Abstract

A vast section of India’s large population relies on social welfare schemes to supplement their livelihoods and well-being. The MGNREGA scheme is considered one of the largest such social welfare schemes in the world, in terms of beneficiaries covered. Over the last couple of years, the scheme has been updated with digital processes which were made mandatory in 2023. This paper discusses the new mandatory mobile application based attendance system (NMMS app) for MGNREGA workers, which requires two photographs of the worker to be uploaded twice a day in the morning and evening, at the worksite, in order to be marked present and receive payment. There have been widespread concerns and protests by workers’ groups regarding the app, with numerous instances of missed attendance, glitches in the app, issues with connectivity and resulting unpaid work. This paper sets out to explore the claims made by the protesting workers’ and civil society groups. The discussion finds that in the year preceding the decision to make the app mandatory, there existed several challenges of implementation and usage across the country. Almost half of the eligible worksites do not use the app, and there appear to be several challenges for the remaining worksites that do. The paper finds that even when attempts to implement the app have been made, issues of connectivity, device ownership and glitches in the app itself have resulted in low-to-no usage. Finally, we find a big implementational gap in the practice of uploading photographs on the app, whereby uploading the second set of photographs in the evening has been a severe challenge due to worker unavailability and livelihood concerns, with a large number of attendance days that are missing both sets of photos. In this context, the paper argues that the burden of digitisation in MGNREGA has been passed on to the worker, without accounting for regional, financial and social challenges that affect digital literacy and usage among the socio-economically vulnerable. Finally, we argue that the condition of making the app mandatory without accounting for the challenges in the preceding year indicates a trend of ultimatum-based governance, wherein states with differential capacities are expected to catch up at the same pace, even while social welfare is negatively affected.

Keywords:

social security, social welfare, app-based attendance, digitisation, connectivity, workers’ rights.

1. Introduction

In recent years, social policymaking and policy orientation in India have found digitisation and citizen interaction with digital technology at their conceptual core. Increased penetration of digital services and mobile technology in India, and globally, has accompanied a discussion on the leveraging of such technologies for more targeted policymaking and functioning (EY India, 2023). However, the rise of digital technologies within India has not been uniform and has exposed many inequalities in the experience of digital services across lines of class, caste, gender and geography (Chandola, 2022). An aspect of this digital inequality can be seen in the interaction between workers’ rights and digitisation of processes that deal with the workers’ ability to reap the benefit of meaningful work. The recent developments in The Mahatma Gandhi National Rural Employment Guarantee Act 20051 [MGNREGA] scheme has raised concerns about overlooking workers’ well-being, while prioritising digitisation of the scheme. Since February 2023, civil societies and workers’ groups, such as the NREGA Sangharsha Morcha, have been demanding the rollback of the new mandatory attendance and payment system, highlighting how the government prioritised an arbitrary digitisation over addressing real and persistent challenges to the scheme (Nair, 2023a). Recently, two major changes to the scheme were announced by the Indian government – the establishment of mandatory attendance through a mobile application – National Mobile Monitoring System [NMMS] and the mandatory linking of Aadhar details with worker’s bank accounts and job cards in order to receive MGNREGA payments (The Wire Staff, 2023) Simultaneously, the budget for MGNREGA in 2023, has been cut by 33% compared to the previous year, resulting in significant backlash from concerned stakeholders (Bhatnagar, 2023; Nair, 2023b).

The MGNREGA is considered to be a flagship scheme of the Indian government and aims to provide at least 100 days of employment to enhance the livelihood security of rural households. Since its inception in 2005, the scheme has covered a vast section of the Indian population, and in 2015, the World Bank ranked it as the world’s largest public works program providing social security (World Bank, 2015). The most vulnerable sections continue to seek work under this scheme, and the scheme played a critical role in safeguarding the incomes of a portion of India’s vulnerable population during the Covid-19 Pandemic (Basole & Narayanan, n.d). The scheme combines the need for the building necessary public infrastructure while also prioritising the employment of those most in need. The scheme is predominantly administered through the Panchayati Raj Institutions [PRIs] to ensure local cohesion and smooth functioning, and the overall year-on-year execution is one that requires significant cooperation between the centre and states (PIB, 2022a).

2. Methodology

The state-wise analysis and comparison has been done using the top 20 states by population, as per the 2011 census (IndiaCensus n.d.), which has left out North-Eastern States and Union Territories. This is predominantly due to the relatively lower number of MGNREGA worksites and allied data in these regions, as compared to the top 20 states. The national averages for all graphs however (unless specified in the respective section), have been calculated using all states and Union Territories. Thus, the analysis should be interpreted in an indicative and comparative manner which looks at the performance of densely populated states against each other, and the national average.

An important note to keep in mind during the analysis, is that the discussion on West Bengal has been moved to a subsection in the later half of the paper, and not discussed along with the graphs. This is due to little to no MGNREGA work being done in West Bengal in 2022-23 (Shagun, 2023; Anand, 2023), and funds being halted for the state. However, the state has been included in the comparative analysis, in order to maintain the calculation using the top 20 most populous states, and to make this analytical approach future-proof, for when MGNREGA is resumed in West Bengal. Interestingly, the exclusion of West Bengal would have made the averages arguably worse, and the low to no MGNREGA work in West Bengal has marginally increased the average (however, it is not a significant difference). Thus, some charts on their own may show efficient implementation in West Bengal, but should not be interpreted that way, without contextualizing against the later discussion on West Bengal.

Finally, there are likely to be developments to the scheme, the NMMS app and the ABPS system in the months succeeding this paper. In such a case, the paper will be modified accordingly to reflect the updates to the scheme.

3. Initiation of Mandatory Processes to MGNREGA in 2023: App-Based Attendance and Aadhaar Based Payment System

In late 2022 and early 2023, the Ministry of Rural Development [MoRD] called upon states to implement the following mandatory changes to the MGNREGA scheme (PIB, 2023): The Union Government declared that from 1st January 2023, the attendance of MGNREGA workers would be marked only through the National Mobile Monitoring System [NMMS] app. Later, the MoRD declared that from 1st February, all MGNREGA wage payments would be made only through the Aadhaar Based Payment System [ABPS]. Upon backlash from states over the mandation of the ABPS payment system, the deadline was later extended to 31st March. It was extended once again to 30th June, upon sustained backlash. According to the government, both these procedures were introduced in order to increase transparency in functioning and address issues of corruption within MGNREGA. Both these changes have come against the backdrop of a 33% cut in the Budget Estimate for MGNREGA for 2022-23 (Bhatnagar, 2023).

