Altruistic suicide is when someone sacrifices their life to save or benefit someone else’s. In India, particularly in Maharashtra’s agrarian-crisis impacted regions, news reports a worsening mental health crisis. This increases altruistic suicides rates among children. This commentary explores the depth of mental health challenges that farmer’s children face. The discussion highlights the role of socio-economic deprivation in altruistic suicide, concluding with the knowledge that there is a dire need for a holistic and inclusive mental health programme.

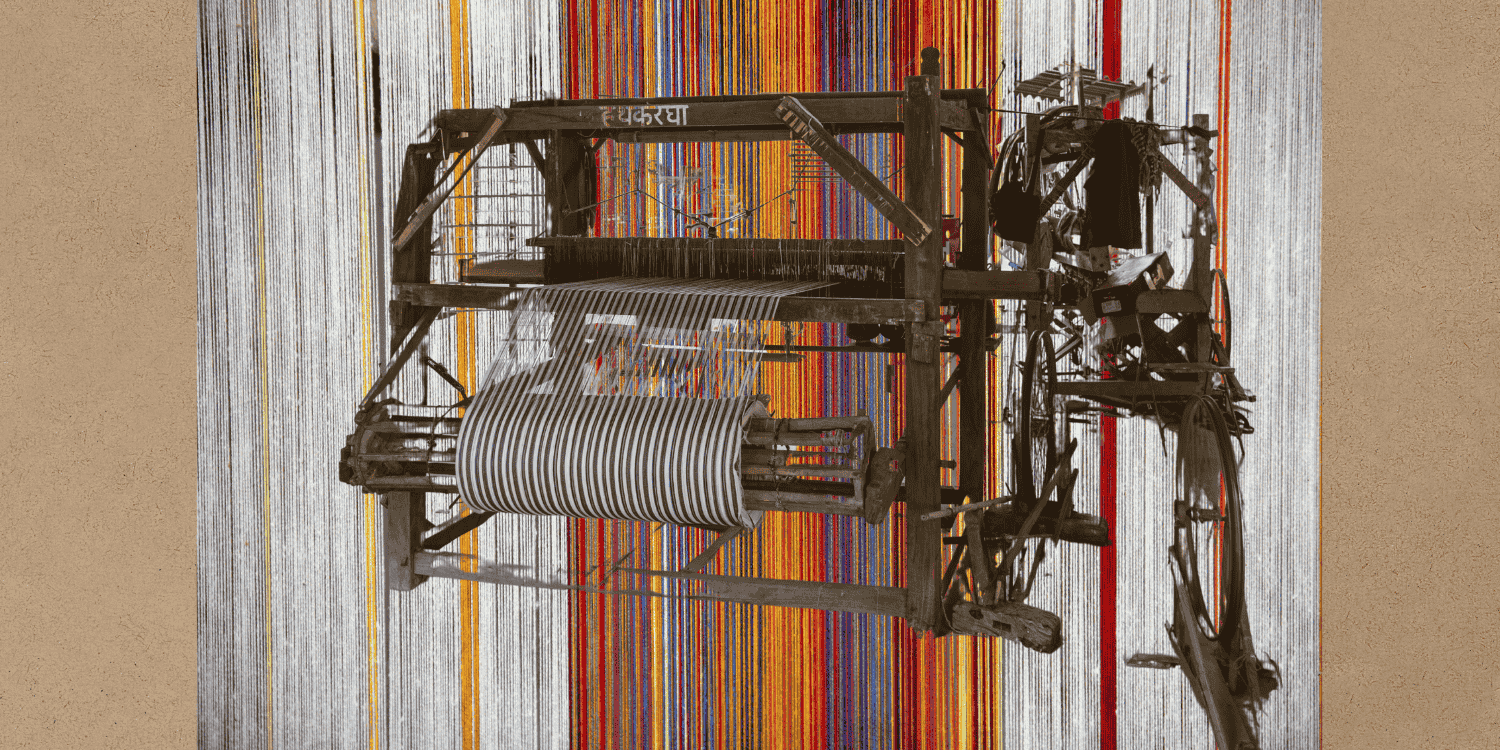

The Agrarian Crisis and Farmer Suicides in Maharashtra

The prevalence of farmer suicides in India has long served as a grim example of India’s worsening agrarian crisis. The rapid increase in input prices, global price shocks, and per capita household expenditure combined with a sharp decline in credit availability, rural wages, and agricultural investment has crushed farmers’ lives (Sainath 2010).

In 2019, India recorded a total of 1,39,123 suicides (National Crime Records Bureau [NCRB] 2020: 194), of which 7.4% were persons engaged in the farming sector. Bankruptcy or indebtedness (38.7%) and farming (19.5%) related issues accounted for about 60% of all suicides recorded (NCRB 2016: 265).

However, these figures are an underestimation of the actual number of farmer suicides. This is both a result of underreported cases due to social stigma and the change in NCRB data collection process, which now classifies agricultural labourers and farmers as separate categories (Sainath 2014).

Maharashtra, one of the richest states in India, accounted for 13.6% of the total suicides in 2019, the highest in the country (NCRB 2020: 197). Regions in central and eastern Maharashtra, including the Marathwada and Vidarbha, witnessed numerous suicide upsurges over the years. The highest number of suicides occurred among cash crop growers, specifically cotton farmers. Many such as Talule (2020) attribute these deaths to the increase in the cost of cultivation, the need for integrated pest management for the cotton crop, and rising seed and fertiliser prices. On average, for every rupee paid, farmers earn about 20 to 45 paise for most commodities (ibid).

With falling incomes and rising expenditures, the indebtedness has worsened. Factors such as the inability to pay dowry, healthcare expense burden amidst the pandemic, farming-related stressors, and addictions have added to farmers’ mental torment (NCRB 2016: 265). A study in the Yavatmal District in Maharashtra found that 55% of the surveyed farmers suffered from anxiety and 24.7% suffered from insomnia (Bomble and Lhungdim 2020: 3). Poor mental health is a crucial reason behind farmer suicides, which constructs a second tragedy of altruistic suicides among farmers’ children.

Child Mental Health Whilst High Farmer-Suicide Rates

Studies show that household income affects child mental health. Children from poorer households exhibit a higher degree of depression and anti-social behaviour (Kuruvilla and Jacob 2007: 276). In Maharashtra’s cotton-growing belt, families who lost the primary earning member suffer acute distress due to loss of income and a high debt burden. The traumatic experience of losing a household member, the family’s unpaid debt liability, and sudden new responsibilities to sustain the family severely impact children’s mental health.

After losing their parents, often the father, children find it challenging to return to their normal selves. Several news reports find that children stop communicating, eat less, sleep unusually more, and battle with visual or auditory memories of the event (Jyoti 2018). They lose any motivation to return to school, lose focus, and often complain of headaches and fevers. Some also develop post-traumatic stress disorder. These mental health challenges often go unattended, and the children do not receive the care they need.

Despite their declining mental well-being, children are forced to step into their parents’ shoes. Anecdotal evidence finds that older male children of the family find themselves shouldering several responsibilities such as repaying unpaid debt, funding the education of younger siblings, and facilitating the marriage of younger sisters. Usually, the only way to achieve this is to drop out of school, work in the fields to earn money and aid the other elder family members, typically mothers. Meanwhile, mothers tend to the agricultural duties, which the father used to perform, to sustain the family. Baccha kisans or child farmers are now common in Marathwada and Vidarbha regions (Hardikar 2009).