Background

For the large populace of Delhi, the Yamuna holds many meanings. It has historically been considered a prime water source for the city, and has now become the most polluted river stretch. It also divides the city in two halves. The 22km length of Yamnuna River passing through the capital city presents a small 2 per cent of the total river length, but accounts for nearly 76 per cent of the total pollution of the river (Singhal, 2023). The floodplains of the river are also an important part of the ecosystem, and unregulated regions of construction within the city have increasingly become a concern. Floodplains are essentially the buffer areas, as the name suggests, which retain water in case of heavy rainfall that poses the threat of urban floods, which have risen in recent years as witnessed in July of 2023 (SANDRP, 2024).

These risks are exacerbated by the encroachment of the Yamuna floodplains. The extent of this encroachment paints a worrying picture; according to recent reports, nearly 75% of Delhi’s Yamuna floodplains have been encroached upon, which is more than 7,361 hectares out of the total 9,700 hectares (ET Online, 2024). However, many news reports point out that the physical demarcation of the floodplains is still incomplete, despite the Delhi government’s claim that it has been completed (NGT,2023; Gandhiok, 2025). This major lag can delay the process of helping to identify and protect the ecosystem from encroachment despite the push from the National Green Tribunal (NGT) for nearly a decade (Babu, 2024).

The NGT first took notice of the encroachment of the Yamuna and issued guidelines to the Delhi Development Authority in 2015, regarding matters from 2012 and 2013 on the rampant construction on the floodplain (NGT,2024).

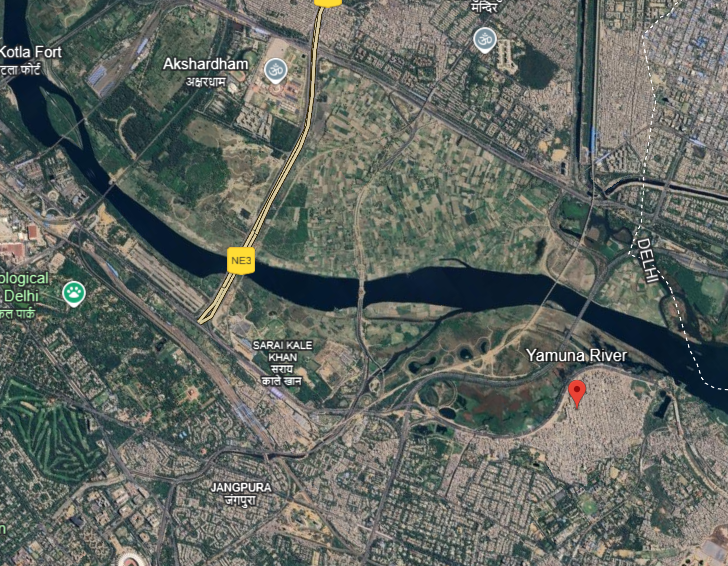

The order noted several expansions of construction, including Sur Ghat in northern Delhi, Baansera, and Millennium Bus Depot near Sarai Kale Khan which were authorised by the DDA and are built upon floodplains that it had previously claimed to have cleared (NGT,2024) and thereby directed the Central Pollution Control Board to file a report of the violation by the developmental authority. Now the DDA plans to develop multiple projects along the Yamuna riverfront, including an Amrut Biodiversity Park, a Nature Park, an eco tourism area, and a ghat area (DDA, n.d.). However, the issue of the Yamuna floodplains isn’t simply a directive not followed; instead, it pivots to a complex issue highlighting unhindered encroachment, environmental and safety concerns, developmental aspirations, rehabilitation questions, and the story of a busy capital.

A history of encroachment and environmental risks

The encroachment of Yamuna floodplains is not a new occurrence; it can be traced back to the early nineteenth century (Khan &Bajpai, 2014). However, studies of temporal changes in the river can be found from the 1980s, with satellite images allowing a look at spatial variation in the river courses and their corresponding floodplains.