It is important to note that these are not procedures that were suddenly introduced in 2023 – they have been operational for a while, in tandem with other processes that were in place to achieve the same results. Thus, the concerned processes were not mandatory when it came to completing the end-to-end procedure of finishing the work , and then receiving wages for the work done. Therefore, the recent developments are not the introduction of new processes, but the mandation of processes that were introduced before. The NMMS App was introduced in May 2021, while the ABPS system has been in place since 2016. This merits attention for the following reasons: first, there have existed considerable opportunities, along with available data, to discuss and analyse the operation patterns, challenges, and attitudes regarding the NMMS app and ABPS system since their inception, and second, the rationale for their recent mandation must be then contextualised against how many of the related issues were addressed or acknowledged before the recent undertaking towards mandation.

This paper will focus on the NMMS app, and discuss its mandatory introduction in the context of state capacities, implementation issues and workers’ rights. While a discussion on ABPS will be included, it is not the focus of the paper. This is because the ABPS, while being another mandatory digital process, is not a part of the workers’ day-to-day process of engaging with MGNREGA work and the worksite. The NMMS app, however, is a recurring need and is required each and every time a worker is at a MGNREGA worksite. Thus, the burden of execution of mandatory attendance is recurring ,granular, and likely to influence the daily choices and capacities of workers to interact with the worksite and with the MGNREGA administration at the site. The ABPS, while it has its problems and excludes a large section of workers from receiving payments (Dreze, 2023, also discussed in section 6), is a process that occurs on the back end, involving multiple stakeholders in its implementation. Even then, however, the predominant burden does remain on the workers, to initiate and go through the steps that ensure their ABPS eligibility.

The protests surrounding MGNREGA are not arbitrarily against any new technological developments. The main concern about the app is not the principle of mandatory attendance itself, but the method chosen by the government to implement it. The workers have reported several instances of missed attendance even when work has been done, claiming that there are glitches in the app. It is important to consider that these are concerns of those who have diligently used the app and have obeyed the rule. Of course, there is also a whole section that has been unable to use it at all, failing to comply even if they want to. Such instances have occurred due to device incompatibility, poor network and other issues of implementation. Specifically, the NMMS app was introduced with the assumption that all workers, even those in weaker socio-economic areas, own and know how to operate smartphone devices. In the event that someone does not have a smartphone, it is expected that they will procure it, somehow.

This paper will thus explore the concerns of the protesting workers and discuss challenges faced by them in using the NMMS app. Using the performance and functioning of the app, and the background in which mandatory app-based attendance was initiated, this paper will explore the rationale behind the move, against the perceived benefit of the move so far. The discussion will highlight two major concerns – one, the NMMS initiative is in a state of implementation without benefit, where the move fails even when it is used, and in many cases, makes it difficult for someone to use it in the first place, and second, different states have different challenges and capacities vis-a-vis digitisation and workers’ comfort, and a blanket mandate of this initiative undermines the spirit of federal deliberation and well-being.

Finally, it is important to highlight once again, that the discussion reveals an arbitrary rejection of the app in very few situations. In most cases, the data actually indicates that states have tried to implement it. The issues with the app, therefore, are exogenous, and not in the control of the stakeholder community, i.e, the workers, to fix. It is here, that a trend of governing through ultimatums emerges, where a social security scheme aimed at welfare, prioritises digitisation at the cost of workers’ concern and capacity.

4. Functioning and Performance of the NMMS App: Low Usage, Gaps in Attendance and Issues of Malfunction

The NMMS App is a mobile application that requires the user to own or have access to a smartphone. The app is used to collect attendance at worksites and the mates at the worksites are the only ones allowed to use this app. In May 2021, this process was made mandatory for worksites with more than 20 workers in the muster roll, but since January 1st, 2023, it has been expanded to include all workers at a worksite. The NMMS app replaces the previous process where attendance was collected manually by mates at worksites for works which had less than 20 workers present (Nair, 2023a).

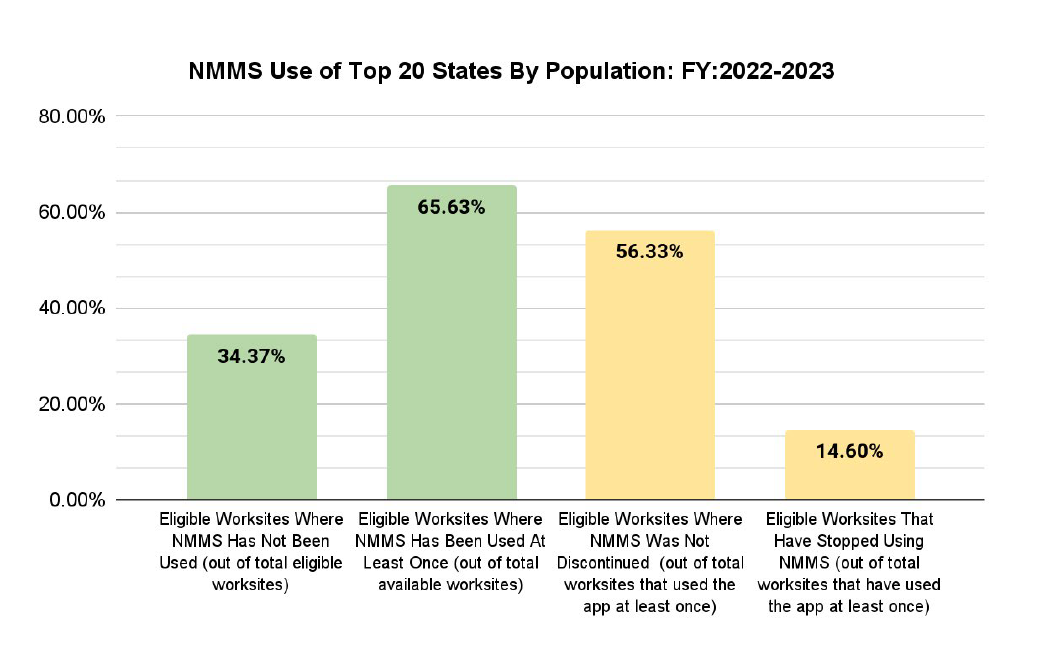

The app has received serious backlash from civil activists and workers’ rights groups across the country. As a result, since 13th February, workers from West Bengal, Jharkhand, Bihar, Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan and Chhattisgarh have been protesting at New Delhi in batches, against the app (Butani, 2023). Since May 2022, several challenges with the app have emerged that have led to worksites giving up the use of the app entirely, even after having used it once. The usage of the app over the past year is depicted in Chart 1, which shows the eligible worksites and their usage of the app. Before the initiation of mandatory attendance from January 2023, in 2022, only worksites with 20 or more workers were eligible to be using the app. In that year, over a third of worksites have not used it even once, and almost 15% of worksites have used it briefly and have subsequently stopped using the app.

