Introduction

Throughout India’s history, both pre- and post-independence, Maharashtra and West Bengal have been leaders in advancing social reforms for women. Maharashtra’s contributions include the pioneering efforts of Jyotiba Phule and his wife Savitribai Phule, who broke societal barriers by establishing the first school for girls in Pune. Reformers like Dhondo Keshav Karve further pushed boundaries by advocating for widow remarriage, women’s education, and legal rights.

In West Bengal, reformers like Raja Ram Mohan Roy emphasized education as the cornerstone of gender equality, actively campaigning against oppressive practices like sati. Women in West Bengal, inspired by these movements, began to mobilize themselves. As Singha (2021) highlights, well-educated women in the region played an active role in creating grassroots movements to uplift their peers, setting a precedent for feminist activism in India.

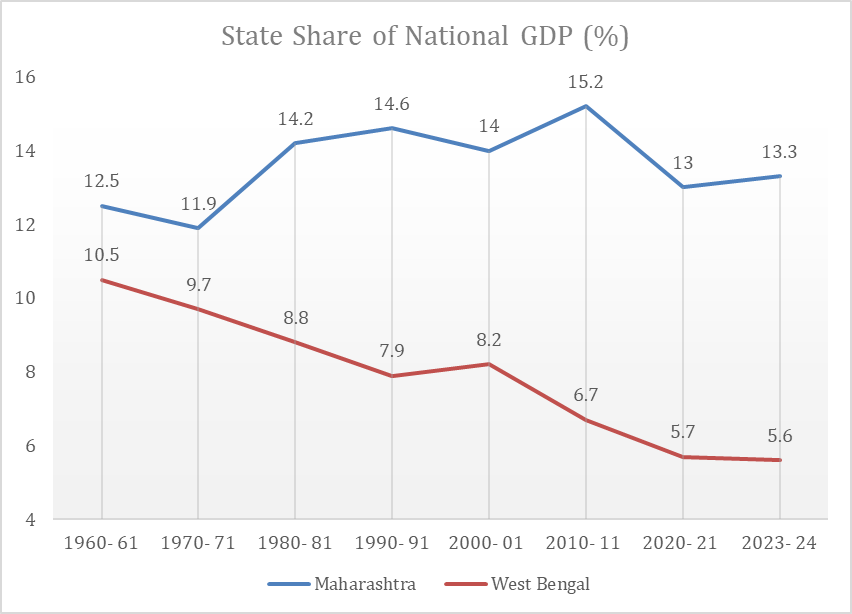

Post-independence, Maharashtra and West Bengal began from relatively comparable positions in terms of socio-economic development and reformist foundations. Both states had strong social movements advocating for women’s empowerment and health, alongside economic similarities. In 1950–1951, 33% of India’s total industrial production came from Bombay (which included Gujarat) and 27% came from West Bengal (Roy, 2011). However, their trajectories diverged decades down the line, as reflected in key indicators like state GDPs and social metrics.

As the chart highlights, Maharashtra consistently maintained higher GDP figures compared to West Bengal. For instance, in 1960–61, Maharashtra’s share of the national GDP was 12.5%, slightly ahead of West Bengal’s 10.5%. The gap widened by 2023–24, with Maharashtra at 13.3% and West Bengal lagging much behind at 5.6%. West Bengal’s share in the national GDP has only reduced over the years.

Source 1: Working Paper by PM-EAC

Source 1: Working Paper by PM-EAC

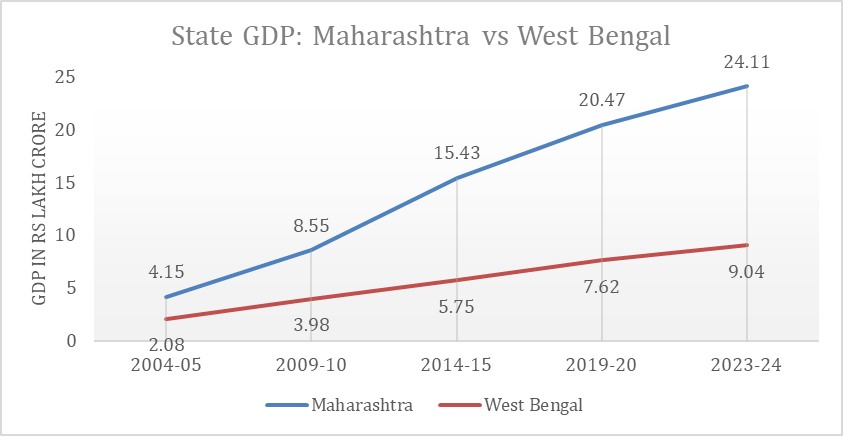

The condition is no different when it comes to both the states’ actual GDP over the past two decades. Maharashtra’s GDP grew significantly, from ₹4.15 lakh crore in 2004–05 to ₹24.11 lakh crore in 2023–24, reflecting robust industrialization and service sector growth. In contrast, West Bengal’s GDP increased from ₹2.08 lakh crore to ₹9.04 lakh crore over the same period, showing slower economic growth.