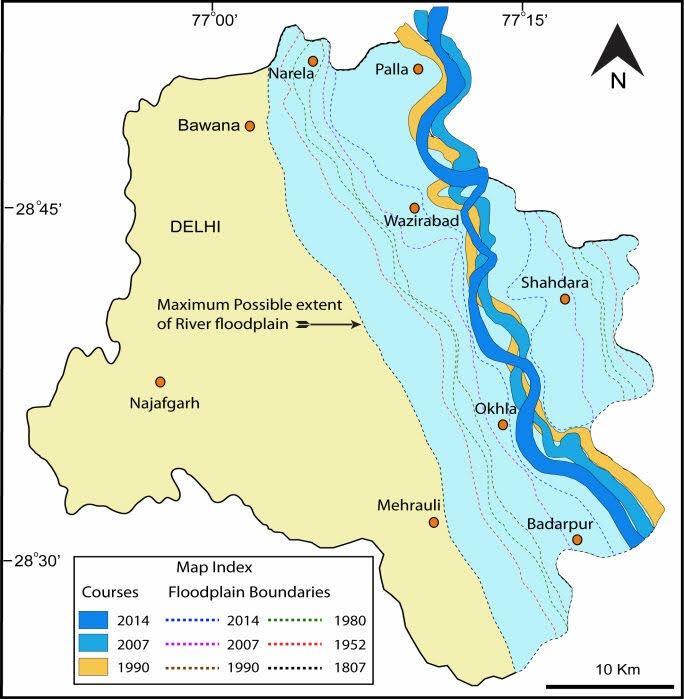

Figure 1- Map of temporal changes in Yamuna river courses for years 1990, 2007, 2014 and associated floodplains visible extent; Khan & Bajpai, 2014).

Figure 1- Map of temporal changes in Yamuna river courses for years 1990, 2007, 2014 and associated floodplains visible extent; Khan & Bajpai, 2014).

Figure 2- Google Earth Images of Yamuna River through Delhi and areas around it, 2025.

Encroachment over the floodplains around 1990, 2007, and 2014 led to the development of settlements such as Okhla, Badarpur, Wazirabad, and Shahdara on the other side of the river (Khan, 2014). The growing urbanization needs have also led to the rapid development of civic structures, roads, bridges, flyovers, playgrounds, and now metro stations on the floodplains (Khan, 2014). Over the last decade, the NGT has issued guidelines and orders to the Delhi Development Authority (DDA) directing them to take action. These actions are based on environmental risks that are posed as a result of anthropogenic activities and flood flows that can rise due to the obstruction caused by this encroachment. Urbanization in the floodplains has also led to several significant hydrological impacts, including amplified runoff, increased maximum drainage, and low-flying floodplains amplify the experiences of flooding due to the lack of natural drainage systems (Anand et al., 2024).

In a status report, the DDA stated that the encroachment drives were being regularly carried out in the Yamuna encroachment, and they have freed 401.4 hectares of land from the floodplains by demolishing illegal structures, including slums, religious structures, dairies, playing fields, and cultivation (Gandhiok, 2024). They also referred to a stay order by the Delhi High Court for some areas around the Majnu Ka Tilla.

However, the assumption that those in the vicinity are the sole polluters of the Yamuna can be severely misleading. Industrial units, many of which significantly contribute to the pollution of the Yamuna, have not been consistently and effectively removed. According to the 2024 report by the Delhi Pollution Control Committee (DPCC), over 2,000 polluting industrial units continue to operate illegally in the Yamuna’s designated industrial zones, despite repeated court orders mandating their relocation (Delhi Pollution Control Committee, 2023).

On the other hand, cultural festivals have also been organized, which has led environmentalists and the NGT to express concerns regarding the damage caused to the Yamuna floodplains (Sen, 2016).

While concerns about ecological degradation of the Yamuna floodplains are valid and urgent, they cannot be viewed in isolation from the socio-economic realities of those who inhabit these spaces. A considerable proportion of the “encroachers” are slum dwellers, who have also faced the first line of action from the removal of encroachment in areas by the DDA. These communities have historically been pushed to the peripheries of the city due to systemic exclusion and a lack of affordable housing through the years (Bhan, 2009). The assessment of environmental risks must also take into consideration the questions of social justice, some of which were also asked during the development of the Sabarmati River Front.

Encroachments and Rehabilitation: Questions of Access

At the peak of COVID-19, the DDA led a demolition drive in Batla House, affecting nearly 800 families mainly consisting of daily wage and domestic workers (Patil, 2021). The demolition drive and clean-up of the Yamuna floodplains have restarted with greater rigour, with the slum clusters in areas like Shastri Park, Okhla, and Kashmere Gate receiving notices of eviction in early 2025 (Ashraf, 2025). While many of these clusters have indeed developed over decades over what is designated as ecologically sensitive land, it is important to recognize that they have emerged as an outcome of social and economic pressures that have been fueled by long-standing political promises of regularisation, which have remained unfulfilled. The current eviction-centric approach without the promise of compensation or rehabilitation raises alarm. The Delhi High Court has also declined the immediate relief to the slum dwellers who fear demolition action in Okhla for being declared “rank trespassers” on the Yamuna floodplain (Garg, 2025).

This is not the first time that the urban poor have borne the price of ecological conservation and development plans. The Sabarmati River Front Development project, which was started in 2006, saw the forced displacement of over 1000 families, many of whom have also suffered from loss of livelihoods (Patil, 2018). Unlike the case in Delhi, those impacted by the Sabarmati project were promised rehabilitation but remain waiting many years later, while the project has entered its next phase of development and expansion (Patil, 2018). This raises some fundamental questions on whether environmental conservation lies solely at the feet of the urban poor. Moreover, the floodplains are also home to thousands of farmers whose land and livelihood will be directly impacted by the removal or encroachment.