Chart 1. Source: Calculated and compiled by the author using the all India R21.10 report (as of 12th April, 2023) from the MGNREGA website, managed by the Ministry of Rural Development. This data depicts the use for the top 20 states by population (according to the 2011 census).

While the data suggests that about 66% of eligible worksites have used the app, these refer to worksites that have used the app at least once, in an entire year. Thus, this fraction is not indicative of the efficiency of the app and neither is it indicative of its sustained use. Indeed, the rough 15% that have stopped using the app are derived from the 66% that have used it, which implies that the real worksite usage percentage is much less. What is worth noting here, is that the consistent instances of glitches and issues with the app arise from within this 66%, thereby suggesting that while 66% have used the app, the effective continued use is much less at 56.33%. Those protesting have cited instances where they have missed days of attendance even after putting in the work, due to glitches in the NMMS app (Butani, 2023). This trend, against the remaining 46% that have never used the app or have stopped using it, aligns strongly with the experience being relayed by the protesters in New Delhi.

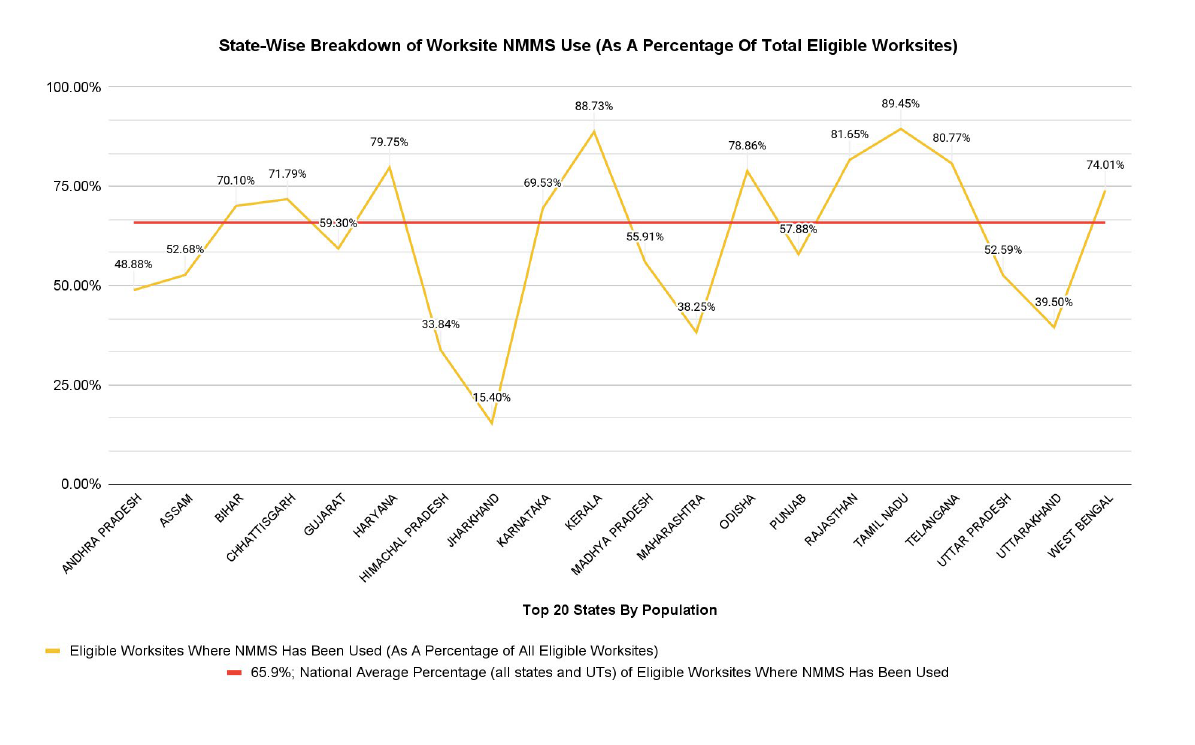

Chart 2: Source: Calculated and compiled by the author using the all India R21.10 report (as of 12th April, 2023) from the MGNREGA website, managed by the Ministry of Rural Development. This data depicts the use for the top 20 states by population (according to the 2011 census).

The app usage has varied considerably across states as well, as can be seen in Chart 2. This chart depicts the worksite usage percentage of the NMMS app for the top 20 states by population (according to the 2011 census), compared against the national average usage percentage of 65.9%. Here, the condition of some states,such as Maharashtra, Jharkhand, Uttar Pradesh and Madhya Pradesh, is especially dire. Uttar Pradesh has been one of the most funded states for this scheme, receiving the most funds of all states in 2020-2021 (Dominique, 2021), and has been consistently high on the list for prior years as well (PIB, 2022b). The state-wise variation in worksite usage indicates that a simple blanket approach to digital implementation is likely to affect different states adversely, in different ways. Thus, targeted troubleshooting with a one-size-fits-all approach to improving implementation may prove difficult.