Source 2: NITI Aayog

Source 2: NITI Aayog

This disparity indicates Maharashtra’s stronger economic performance and resource base, likely allowing for higher allocations toward women’s healthcare initiatives compared to West Bengal. This comparison raises questions about how economic growth translates into policy outcomes for women’s welfare and warrants a comparative study to examine whether Maharashtra’s economic growth has translated into better women’s healthcare schemes and budget allocations compared to West Bengal’s relatively slower economic progress.

Women’s health significantly influences economic performance, as healthier women contribute to increased workforce participation, enhanced productivity, and improved socio-economic outcomes. A McKinsey Global Institute (2015) report estimates that advancing women’s equality could add $12 trillion to global GDP by 2025. However, health challenges, such as anemia, impede women’s economic engagement. Anemia affects 54.2% of women in Maharashtra and 71.4% in West Bengal, leading to reduced physical capacity and productivity. Investing in women’s health yields substantial economic returns; for instance, closing the women’s health gap could unlock a $1 trillion GDP opportunity annually by 2040 (Perez et al., 2024). Therefore, targeted healthcare investments are essential to fully harness women’s potential as drivers of economic growth. The critical linkage between women’s health and economic performance provides a rationale for analyzing healthcare investments and policies in Maharashtra and West Bengal to evaluate their alignment with broader economic objectives.

Budget Allocation Trends

Budget allocation for healthcare, particularly women’s healthcare, is a critical indicator to assess the government’s priority to address gender-specific health challenges. The National Health Policy 2017 emphasised the need for increased public health investment. The policy proposed that health expenditure as a percentage of GDP should rise from 1.15% to 2.5% by 2025. The policy also urged the states to allocate over 8% of their budgets to healthcare by 2020.

Now, four years past this milestone and in the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic, it is crucial to evaluate the extent to which these goals have been realized. The pandemic highlighted vulnerabilities in healthcare systems, emphasising the need for stronger investments in both infrastructure and targeted programs like maternal and reproductive health (Goyal et al, 2020). Examining whether both central and state governments, specifically Maharashtra and West Bengal, have met the targets set by National Health Policy will provide insights into their prioritisation of women’s healthcare amidst competing fiscal demands.

| Health Expenditure by Central and State Govts Combined | |||||||||

| Year | 2015-16 | 2016-17 | 2017-18 | 2018-19 | 2019-20 | 2020-21 | 2021-22 | 2022-23 (RE) | 2023-24 (BE) |

| Expenditure in Rs Crore | 1,75,272 | 2,13,119 | 2,43,388 | 2,65,813 | 2,72,648 | 3,17,687 | 4,56,109 | 5,12,742 | 5,85,706 |

| Percent of GDP | 1.3 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 1.4 | 1.6 | 1.9 | 1.9 | 1.9 |

Source 3: Economic Survey of India 2022-23 and 2023-24

The data from the table highlights that India’s healthcare expenditure as a percentage of GDP has seen a gradual but insufficient increase from 1.3% in 2015-16 to 1.9% in 2023-24. Despite a significant rise in absolute expenditure—from ₹1.75 lakh crore in 2015-16 to ₹5.85 lakh crore in 2023-24. While the expenditure has increased by 234% from 2015-16 to 2023-24, the proportion of GDP allocated to health has not met the target of 2.5% of GDP by 2025. With only one year left to achieve this ambitious goal, the current allocation indicates a persistent shortfall in prioritizing healthcare, even as the COVID-19 pandemic underscored the need for robust public health infrastructure.

