CONTEXT

An estimated 15.20 crore children were involved in child labour globally in 2016. Of this number, 8.8 crore were boys and 6.4 crore were girls. A staggering 48% of these children were 5 to 11 years old, while 12 to 14 and 15 to 17 age groups stood estimatedly at 28% and 24%, respectively International Labour Organisation 2017. Of the 15 crore children, 7.3 crore were involved in hazardous work, with 70.9% engaged in agriculture, 11.9% in industry and 17.2% in services (ibid). This paper attempts to outline the interlinkage of internal migration and child labour in India. It discusses the living conditions of accompanied and unaccompanied child migrants and why they often work under exploitative conditions. Meriting a brief discussion on the existing policy measures, the paper acknowledges the legal provisions and the loopholes, or the lack thereof, in addition to putting forth specific policy recommendations aimed at addressing child labour in the context of, and as an extension of, internal migration.

The census data sets from 2001 and 2011 mark a decrease in child workers. The 2001’s 1.27 crore fell to 1.01 crore in 2011 (Census 2001; Census 2011). However, rural India’s downward trend in child labour contrasted with an uptick in urban areas. Uttar Pradesh emerged as the state with the highest incidences of child labour with a staggering 21.8 lakhs, followed by Bihar’s 10.9, Rajasthan’s 8.5, Maharashtra’s 7.3, and Madhya Pradesh’s 7.0. Together, these five states constitute around 55% of the total working children in India (Census 2011).

Many of these child workers migrate within the country either as companions to their parents or independently, without a parent or a guardian. The former are called ‘accompanied children’, and the latter are referred to as ‘unaccompanied children’ in this paper. Some of them are sent to places across the country. Goa recorded the highest percentage of child migration with its 37.6%, followed by Arunachal Pradesh’s 19.6%, and Maharashtra’s 19.1% (Census 2011).

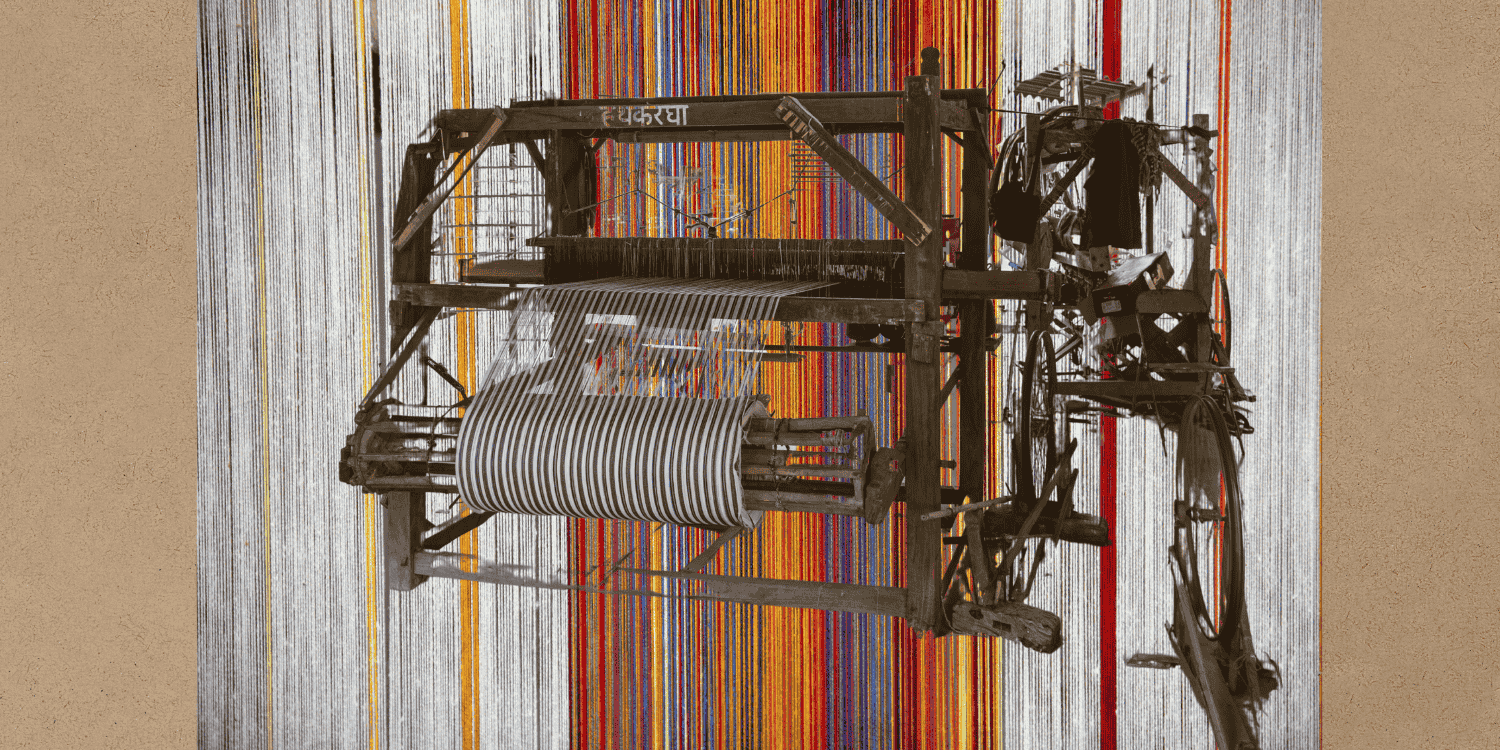

While the destination cities of these children are scattered across the country, these cities usually have high performing agriculture and construction sectors, agro-based industry, and a wide informal sector. Domestic employment, hotels, brick kilns, mining, quarrying, agriculture, export-oriented industries, fireworks, etc., are the major sectors employing child labour (International Labour Organisation 2013). Migrant children are more vulnerable to being engaged in work at very early ages compared to non-migrant children (Young Lives India 2020).

LIVING CONDITIONS OF CHILD MIGRANTS: A SNAPSHOT

Accompanied Children

Children who migrate internally are often accompanying their parents to destination regions and usually live in or near work sites. Living conditions at such migrant work sites are often deplorable. The workers and their families lack access to bare necessities such as nutrition, security, health, and education. For children of seasonal migrants, destination sites often lack necessary services, especially educational ones. This, combined with the schools’ seasonal admissions, makes migrant children particularly vulnerable to child labour (Van de Glind 2010). Social and cultural isolation, language barriers, extreme poverty, and frequent movement between two different social environments results in an inability to adjust to an arduous life for such children (Majumder 2011).

These locations are hazardous for children as they engage in coerced exploitative work. Migrant children are drawn into labour at ages as young as 6 to 7 and work as full-time labourers by 11 or 12 years of age (Smita 2008). Despite their full-time backbreaking work, child workers are paid half, or even less, than adult workers (Srinivasan and Gandotara 1993). Migrant workers, quite often, are paid less wages than local workers. These wages drop lower in the case of child workers. This incentivises employers to hire migrant labour instead of local workers, thereby contributing to child labour (Smita 2008).