Tiwari, 2025). India on the other hand continues to use the age-old Jaguars. It is high time India focuses on building its own aircrafts and retires the Jaguars and other such obsolete aircrafts at the earliest. It is precisely at such instances that one realises the importance of self-reliance in defence manufacturing.

Addressing these issues will require strategic policy interventions, including increased investments in defence R&D, fostering global collaborations for technology transfer, and streamlining regulatory processes. Additionally, to prevent brain-drain and retain top talent, the government should offer incentives, research grants, and career opportunities to skilled professionals, encouraging them to contribute to India’s defence ecosystem. Looking ahead, India has the potential to emerge as a global defence manufacturing hub, bolstered by initiatives such as defence industrial corridors, export-driven strategies, and enhanced private sector participation. By implementing forward-thinking policies and leveraging its growing capabilities, India can strengthen its defence sector, reduce reliance on imports, and position itself as a key player in the global arms industry.