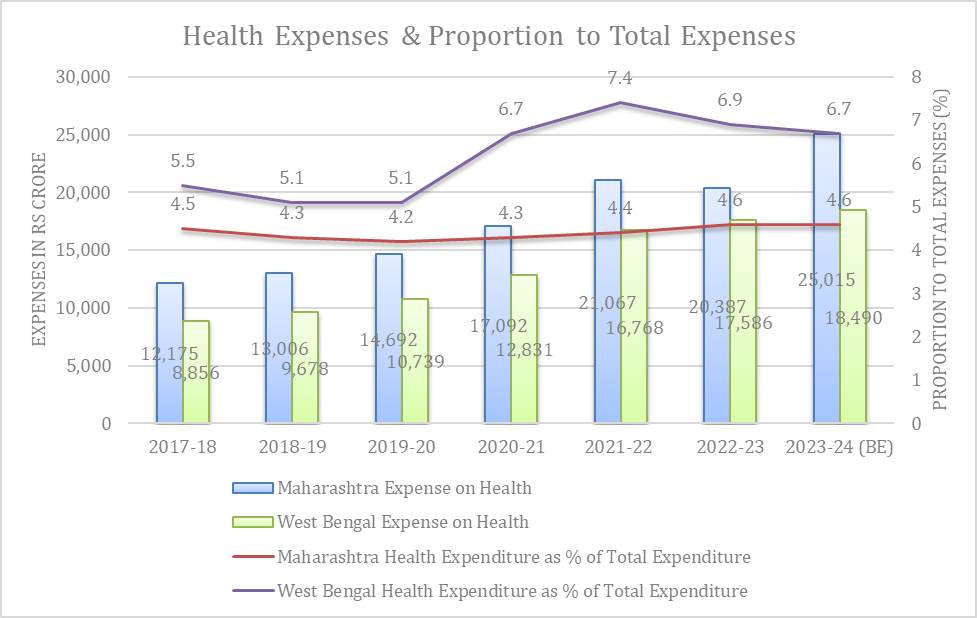

Source 4: Reserve Bank of India: State Finance—A Study of Budgets

The chart compares health expenditure and its proportion to total expenditure for Maharashtra and West Bengal from 2017-18 to the Budget Estimates (BE) for 2023-24. In terms of absolute health expenditure, Maharashtra shows a steady upward trend, increasing from ₹12,175 crore in 2017-18 to ₹25,015 crore in 2023-24 (BE). The sharpest increase occurred during the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020-21, when health spending rose from ₹14,692 crore in 2019-20 to ₹17,092 crore. This increase of approximately ₹2,400 crore reflects Maharashtra’s response to the public health crisis. Post-pandemic, Maharashtra maintained higher health spending levels, reaching ₹21,067 crore in 2021-22 and ₹20,387 crore in 2022-23. The Budget Estimates for 2023-24 project further growth to ₹25,015 crore, demonstrating a consistent increase in healthcare expenditure.

West Bengal, in comparison, spends less on health in absolute terms but has also shown a gradual increase in expenditure, rising from ₹8,856 crore in 2017-18 to ₹18,490 crore in 2023-24 (BE). Similar to Maharashtra, West Bengal’s health spending saw a significant rise during the pandemic, increasing from ₹10,739 crore in 2019-20 to ₹12,831 crore in 2020-21, an increase of approximately ₹2,100 crore. Although the state’s expenditure on health remains significantly lower than Maharashtra’s, it highlights efforts to expand spending within its fiscal capacity.

When analysing health expenditure as a proportion of total state expenditure, Maharashtra’s share has remained relatively stagnant—to around 4.5% over the years. While Maharashtra’s absolute spending has increased, its prioritization of health in the overall budget has seen only marginal improvements. Despite its larger fiscal capacity, the state’s health expenditure as a percentage of total spending remains modest. In 2023, Maharashtra was at the bottom of all states when it comes to health budget in proportion to the overall state budget (Iyer 2023). In contrast, West Bengal has consistently allocated a higher proportion of its total expenditure to health compared to Maharashtra. In 2017-18, health expenditure accounted for 5.5% of West Bengal’s total spending. The share rose significantly during the pandemic, peaking at 7.4% in 2021-22. This increase underscores West Bengal’s prioritization of healthcare during the COVID-19 crisis. While West Bengal is steadily approaching the National Health Policy’s target of allocating 8% of its budget to healthcare, Maharashtra must make a concerted effort to significantly increase its allocations to meet this benchmark.

While discussing the expenses, it is important to analyse how much was allocated to healthcare over the years, and how much of the allocated budget was spent on healthcare in both the states.

|

Health Budget vs Actuals |

||||||

| Year | Maharashtra | West Bengal | ||||

| Actuals | Budget Estimate (BE) | % of Actuals to BE | Actuals | Budget Estimate (BE) | % of Actuals to BE | |

| 2017-18 | 12,175 | 10,757 | 113 | 8,856 | 7,596 | 117 |

| 2018-19 | 13,006 | 13,450 | 97 | 9,678 | 8,964 | 108 |

| 2019-20 | 14,692 | 15,919 | 92 | 10739 | 9,727 | 110 |

| 2020-21 | 17,092 | 17,288 | 99 | 12,831 | 11,280 | 114 |

| 2021-22 | 21,067 | 19,060 | 111 | 16,768 | 16,576 | 101 |

| 2022-23 | 20,387 | 22,536 | 90 | 16,858 | 17,786 | 95 |

| 2023-24 | 25,015 | 18,490 | ||||

Source: Budget Documents of Maharashtra and West Bengal

The data indicates budget utilization for health expenditures in Maharashtra and West Bengal. It is pertinent to note that while Maharashtra did not fully utilise its allocated budget even during the peak years of COVID i.e. FY 2019-20 and 2020-21, it did catch up and utilise more than allocated funds in the FY 2021-22. It needs to be assessed if this fluctuation in expenditure can also be attributed to the political instability in Maharashtra post the 2019 assembly election in the state.