In 2019, the NGT banned all farming activity on the Yamuna floodplains following a study that found high levels of lead in vegetables and corresponding soil samples by the National Environmental Engineering Research Institute (NEERI) (Konai, 2022). Environmentalists are increasingly suggesting that farming does not threaten the region’s ecology, especially with the controlled use of fertilisers and pesticides (Shukla, 2024). In regions such as the Carson Valley in Nevada, U.S, floodplain agriculture is being used as a protective mechanism to retain the lands for many decades (Coborun & Lewis, 2011). The Regional Floodplain Management Plan of the Carson Valley recommends that communities like Carson Valley should “protect the natural functions and benefits of the floodplain lands,” and agriculture sustains much less damage from urban or residential development (Coborun & Lewis, 2011).

Redeveloping floodplains through ecological agriculture offers a more sustainable, inclusive and adaptive approach compared to constructing like those seen in Delhi’s Asita East project. While the Asita East initiative aimed to restore the Yamuna floodplain by planting native vegetation and creating green spaces, it has faced criticism for incorporating concrete pathways and other permanent structures (Semalty, 2024).

Development of Yamuna Riverfront

The central government, under the Jal Shakti Ministry, has stepped into the redevelopment of the Yamuna and prepared the ‘Yamuna Master Plan’ to prioritize the rejuvenation and cleaning of the river (Mishra, 2025).

The DDA has also started the execution of the large-scale project to develop the Yamuna Riverfront with the makeover of 370 acres of floodplains. The plan proposes to use the land for recreational activities, including biodiversity parks and other commercial activities, including eco-tourism. The development of the Yamuna Riverfront is modeled on the Sabarmati Riverfront (ET Online, 2025). The DDA has floated a request for proposals (RFP) to prepare a feasibility report and select a developer for the riverfront project; the project is to be developed in a public-private partnership (PPP) mode (Sinha, 2024). The park is set to generate employment during construction and revenue for the government through the planned recreational activities; however, the revenue model of the park cannot be confirmed at this point.

Yet, like the Sabarmati Riverfront, the park could also employ a self-financing revenue model by developing attractions to boost tourism, stimulating local businesses (Arterial Magazine, 2024).

The lieutenant governor of Delhi, however, suggested that the riverfront development of Yamuna will not be similar to the Sabarmati riverfront project because of the unique features of Delhi as a capital (TOI, 2025). He states that only certain patches of the river flow in Delhi can also be developed, and that they aim to introduce green spaces and flower fields. Furthermore, there are considerations to use the river for the transport of goods, especially around the Najafgraph drain (TOI, 2025).

The Yamuna Riverfront project is launched with ecological objectives, such as restoring natural habitats, but its focus has also been on economic benefits. Through strategic planning, the project aims to transform the Yamuna into a vibrant urban space; however, whether it genuinely delivers on the promises of environmental sustainability and inclusive growth remains a critical concern. The Gomti Riverfront in Lucknow, another riverfront development project initiated by the U.P. government, has led to changed hydraulic regimes, which has led to the loss of river processes and ecosystems (Dutta et al., 2018).

Conclusion

Rivers have always been lifelines of civilisations, now lost to pollution. Many communities flourish from livelihoods that surround the river ecosystems. Yet, the Yamuna, once sacred and central to Delhi’s cultural landscape for many communities, now stands as a symbol of urban neglect.

The Yamuna Riverfront project is a bold attempt to rewrite the narrative, drawing inspiration from other models in the country, but these models also present lessons to avoid the same gaps in addressing social injustices while focusing on environmental restoration. At its core, the project seeks to breathe life back into the river, to reclaim its banks as spaces of ecological richness and social vibrancy. However, as the city reimagines the Yamuna’s future, balancing ambition with responsibility is the critical challenge. In addressing some of the key environmental risks that emerge from the encroachment of floodplains, the NGT has pushed for major demolition drives spearheaded by the DDA; yet, these drives target much of the population that has no other place in the city. The move also disproportionately affects the farmers without sufficient scientific proof that agriculture on floodplains must be seen as detrimental to the river ecosystem. While the revival of the Yamuna is pertinent to ensuring a secure future for the capital city, the path to it must also ensure security to these sections of society. To ensure lasting impact, the Yamuna’s revival must be more than a beautification drive and must not come at the cost of loss of lives, homes, and community for many.

Unfortunately, the riverfront projects across the country have shown a disturbing pattern of displacement and little relief to a class of citizens already faced with injustice and livelihood challenges. The idea of beautification on the debris of destroyed homes seems nugatory. This presents an opportunity for Delhi and the Yamuna Riverfront to become a model of participatory urbanism—one that integrates environmental justice, safeguards livelihoods, and fosters a deeper public connection with nature. The riverfront should be a shared space—not just for leisure, but for learning, healing, and belonging.