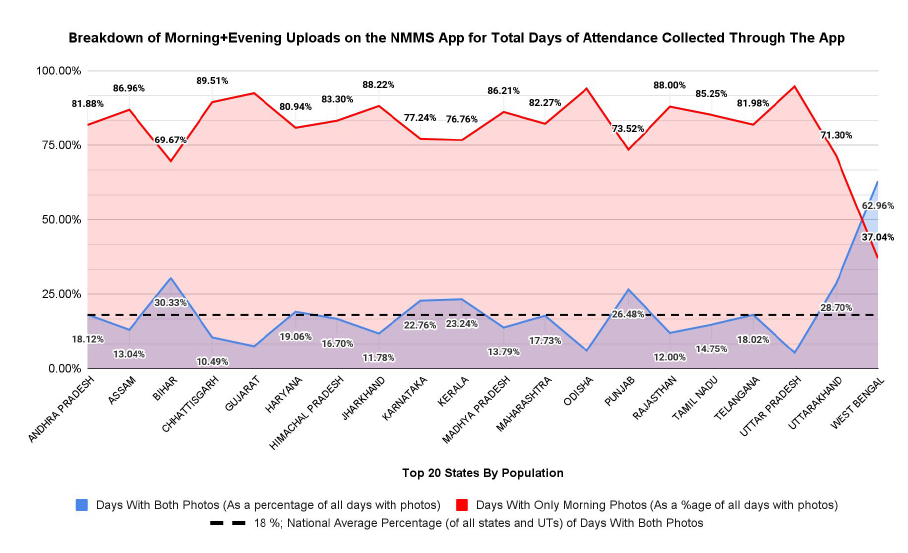

Besides poor app usage across the country, whenever the app has been used, one of the major concerns has been the applicability of the principle of photograph-based attendance itself. The attendance process involves the mates taking two time-stamped and geo-tagged photographs of the workers at the worksite, and uploading the pictures on the NMMS app. The first picture shows the worker during the 6:00 to 11:00 a.m. schedule and the second shows the worker during the 2:00 to 6:00 p.m. schedule. In case only one picture or both pictures of the worker is not there, the worker is marked absent for that day. Ideally, this means that there should be an equal number of days with both photos, or rather, the same number of morning and evening photos. The reality however, is very different, as can be seen in Chart 3.

Chart 3: Source: Calculated and compiled by the author using the all India R21.11 NMMS Attendance status For FY:2022-2023 (as of 12th April, 2023) from the MGNREGA website, managed by the Ministry of Rural Development. This data depicts the use for the top 20 states by population (according to the 2011 census).

Chart 3 shows the state-wise breakdown of days in which NMMS was used to mark attendance in 2022-2023. Data from the top 20 states by population has been used (as per the 2011 census). Before we proceed with the discussion, there are some important limitations that need to be kept in mind regarding the data. The original data gives numbers for the following parameters: total days on which attendance was taken using the app, total number of morning photos and the total number of both (morning + evening) photos. However, the numbers for the first two parameters are exactly the same, for each state. This possibly implies that the report interprets a morning photograph as a day in which attendance has been taken through the app. Thus, for the sake of analysis, the data has been broken into total days on which attendance has been taken, and total days on which both photos are present (as the day of attendance is determined backwards by the existence of photographs. Thus, the number of “both photographs’’ in 2022-2023 basically implies the number of days with both photographs in 2022-2023). Thus, the existence of a morning photo counts as a day, implying that the data for the first parameter is not independently provided. This is important as it means that any day of work, anywhere in the country, in which a morning photograph was not taken does not count as a day in which the NMMS app was used to take attendance.

In Chart 3, the blue line represents the percentage of days on which both photos were uploaded to the app, and the red line represents days on which only the morning photo was uploaded to the app. As discussed previously, ideally, the blue line and red line should be identical as the purpose of the app is to have both photographs as a marker of workers’ attendance. However, the gap between them indicates significant misses with the secondary photograph to complete a worker’s attendance, which has not been uploaded in many instances across the country. The black dotted line indicates the national average percentage of total days with both photographs as of total days of NMMS attendance (for all states and UTs), which stands at a staggering low of 18%. The red-coloured section between the two lines indicates the number of days with missing evening photos.

The above aligns strongly with the experiences of those protesting against the app. Most of the concerns have been regarding how even when a picture is taken, glitches with the secondary picture result in that day’s attendance going missing (Khan, 2023). A significant source of these misses may be linked to most MGNREGA workers completing their allotted task during the morning session, and then leaving to find more non-MGNREGA work (Paliath & Dutta, 2023). With the new system of geotagged photographs, a worker is forced to be available for the evening session, even if there is no work to be done, just so that the photograph can be taken. Many workers thus end up missing the evening photograph, as can be seen in Chart 3. In many cases, it is reported that the app is glitchier in the second round of photographs (Inzamam, 2023).

Further, another major concern of the workers has been the requirement of personal mobile devices for the NMMS app to be used (Khan, 2023; Paliath & Dutta, 2023; Butani 2023). The MGNREGA mate, another worker-cum-supervisor at the worksite, is required to get their personal device registered for the NMMS app to be used. However, many workers are unable to procure, or do not have a functioning device, but are forced to fall back on borrowed or faulty devices in order to get work (ibid). In several cases, a worksite is not in an area with proper network coverage, and the upload of photographs fails (ibid). Chart 4 shows exactly this, where we see that the number of devices that have used the app are significantly less than the number of devices that have been registered to use the NMMS app, and this is true for all states depicted. This implies significant misses when it comes to device efficiency. It is highly likely that the experience of the protesting workers are significant – the shortfall in used versus registered devices implies that either devices are incapable of using the app, are not in areas of proper network, don’t belong to the workers, or a mixture of more than one of these reasons.

Chart 4: Source: Calculated and compiled by the author using the all India R21.6 NMMS Implementation Status Report For FY:2022-2023 (as of 9th May, 2023) from the MGNREGA website, managed by the Ministry of Rural Development. This data depicts the use for the top 20 states by population (according to the 2011 census).

Chart 5: Source: Calculated and compiled by the author using the all India R21.6 NMMS Implementation Status Report For FY:2022-2023 (as of 9th May, 2023) from the MGNREGA website, managed by the Ministry of Rural Development. This data depicts the use for the top 20 states by population (according to the 2011 census).