On the contrary, West Bengal has been consistent with its utilization with actual spending consistently exceeding estimates until 2021-22, reaching 117% in 2017-18 and 114% in 2020-21, reflecting a focused response to healthcare needs, particularly during the pandemic. However, in 2022-23, West Bengal’s actual spending fell to 95% of the BE, showing a slight decline. Overall, while West Bengal has managed better alignment between allocations and spending, Maharashtra needs to improve its fund utilization to address healthcare priorities effectively.

Per Capita Spending

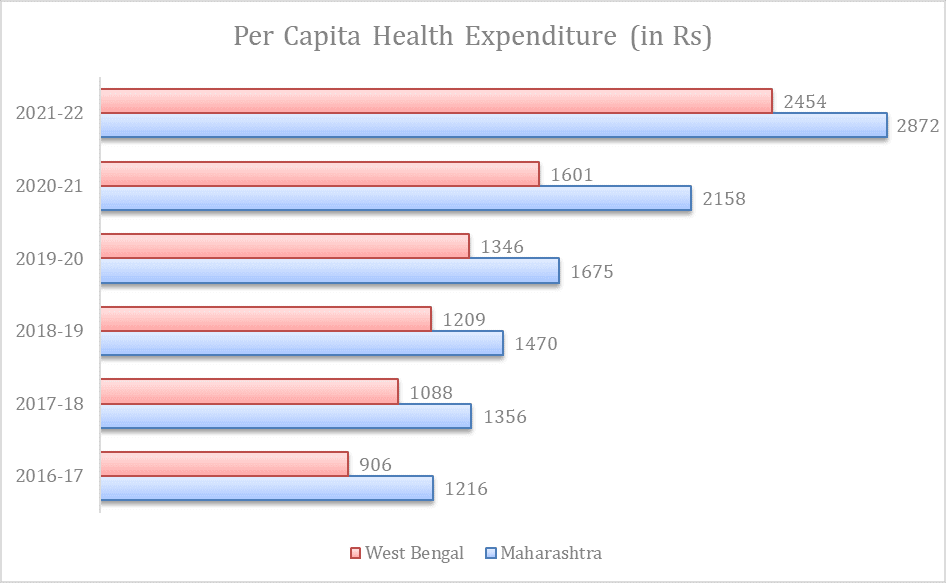

While the budget allocation for healthcare is increasing over the years, it is also important to see if there is growth in per capita spending on healthcare. As for the national data, government health expenditure per capita tripled from ₹1,108 in 2014-15 to ₹3,169 in 2021-22 (National Health Accounts, 2024). This is an 82% increase in per capita spending. India’s out-of-pocket expenditure as a share of total health expenditure has decreased from 64.2% in 2013-14 to 39.4% in 2021-22, marking a positive trend according to the National Health Accounts Estimates.

The data on per capita health expenditure for Maharashtra and West Bengal from 2016-17 to 2021-22 reveals a steady increase in spending for both states, reflecting a growing emphasis on healthcare investments. Maharashtra consistently recorded higher per capita expenditure compared to West Bengal, starting at ₹1,216 in 2016-17 and reaching ₹2,872 in 2021-22. West Bengal’s figures rose from ₹906 to ₹2,454 during the same period.

A sharp rise in health expenditure during 2020-21 for both states is indicative of increased healthcare needs during the COVID-19 pandemic. Maharashtra, one of the worst-affected states, saw its per capita health spending jump by ₹483 (28.8%) from the previous year, while West Bengal’s spending increased by ₹255 (18.9%) during the same period.

Source 5: National Health Accounts Report, MoHFW

Source 5: National Health Accounts Report, MoHFW

Gender Budget for Women’s Healthcare

Maharashtra introduced Gender and Child Budget in the year 2020-21, whereas West Bengal introduced it recently—in budget 2024-25.

The Gender Budget Healthcare Data for West Bengal and Maharashtra highlights significant differences in gender-focused healthcare allocations. West Bengal consistently allocates a substantial portion of its health budget to schemes targeting women. In 2022-23, for instance, ₹8,141.87 crore was spent on women-specific and women-majority schemes, with projections for 2024-25 reaching ₹9,786.27 crore. Notably, West Bengal shows a clear prioritization of schemes benefitting women, with a significant portion categorized under 30%-99% women-specific schemes, which accounted for over ₹7,500 crore in 2022-23.

| Gender Budget for Healthcare (In Rs Crore) | ||||||||

| 2018-19 Actuals | 2019-20 Actuals |

2020-21 Actuals |

2021-22 Actuals |

2022-23 Actuals |

2023-24 RE |

2024-25 BE |

||

| West Bengal | 100% women specific schemes | No gender budget | 620.36 | 484.67 | 319.29 | |||

| Less than 100% women specific schemes | 7,521.51 | 8,548.91 | 9,466.98 | |||||

| Total | 8,141.87 | 9,033.58 | 9,786.27 | |||||

| Maharashtra | 100% women specific schemes | 55.61 | 120.84 | 87.53 | 96.03 | 73.66 | 78.38 | 74.25 |

| Less than 100% women specific schemes | 328.47 | 462.78 | 255.20 | 78.64 | 509.04 | 1,022.42 | 1,126.49 | |

| District Plan | 9.66 | 17.84 | 22.47 | 28.26 | 18.46 | 1.00 | 0.00 | |

| Total | 393.74 | 601.46 | 365.19 | 202.93 | 601.15 | 1,101.80 | 1,200.74 | |

Source 6: Gender Budget Documents of MH and WB

In contrast, Maharashtra’s gender-focused healthcare spending is significantly lower. In 2022-23, the state spent ₹601.15 crore on women-specific and women-majority schemes, with projections for 2024-25 at ₹1,200.74 crore. While there is a visible increase in allocations over the years, the figures remain significantly below those of West Bengal—which has lesser budget allocation for healthcare in absolute numbers. Maharashtra also demonstrates a skew towards 30%-99% women-specific schemes, with minimal expenditure on 100% women-focused schemes (e.g., ₹73.66 crore in 2022-23), which suggest that Maharashtra needs to scale up its efforts in incorporating gender-responsive budgeting in healthcare. Such investments are critical for improving women’s health outcomes, addressing systemic inequalities, and achieving broader goals of gender equity in public health.

However, it is pertinent to note that factor contributing to the disparity in gender-budgeted healthcare expenditures between West Bengal and Maharashtra, in addition to Maharashtra’s lack of adequate allocation, could be the differing methodologies employed in their gender budget allocations. West Bengal’s healthcare gender budget appears to account for both administrative expenditures and direct scheme expenditures, thereby presenting a more comprehensive view of overall spending. In contrast, Maharashtra seems to focus exclusively on direct expenditures related to healthcare schemes, omitting administrative costs from its calculations. Such differences underscore the need for a standardized framework for gender budgeting—and budgets in general—across states to ensure consistency, comparability, and transparency in reporting, particularly for crucial sectors like healthcare.

Healthcare Schemes and Programs

This section will cover state government schemes and performance of the states in some central government schemes for women’s healthcare.

Central Government Schemes

Pradhan Mantri Matru Vandana Yojana (PMMVY)

Pradhan Mantri Matru Vandana Yojana is aimed to provide cash incentives as partial compensation for wage loss, enabling pregnant and lactating mothers to rest adequately before and after the birth of their first child, and to encourage a positive attitude toward the girl child by offering additional incentives for a second child, if it is a girl. In case of the first child, the mothers receive an amount of ₹5000 in two instalments and for the second child, the benefit of ₹6000 is provided subject to the second child being a girl. The PMMVY funds are shared between the central and state governments in a 60:40 ratio (MWCD, 2022). The centrally-sponsored scheme by the Ministry of Women and Child Development includes cash incentives for early pregnancy registration, cash transfers for nutrition assistance after six months of pregnancy, and cash transfers for birth registration.

For PMMVY, West Bengal spent 150 crore in the year 2022-23. However, between 2023-24 and 2024-25, West Bengal has allocated only one crore for implementation of this scheme. While almost 3 lakh women enrolled for this scheme in the year 2020-21, only 36 women were provided maternity benefits. The trend continued, until 2022-23, where more than 4.1 lakh women received the benefits of PMMVY out of the 5.3 lakh registered beneficiaries.

As per the gender budget documents, in case of Maharashtra, the state government spent 55 crores on PMMVY in the year 2018-19. The amount spent was the highest at 120 crores in 2019-20. Since then, till 2022-23, the amount spent fluctuated between 90 to100 crores. The implementation of PMMVY in Maharashtra has demonstrated consistent efforts in ensuring that a significant number of enrolled beneficiaries receive the scheme’s benefits. In 2020-21, 5.6 lakh beneficiaries were enrolled, of which 4.2 lakh (approx. 75%) successfully received the benefits. The trend continued positively in 2021-22, with 6.5 lakh beneficiaries enrolled and 4.6 lakh (around 72%) receiving benefits, reflecting impactful outreach and implementation mechanisms. Although the number of beneficiaries who received benefits decreased to 3.3 lakhs in 2022-23 from an enrolment of 5.8 lakh, Maharashtra’s performance remains better than many states (Open Government Data Platform, 2024).