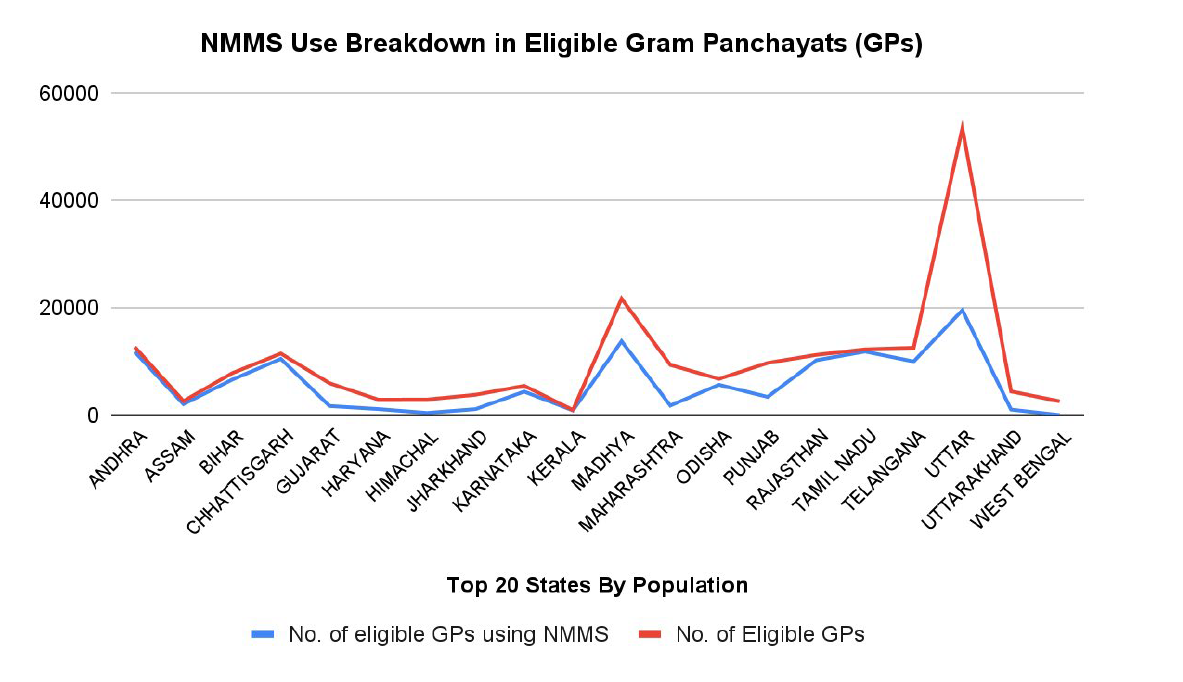

Comparing Chart 4 against Chart 5 presents an interesting picture – the gap between state-wise total eligible Gram Panchayats [GP] that have used the app is much less than the gap between registered devices that have actually been used. This is interesting as it indicates that while eligible GPs that have used the NMMS app are greater, and coincide relatively closely with the total state-wise eligible GPs, this GP-wise usage has not translated into more devices being used, even after they have been registered. Take for example, the case of Andhra Pradesh, which has one of the largest gaps between used versus registered devices, but the gap is almost non-existent when it comes to eligible GPs that have used the app. A similar situation arises for Kerala, where the gap in eligible GPs using the app is insignificant, but a wide gap exists between used versus registered devices. The condition of Uttar Pradesh is dire and paints a poor picture of proponents of the app – while the state has the most absolute number of GPs using the app, it has a significantly higher number of eligible GPs than other states, leading to a large gap of almost 3 lac eligible GPs not using the app.

5. Implementation Without Effective Benefit, and the Additional Burden of ABPS

| Parameter | Parameter | Status |

In-Paper Depiction

|

|

Worksite Eligibility

|

Eligible worksites that have not used the NMMS app even once. | 34.37% | Chart 1 |

| Eligible Worksites That Have Stopped Using NMMS (out of total worksites that have used the app at least once) | 14.60% | Chart 1 | |

| National Average Percentage (all states and UTs) of eligible worksites that have used the app, out of total eligible worksites. | 65.90% | Chart 2 | |

| Days With Both Pho- tos on The NMMS App | National Average Percentage (all states and UTs) of days in which both photos were uploaded on the NMMS app, as a percentage of all days with photos uploaded on the app. | 18% |

In Discussion Section 4.2

|

| Device Use | National Average Percentage (all states and UTs) of used devices, out of all registered devices. | 26.99% |

In Discussion Section 4.2

|

| GP-Use | National Average Percentage (all states and UTs) of eligible GPs that have used the app, as a percentage of all eligible GPs. | 58%. | Chart 5 |

Table 1: Summary of Findings So Far.

5.1. The Case of Rajasthan: Peculiar Choice as a Pilot Study State and Some Key Contradictions

Before we proceed, the state of Rajasthan merits a special mention. According to the Minister of State for Rural Development, Sadhvi Niranjan Jyoti, a pilot testing was conducted in Alwar, Rajasthan before taking the decision to launch the app (Sharma, 2023). Interestingly, some peculiar trends emerge in terms of NMMS performance in this state. Rajasthan is the state with the most number of registered devices, and the most number of used devices, in absolute terms. At the same time, it has a large gap between used devices out of registered devices at almost 37%, and falls below the national average for days with both photos, at 12%. At the same time, almost 92% of eligible GPs and almost 82% of its eligible worksites have used the NMMS app, both rates considerably higher than other states. These contradictions within Rajasthan act as a minor case study for the app, and indeed, the MoRD itself considers Rajasthan as a case study. Rajasthan presents a clear case where efficiency has not accompanied implementation, the app has been used and GPs are aware – and yet there are severe gaps in functioning. One would expect the benefits of this app to be clear, especially for a pilot testing state, and one with high usage. However as the data suggests, the reality is different. This reaffirms the concerns of the protesters, the app does not work even when it is used, and used abundantly. It is further peculiar, then, that pilot testing in a single district in Rajasthan was justification enough to declare roll-out of the app. There remains insufficient response or data about the results of this pilot testing, why Rajhasthan was chosen, and why the findings were generalised for the rest of the country.

5.2. Contradictions in Usage Rates: Worksites, GPS and Devices

Further, the contradictions in usage are clear. The national average percentage (all states and UTs) of eligible GPs that have used the app, out of all eligible GPs, stands at about 58%. The national average for eligible worksites that have used the app stands at almost 66%. In sharp contrast, the national average percentage of used devices of all registered devices (for all states and UTs), is less than half that amount, at almost 27%. The question arises – if more GPs and worksites are using the app, then why is the device use percentage so low? A possible answer lies in the fact that the data counts any GP and worksite that has used the app even once, in the overall count of GPs and worksites that have used the app. Second, the distribution of devices and registration within GPs may be varying greatly, where economically and administratively challenged GPs are not using the app while also accounting for the greater percentage of under-used devices. However, if one were to assume that more well-governed GPs are the ones that have had the most registration, then these are also, alarmingly enough, the very GPs that are driving the least amount of usage. This is happening, even as the GP and worksite is being counted as one that has used the app, as a single occurrence of use is counted in the data. This clearly indicates that the app, even when registered for usage, is unable to be used for issues of connectivity, device compatibility and the individual’s difficulties with the app.