Janani Suraksha Yojana (JSY)

Janani Suraksha Yojana, a scheme by Government of India under the National Health Mission, was implemented with the objective of reducing maternal and neonatal mortality by promoting institutional delivery among poor pregnant women. This scheme is fully funded by the Central Government. In the year 2020-21, West Bengal utilised 99%, whereas Maharashtra utilised 98% of its allocated funds. These numbers decreased in 2021-22, where West Bengal spent 78% and Maharashtra spent 86% of the allocated budget for the scheme. Between 2019-20 and 2020-21, institutional deliveries under JSY decreased by 1% in Maharashtra and 5% in West Bengal (Kapur et al).

Schemes in Maharashtra

Mazi Kanya Bhagyashree Yojana

The Mazi Kanya Bhagyashree Scheme is an initiative aimed at improving the status of the girl child through a multi-dimensional approach that includes financial security, education, and health interventions. Under its health component, the scheme seeks to ensure access to adequate healthcare services for girls, thereby addressing issues of malnutrition, anaemia, and other health challenges that affect young girls in Maharashtra. The scheme includes provisions for regular health check-ups, immunization drives, and awareness campaigns to educate families about the importance of healthcare for girls.

The expenditure pattern of Maharashtra under the Mazi Kanya Bhagyashree scheme reveals significant fluctuations over the years. In 2018-19, the state spent ₹10 crore on the scheme, which decreased to ₹8 crore in 2019-20 and further dropped to ₹5.5 crore in 2020-21. Notably, none of the ₹1 crore funds allocated were spent in 2021-22, indicating lack of prioritization during that year. However, the expenditure rebounded in 2022-23, reaching ₹12.7 crore, demonstrating renewed focus. The budget for 2023-24 has been set at ₹11.9 crore, with an ambitious increase to ₹17 crore for 2024-25 (Maharashtra Finance Department, 2024), reflecting the government’s intention to scale up its efforts. These shifts suggest variability in the scheme’s prioritization, potentially influenced by fiscal constraints, administrative challenges, or shifts in policy focus.

Lek Ladki Yojana

Launched by the Government of Maharashtra in October 2023, the Lek Ladki Yojana is designed to empower girls by addressing key challenges such as low birth rates, high mortality rates, malnutrition, and school dropouts, while also preventing child marriages. Under this scheme, an amount of ₹1,01,000 is provided in five stages to families holding yellow and orange ration cards after the birth of a girl child, reinforcing the focus on her health, education, and overall development. Under the scheme, expenditure of 7.79 crore was incurred on more than 15 thousand beneficiaries during 2023-24 (Maharashtra Economic Survey, 2024).

Maher Ghar Scheme

In Maharashtra, although schemes like JSY and PMMVY have been implemented, pregnant women in tribal areas continue to face significant barriers in accessing healthcare services (Raghuram, 2024, Mathrubhumi, 2024). Many tribal villages lack proper roads, and even where pucca roads exist, reliable transportation to health centres is often unavailable. These logistical challenges are a critical factor contributing to the high maternal and neonatal mortality rates in these areas (GIPE, 2024). As a solution to these issues, the Maharashtra government launched the Maher Ghar scheme in nine tribal districts – including Palghar, Nandurbar, Yavatmal and Gadchiroli – to improve maternal and child health outcomes. The scheme focuses on increasing institutional deliveries by providing better access to healthcare facilities in tribal and inaccessible areas, ultimately aiming to reduce maternal and child mortality rates. Through this targeted intervention, the government seeks to bridge the gap in healthcare access for the state’s tribal population (NRHM).

In 2018-19, the scheme benefited 2,649 women with an expenditure of ₹30 lakhs. This slightly declined in 2019-20, with 2,525 beneficiaries and a reduced expenditure of ₹20 lakhs. 2020-21 marked an increase, with ₹32 lakhs spent to support 2,739 beneficiaries. The numbers dropped again in 2021-22, with ₹24 lakhs spent and 2,203 women benefitting. By 2022-23, the number of beneficiaries further decreased to 1,788. This decline is attributed to lack of sensitisation and training among healthcare workers at the PHCs (Chakraborty, 2023). This trend highlights the need for consistent funding, improved awareness, and logistical support to ensure sustained impact.

Promotion of Menstrual Hygiene

The initiative to ensure access to high-quality sanitary napkins for adolescent girls in rural areas, along with promoting safe disposal methods, has experienced notable variations in expenditure and reach over the years. In 2019-20, ₹4 crore was spent, benefitting 10 lakh girls, indicating a significant outreach effort. This expanded dramatically in 2020-21, with ₹9 crore allocated to reach 36 lakh beneficiaries. However, a sharp decline was observed in subsequent years, with only 3 lakh beneficiaries in 2021-22 and just 24,000 in 2022-23, despite an expenditure of ₹5 crore that year. The program saw a resurgence in 2023-24, with ₹21 crore spent to benefit 24 lakh girls. These fluctuations underscore the need for consistent funding, effective implementation, and monitoring mechanisms to ensure sustainable and widespread access to menstrual hygiene products for adolescent girls in rural areas.

Schemes in West Bengal

West Bengal lacks dedicated schemes targeting women’s healthcare, particularly in the areas of menstrual and maternal health. This is notably surprising given the state’s long-standing governance under a woman Chief Minister. In the absence of such specific initiatives, this analysis will focus on examining the allocation of funds for women within the broader framework of general healthcare schemes in the state.

Swasthya Sathi Scheme

Swasthya Sathi scheme is a health cover for secondary and tertiary care up to ₹5 lakh per annum per family (WB Govt, 2016). From 2022-23 actuals to the current budget estimates, the state government has either spent or estimated an expenditure of around ₹1250 crores specifically for women for this scheme. Recently, the CM of the state opened a probe into the sudden surge in expenses under the Swasthya Sathi Scheme during the RG Kar protests (PTI, 2024).

AYUSH Suswasthya Kendra

The AYUSH Suswasthya Kendra initiative by the West Bengal government focuses on establishing Health and Wellness Centres across the state. In the fiscal year 2022-23, ₹7 crore was allocated specifically for women under this scheme. The allocation increased to ₹23.5 crore in 2023-24 and is projected to rise further to ₹41 crore in the 2024-25 budget estimates (WB Ministry of Finance, 2024).

Assistance for Cancer Treatment

Out of its budget for cancer treatment assistance, ₹45.2 were spent on women in the year 2022-23. The revised estimates for 2023-24 are ₹49.3 crore, whereas budgeted estimates for the year 2024-25 are ₹49.14 crores for women.

Health Indicators and Outcomes:

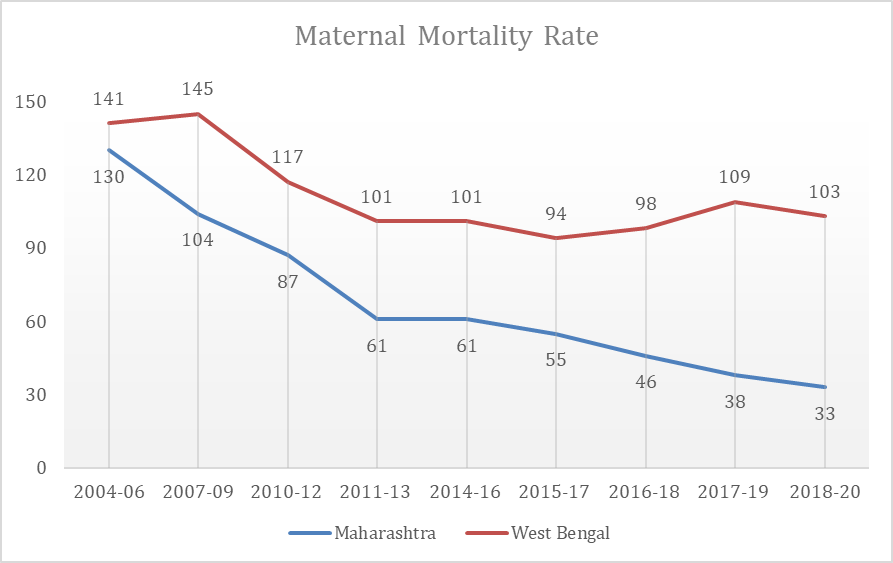

Maternal Mortality Rate

The data on Maternal Mortality Rates (MMR) reveals significant trends in Maharashtra and West Bengal over the years. Maharashtra consistently demonstrates a sharp and sustained decline in MMR, reducing it from 130 in 2004-06 to 33 in 2018-20 (MoSPI, 2023). This improvement highlights the state’s focus on maternal healthcare interventions, including increased institutional deliveries, enhanced access to healthcare facilities, and implementation of maternal health schemes like Janani Suraksha Yojana and Maher Ghar in tribal areas.

Source 7: Women and Men in India 2023 – Health

In contrast, West Bengal shows a less consistent trajectory, with MMR declining from 141 in 2004-06 to 101 in 2011-13, followed by an increase to 109 in 2017-19 before reducing slightly to 103 in 2018-20. The relatively slower and inconsistent progress could indicate gaps in maternal healthcare services or accessibility issues, particularly in rural or underserved regions. The stark difference in MMR trends between the two states underscores the need for West Bengal to strengthen its maternal health policies and infrastructure, drawing lessons from Maharashtra’s success.