The above can now be discussed in the context of days with both photos. The app is considered to be used properly and attendance is considered marked only if both photos are taken. From our discussion in previous sections, we have also seen how the second half of the day is more prone to glitches, or missed photos due to workers being absent. Thus, keeping in mind proper use of the app, a device can be considered or counted as used, only when it has uploaded both photos. Otherwise, it is simply a device that was registered, but not effectively used to track attendance. A justification for this lies in Chart 6, which overlays the state-wise percentage of days when both photos were recorded and the percentage of registered devices used. For many states, the two percentages line up relatively closely. Even the gap between the national averages for both indicators is closer – the national average of days with both photos is at 18% whereas the national average of used devices is less than double that at almost 27%. The gap between the device use percentage and worksite and GP use indicators is much higher, and more than double in both cases.

Source: Calculated and compiled by the author using the R21.6 report for Device Usage and the R21.11 report for NMMS photos breakdown (all India, as of 12th May 2023). This data depicts the use for the top 20 states by population (according to the 2011 census).

5.3. The Case of Andhra Pradesh: The Ideal Case Study State with Systematic Implementation

Another noteworthy state is Andhra Pradesh. According to Chart 6, the percentage of days with photos is the same as the percentage of used devices, indicating that whenever a device has been used, it has been used correctly to upload attendance. What is incredible as well, is that the percentage of days with both photos for Andhra Pradesh is roughly 18%, exactly the same as the national average. Along with this, 92% of eligible GPs have used the app in the state. At the same time, the percentage of worksites using the app is below the national average, at 48%. The state is indicative of having achieved effective utilisation whenever the app has been used, even though the overall usage has not been too high. This is likely to showcase some best practices for other states, as Andhra Pradesh seems to implement and monitor the MGNREGA scheme steadily, keeping in mind state capacity and realistic targets. This is also expressed in the fact that in 2022-2023, Andhra Pradesh had a high average for person days generated which is above the national average, while also employing relatively fewer households compared to the previous two years (Bhattacharjee, 2023).

5.4. The Case of West Bengal: The State with No MGREGA Work and Payments Since 2021

As one may have noticed, West Bengal is at 0% for device and GP usage. For days with both photos, West Bengal, ironically, shows greater days with both photos than single photo days – but the state only has 27 eligible worksites (MIS Report R21.1). The same is the case for worksite use, which is low enough to make the state insignificant in the analysis so far. All of this is due to the fact that West Bengal has not received MGNREGA funds from the Center since December 2021, effectively leaving almost 17 lakh households without wages paid for work done (Shagun, 2023; Anand, 2023). While the Centre has cited reasons of corruption in the state, the Chief Minister has opposed this as a political move, alleging that West Bengal is being denied funds in order to influence the Panchayat Elections in 2023 (ibid). As a result, there has been almost no work provided in the state, even when it has been demanded, in 2022-2023. What is peculiar, is that section 27 of the MGNREGA act has been used to deny funds to the state, which dates from a time in which funds were released before work was done (Government of India, Ministry of Rural Development 2012). However, this is not the case any longer, and MGNREGA funds are now released after the work has been completed. Thus, if no funds were released in a situation in which work has not been allocated , the households would have been free to pursue more non-MGNREGA work. In contrast, for West Bengal, arises the situation where workers completed the work and yet have since had their wages withheld indefinitely. This is of extreme concern especially since West Bengal accounts for about 10% of working households and 11% of active workers in the country (Shagun, 2023). To put it in context of the discussion so far, the NMMS app has been mandated and its performance is being tracked without the experience of the 4th most populous state in India (according to the 2022 census).