Anaemia Prevalence

The prevalence of anaemia among women and adolescent girls in Maharashtra and West Bengal reveals significant disparities, with West Bengal consistently exhibiting much higher percentages compared to Maharashtra and the national average. In Maharashtra, anaemia among non-pregnant women (15-49) increased from 47.9% in NFHS-4 to 54.5% in NFHS-5, closely aligning with the national average of 57.2%. Similarly, the prevalence among pregnant women rose from 45.7% to 49.3%, remaining below the national average of 52.2%. Among adolescent girls (15-19), anaemia prevalence increased from 49.7% to 57.2%, still lower than the national figure of 59.1%. Despite the rising trend, Maharashtra’s figures remain relatively better, suggesting a more effective implementation of anaemia control measures compared to other regions.

| Prevalence of Anaemia (in %) | |||||

| Non-Pregnant Women (15-49) | Pregnant Women (15-49) | All Women (15-49) | Adolescent Girls (15-19) | ||

| India | NFHS – 5 | 57.2 | 52.2 | 57 | 59.1 |

| NFHS – 4 | 53.2 | 50.4 | 53.1 | 54.1 | |

| Maharashtra | NFHS – 5 | 54.5 | 45.7 | 54.2 | 57.2 |

| NFHS – 4 | 47.9 | 49.3 | 48 | 49.7 | |

| West Bengal | NFHS – 5 | 71.7 | 62.3 | 71.4 | 70.8 |

| NFHS – 4 | 62.8 | 53.6 | 62.5 | 62.2 | |

Source 8: Reply in Lok Sabha by MoS, MoHFW

In contrast, West Bengal’s anaemia rates are significantly higher and alarming. For non-pregnant women, prevalence surged from 62.8% in NFHS-4 to 71.7% in NFHS-5, far exceeding the national average of 57.2%. Similarly, for pregnant women, anaemia increased from 53.6% to 62.3%, and for adolescent girls, it reached a concerning 70.8%, well above the national average of 59.1%. These figures highlight critical gaps in addressing anaemia in the state, pointing to issues such as inadequate dietary diversity, limited healthcare access, and insufficient implementation of anaemia control programs. The stark difference between Maharashtra and West Bengal emphasizes the need for targeted and state-specific strategies, particularly in West Bengal, to combat anaemia and improve women’s and adolescents’ health outcomes.

Conclusion

The comparative analysis of women’s healthcare in Maharashtra and West Bengal reveals distinct strengths and challenges in the approaches adopted by the two states. Maharashtra has demonstrated consistent efforts in implementing women-centric healthcare schemes, such as PMMVY, Maher Ghar, and initiatives targeting menstrual health and cancer treatment. However, gaps remain, particularly in addressing the unique needs of tribal and rural women, where issues like accessibility to healthcare facilities, lack of reliable transportation, and poor infrastructure persist. While the state has made commendable progress in reducing maternal mortality and anaemia prevalence, the data underscores the need for sustained and targeted interventions, especially to bridge disparities in underserved areas.

In contrast, West Bengal’s approach to women’s healthcare has been less robust, with a noticeable absence of state-specific schemes focusing on maternal and menstrual health. Despite significant budgetary allocations for general healthcare schemes such as Swasthya Sathi and AYUSH Suswasthya Kendras, the lack of targeted interventions for women is a glaring oversight. The state also faces challenges such as a persistently high maternal mortality rate and alarming anaemia prevalence among women and adolescent girls. This highlights the need for West Bengal to design and implement women-specific health programs, improve healthcare infrastructure, and prioritize awareness and behavioural change campaigns.

An interesting observation in the comparison between Maharashtra and West Bengal is the allocation of their healthcare budgets. West Bengal consistently allocates a higher percentage of its budget to healthcare, including gender-specific health spending, than Maharashtra. However, a deeper analysis reveals that much of West Bengal’s gender-specific healthcare budget comprises administrative costs rather than direct schemes targeting women’s health needs. In contrast, Maharashtra, despite allocating a smaller share of overall budget, has developed several focused schemes for women, such as Maher Ghar for tribal maternal health, initiatives for menstrual hygiene, and programs targeting cancer treatment assistance for women. These efforts demonstrate a more targeted approach to addressing the specific health challenges faced by women.

The takeaway from this comparison is that higher budget allocations do not necessarily translate to better outcomes for women’s health unless the funds are directed toward impactful, scheme-based interventions. West Bengal needs to move beyond administrative expenditure and prioritise the development and implementation of women-focused healthcare programs to address pressing issues like maternal mortality and anaemia. On the other hand, Maharashtra should aim to increase its budgetary commitment to women’s healthcare, especially in underrepresented areas, to expand its reach and impact. For both states, aligning budgetary priorities with outcome-oriented strategies is essential for improving women’s health outcomes effectively.

In conclusion, both states must adopt a more comprehensive, women-centric approach to healthcare that addresses their unique socio-economic, geographical, and cultural contexts. Maharashtra can build on its existing framework by focusing on underserved regions and ensuring equitable access to healthcare services. West Bengal, on the other hand, needs to prioritize the development of dedicated women’s health programs and align its budgetary priorities accordingly. Both states must recognize that investing in women’s healthcare is not just a public health imperative but also a critical driver of social and economic development. Effective implementation, robust monitoring, and adequate resource allocation will be essential to achieving long-term improvements in women’s health outcomes in both Maharashtra and West Bengal.