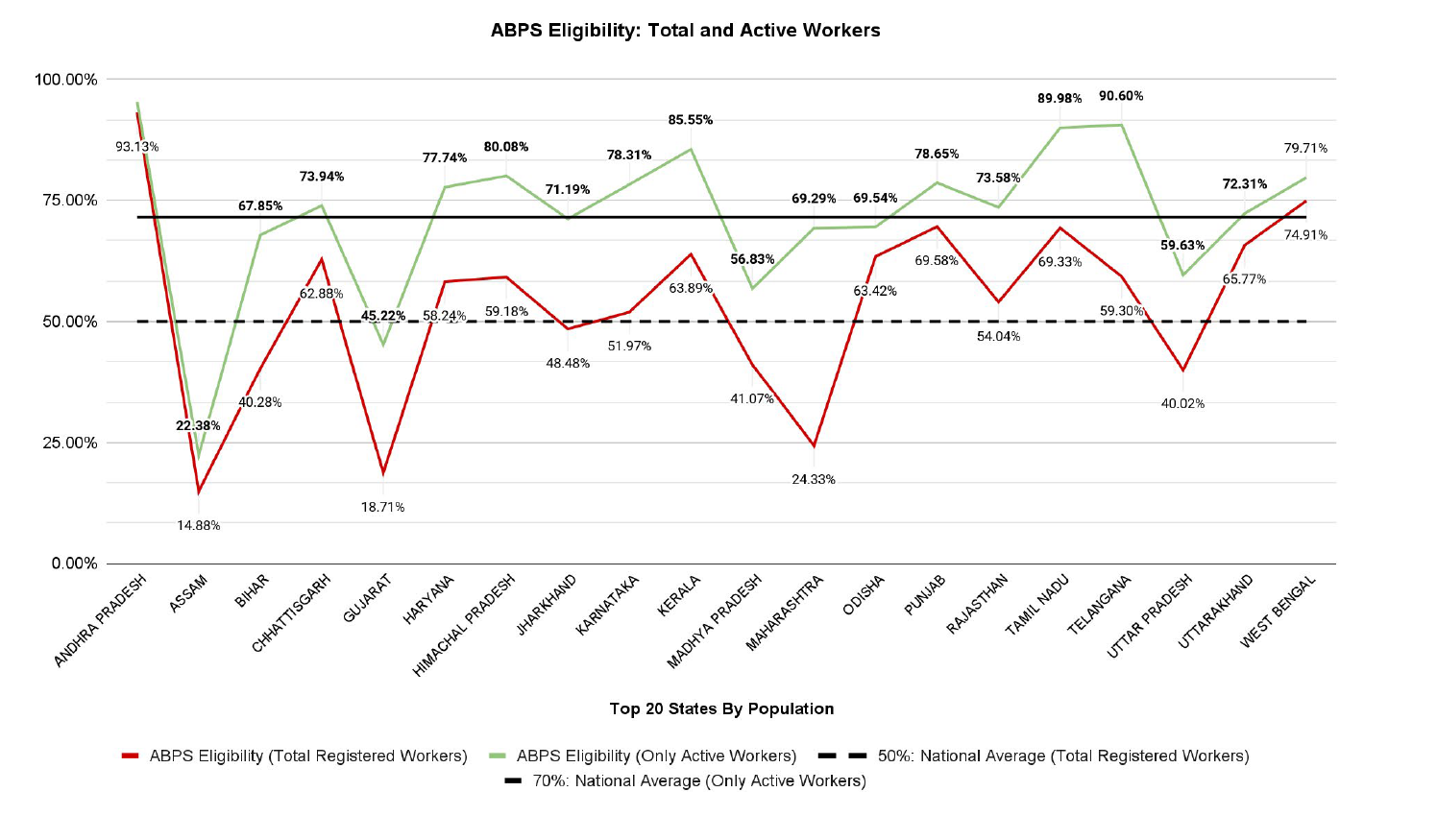

6. Doubling the Digital Burden: Low and Stagnant Eligibility, Missing Data and Issues with the Aadhaar Based Payment System

It is not only the NMMS app that the workers are protesting against, and facing difficulties with. The ABPS system has been made mandatory as well, replacing the “mixed” or “flexible” system of payments that has existed so far (Narayanan, 2023). The flexible system had wages being sent either to the beneficiary’s bank account, or their last account linked to their Aadhar card. Under the new system, all wages are to be paid through the ABPS system, which involves having a worker’s bank account and job card linked to their Aadhar card, and the bank must be linked to the National Payments Corporation of India (NPCI) mapper (ibid). While the Government has claimed that the ABPS system is faster, there is no evidence available to prove this (Dreze, 2023). However, some major flaws emerge – issues with the NPCI mapping take longer to resolve and are a multi-agency process, while in the old system, issues with bank accounts could be solved relatively quickly. The process of NPCI mapping is a complex one itself, and has many steps in the process, requiring the availability of multiple documents, while also needing to account for geographic access, and worker and administrative efficiency. Issues have also been raised with regards to incorrect Aadhar linking (ibid), where a person’s Aadhar number was linked to a different bank account. The multi-step process and agency involvement in the ABPS system is expressed through its different layers of worker authorisation, a seeded job card and an authenticated account do not automatically imply eligibility. Thus, we have high rates of seeding, but low eligibility rates, according to government data itself (Dreze, 2023; MIS R1.9 2022-2023). Chart 7 shows the state-wise breakdown of total workers and active workers eligible for the ABPS.

Chart 7: Source: Compiled and Calculated by the Author using the All India MIS R1.1.9 Aadhar Status Report For FY:2022- 2023 (as of 12th April, 2023) from the MGNREGA website, managed by the Ministry of Rural Development. This data depicts the use for the top 20 states by population (according to the 2011 census)

As of the time of this calculation, the national average of total workers eligible for the ABPS stands at 50%, whereas the national average of active workers stands at 70%. Total workers are those who have been issued job cards in 2022-2023, whereas active workers are those who have received work in the year. An important note to consider is that ABPS eligibility does not automatically imply successful use of the ABPS system, which has been contested by a lot of workers, including those protesting against the app. Furthermore, the number of total and active workers in 2022-2023 are ideally supposed to be similar, as can be seen in the case of Andhra Pradesh, Punjab or Odisha. This is because a worker can be issued a job card and be considered registered, but not receive work due to lack of availability, corruption or face attendance issues through NMMS (the day’s work is not counted). Thus, not all non-active workers are inert, there are those that have not received work despite demanding it Poor ABPS eligibility for registered workers may indicate that a section of workers have not been actively reached out to for ABPS authentication.

7. Government Response and Closing Discussion

The discussion so far clearly points to the fact that almost no state has successfully been able to use the app to record attendance. Further, the striking variation between state capacities is indicative of different challenges and capacities among the state’s MGNREGA seeking workforce and the relevant administrative structure that is entrusted with carrying out the scheme efficiently. The hasty nature with which the app was made mandatory for the entire country, speaks of a policy attitude that prioritises technological upgrade while lacking the spirit of federalism and workers comfort. Although the app aspires to stop corruption, and has been in operation for almost two years, there remains very little clarity on how exactly the app is supposed to achieve that (Narayanan, 2023). Even now, there is no mechanism for matching the worker’s identity with the worker’s picture in the backend of the app, thus resulting in no effective way to address fake job cards and profiles (ibid.). The app, by design, fails to address the very corruption it sought to target. Even if one were to assume the app is able to address corruption, why then, has West Bengal not been allowed to undergo work and receive funds? The rationale behind withholding funds to Bengal was administrative corruption and misappropriation of funds. That is well and good, and if that were the case, the true litmus test of the app would then be perfectly demonstrated if West Bengal were allowed to carry out work. Given that the app is designed to structurally address corruption, the unwillingness of the MoRD to use it to address corruption in a state penalised for corruption is confusing and stands to question the true intention of the ban on work and funds for the state. It remains to be seen whether the funds would be suddenly released and work be allowed once the West Bengal Panchayat Elections have taken place in May 2023. Of course, whether that would be an informed policy decision, a coincidence, or a consequence of the election outcome bears room for discussion, albeit not in this paper.

In February 2023, in a response to the news website IndiaSpend, the MoRD said “as such no major issue has been reported in its implementation”, when asked about the NMMS initiative (Pailiath & Dutta, 2023). This response is difficult to accept, or even interpret, as it comes against the backdrop of ongoing and sustained protests at New Delhi (ibid). Further, the issues of implementation are not ambiguous, as the MoRD’s own data suggests. In the year preceding the announcement that made the app mandatory, nearly 45% of eligible worksites had either never used it, or stopped using it completely (discussed in previous sections).

However, as of May, the MoRD was forced to respond. Responding to the concern of workers not being able to tell if their attendance was recorded, the MoRD is now considering sending a text message regarding the worker’s attendance to the worker at the end of each work day (Nair, 2023c). The rationale for this too, is questionable. A text message regarding the worker’s attendance solves the issue of knowing one’s attendance, only if the attendance was recorded correctly in the first place. However, it does nothing to solve the issue of incorrect attendance to begin with, or the matching of worker’s details to their pictures, or the need to remain at the worksite for both periods of the day. What is further peculiar, is why the MoRD considers a technology based notification system to be a solution for a workforce that is facing technological challenges at the root of implementation itself. A text message retains the same issues of connectivity, device availability, app glitches and incorrectly entered attendance. This is effectively a suggestion of a technological band-aid for a gaping wound that is the NMMS initiative.

Finally, there remain the issue of the NMMS glitches: all applications introduced by the government are to go through Standardisation Testing and Quality Certification (STQC), its sole purpose being to ensure testing and quality certification (Gaur, 2023). There is no information on whether the NMMS app went through the STQC process, and neither is the source code of the app available in the public domain for independent analysis and testing. Srinivas Kodali, a researcher with the ‘Open Source Software Movement’ said that the NMMS app is “the perfect example of privacy for government and transparency for citizens” (ibid).

There also remains the double burden of the ABPS system. The response of the MoRD to the protests has been to extend the deadline for bringing more workers under the ABPS cover, to 30th June (Nair, 2023d). Once again, while the centre has taken heed of the worker’s difficulties, it has failed to address the core concern regarding the ABPS system – the time taken to solve problems is greater than in the old account based system, there is no clarity regarding how it makes the system more efficient and it is not faster than the account-based system either (Dreze, 2023). For some years now, workers have been trying to draw attention to missed payments from the past, while also highlighting the persistent issues of delayed payments, none of which are accurately solved by the ABPS system (ibid).

Between the NMMS app and mandatory ABPS, two broad policy attitudes have emerged; one, the present Government places a considerable degree of importance on digitisation to be the most disruptive way for the future of social security policy making, and two; the effective burden of implementing any future and present digitisation falls on the individual. In the case of MGNREGA, the worker is expected to incorporate the needs of the app by being present at two different reporting periods, trading off their own potential non-MGNREGA work time. The MGNREGA mate is expected to own, operate, and maintain the device needed to update attendance. The government has also established an ultimatum-based approach to such initiatives – it is the burden of the workforce to follow and incorporate the changes, regardless of widespread difficulties, and the alternative for non-compliance or inability is to be excluded from the welfare and benefits entirely. Arguably, the role of technology in social protection should expand such measures to incorporate greater flexibility and opt-in access; the current digital orientation, unfortunately, is more restrictive than the methods that preceded it. The experience of digital infrastructure is also gendered, as women have lesser access to personal phones than men (Scroll Staff, 2022). The gender gap in digital awareness must be accounted for, in order to prevent structural issues that cause more women to disengage from social protection schemes and general developmental provisions.

A major fall out of ultimatum based digitisation is not in the glitch and missing results itself, but is one that strikes negatively into the sense of trust that the semi-skilled and unskilled Indian workforce places in governance, technology, and social sector schemes. A major aspect of administrative ease and policy implementation is the trust of the stakeholder communities in due process of policy (Dahn, 2022). This goes beyond simple provision or existence of policy, but necessarily includes communication of policy, ease of use, training of stakeholders, and most crucially – redressal of grievances. The current MGNREGA framework fails on every front, except provision. This is of significant concern, for the following reasons – first, the wages of this group go unpaid as their attendance is effectively nill, second, as this group has for a year been unable to use the app, it is likely to result in this group not demanding work at all, even when they need it. The latter is of concern on many levels; the depression of expressed demand in MGNREGA due to a technological barrier is not indicative of the true demand and need of MGNREGA work. In 2023, immediately after the announcement to make the app mandatory, the number of person-days generated fell sharply, and below the number for the same period in 2022 (PTI, 2023). This fall has been attributed to the NMMS app, which in a span of two months, resulted in less effective demand for work, fewer person-days, and more cases of work done without attendance marked.

The example of MGNREGA speaks strongly to the nature of governing through ultimatums. In the year preceding the decision to make the app mandatory, nearly 45% of the eligible worksites had stopped using or interacting with the app, and only the experience of 56% of worksites that continued using the app was deemed enough to make it mandatory. Among the 55-56% of worksites that have used the app, consistent challenges have been reported. One may argue that the government considered that making the app mandatory would be the only way to get states to use it. If that were the case, it still remains worrying that in a federal democracy, deliberation was not the way to upgrade one of the world’s largest social protection schemes. But even if one were to discard any conceptual discussion of political participation, federalism and workers’ rights, at the very least, even when the app has been used, it has failed. The mandation of the app has been done in the backdrop of both insufficient coverage and technical failure, a trend that speaks poorly of the commitment towards social security of the most in need. Finally, the budget for the scheme has been slashed by 33% from the previous year, a move that has been criticised as being intentionally undertaken to phase down demand for workers.

Among all of this, the question that emerges then, is what does the Indian state envision for the future of social security schemes in general, and more specifically, MGNREGA? There is nothing wrong with technological upgrade on its own, provided that the technology creates a system of transparency for everyone involved, expands the comfort and ease of access and does not exclude those that are in need of the welfare the most. The current situation can be meaningfully addressed quite simply by getting the NMMS app certified and tested, while making its source code available for independent research and scrutiny. There is a case to be made for app-based attendance itself, on principle, being ineffective, as most of the MGNREGA payments are decided using the work done by the worker at the end of the day. Even if the NMMS app needs to be used, all the glitches need to be tested and solved for. Additionally, such a system is reliant on the prevalence of individual phone ownership, which shifts the burden to the worker. A much better understanding of digital literacy and phone usage is needed before digital processes are introduced. As discussed before, the case of sending text messages retains the same problems as the NMMS app.

Digital governance, when conducted through ultimatums, is likely to result in digital resistance. The experience of MGNREGA and NMMS shows the potential for workers to lose trust in technological advances beyond the more consumer-driven, leisurely aspect of technology. Inefficient digital governance then benefits only the administration, and any players that may stand to benefit from the collection of data. Concerns thus remain on who the recent trend of digitisation has been for, as the workers’ benefit continues to be shadowed by a process that prides itself on technological advance for the sake of technology.