Context

The year 2023 has been a milestone year for India, with the country assuming the G20 presidency for the first time while also being projected to become the most populous country in the world. However in 2023, India also enters its third year of a delayed population census. The 16th Indian Census, originally to be conducted in 2021, may be postponed to the second half of 2024 for a fourth time. The Covid-19 pandemic was cited as the reason for delay by the government.

It is of note that since the first Indian census of 1881, no other census has broken the decennial pattern until 2021. Even during wars or national disasters affecting census timeliness, as seen in 1941 due to the Second World War, the delays remained within the year, and the census was completed in the year it was planned for.

Furthermore, since the Covid waves of past years, especially the deadly second wave of early 2021, almost all of the pandemic limitations have been withdrawn. Even during the second wave, the government proceeded to hold assembly elections in 4 major states of Kerala, West Bengal, Tamil Nadu and Assam. All the elections involved extensive campaigning by major parties and high voter turnouts. The state of West Bengal requested the Election Commission, unsuccessfully, to conclude the last three phases of an eight-phase election due to the alarming number of Covid cases.

The census is a crucial exercise. It provides important data on the national population such as its trends in literacy, employment, poverty, and socio-cultural distribution among other factors critical to policy making. The absence of an updated census for the last decade coerced major policy decisions to rely on the old 2011 census data, using only projections to reflect the changes in national trends since then.

One of the predominant impacts of the delay is on the social welfare schemes of the country upon which the socio-economically vulnerable populations depend for their nutrition and well-being. Without a census, allocation of funds and other administrative requirements for social security schemes such as MGNREGA or the distribution of food through the Public Distribution System [PDS] has been made using population projections on old data from 2011.

In 2020 alone, an effective 10 crore people were left out of the PDS system due to ration cards being issued using old population figures. Other key government surveys also draw their sample from the census data, and in the absence of new data, the National Sample Survey and the National Family Health Survey [NFHS] have been using figures from 12 years ago. These are critical surveys, the results of which are used to make policy decisions and, most importantly, gauge an understanding of socio-economic progress.

Unreleased Data and Its Political Concerns

The 16th Census was controversial in that it set out to link the updated National Population Register [NPR] and the National Register for Citizens [NRC] with the census, for the first time. NPR was last updated in 2015, towards the end of 2019 and early 2020, the new NRC initiative became an issue of concern and scrutiny. The NRC exercise received major backlash from non-BJP ruled states as it was seen as a method to test Muslim citizenship. Thus, any attempts at discussing enumeration and data collection for the census came under suspicion, with the census itself taking on a political colour. As a result, the NRC exercise was withheld, with updates regarding the census taking a backseat.

Additionally, many states demanded a caste census, in order to determine the distribution of castes that do not fall under the Scheduled Caste and Scheduled Tribe [SC and ST] categories. Data on Other Backward Castes [OBCs] was collected during the 2011 census but has not been released. Many states believe a caste census is necessary to meaningfully address the structural caste-based biases in society. Presently, Bihar is conducting its own caste census, and stands to act as an example of the insights that may have been achieved with a national caste census.

The present understanding of caste distribution, of those besides SC/ST communities, is based on data from 1931 and continues to come under serious debate. Many governments since 1951 have explained how a caste census might negatively affect the social fabric of the country. The current government additionally claims that the collection of caste data for the 2021 census is cumbersome. However, the issue runs deeper. A caste census would shed light on the distribution of different caste communities, which once defined, has a potential to splinter and form new vote banks. This also raised concerns among religious communities, fearing that making caste distribution more visible would cause friction within the overall community. This would likely have political ramifications during election months, as the interests of more and newly defined communities would come forward. A caste census would also expose wealth and other disparities, which may result in new demands of affirmative action such as reservation. This would make it potentially more difficult for parties to target their electorates during campaigns, as more diverse, and perhaps conflicting, demands would need to be addressed.

The absence of the 16th census and the unreleased caste census data, unfortunately, are not the only example of missed and under-prioritised data. The Household Consumer Expenditure [HCE] Survey of 2017-18 was conducted, and then the results were simply discarded, citing discrepancies in the data. The discarding hints strongly at what the results could possibly have indicated, as leaked versions of the report showed a significant decline in consumption spending of the poor and an increase in poverty. It is of note, that this would be the first HCE survey after demonetisation in 2016, and would thus present a picture of the impact of the move on the financial well-being of households. While the government assured to conduct the HCE survey in 2020-2021, there has been no news regarding the same. As of 2023, there has been no new HCE survey.

The 2024 Census

Presently, the Home Minister has announced that the 16th census will be a digital census. Its enumeration will be conducted using tablets and mobile devices. States have been instructed to complete the House Listing and freeze administrative boundaries by 30th June 2023, indicating that data collection can begin by October 2023 (data collection is undertaken 3 months after the close of House Listing). However, according to the Home Minister, the digital platform for the same is not yet ready, and will likely be completed only in 2024.

Additionally, there is the option of citizens to “self-enumerate” by filling up their details on an online portal to save time and cover more data for the census. For self-enumeration [SE], one must have their details filled in the online NPR as well. The current SE portal, however, is still only in English, and a mobile friendly version of this portal is unavailable. Furthermore, the filling up of NPR online can be a digitally challenging task for a vast section of Indians as it involves navigating multiple web pages including a system of downloads and uploads through the process. Finally, reliance on digital self-enumeration has an unconscious urban bias. Since only those privileged enough to have the adequate technology, network, and knowhow would be able to successfully complete enumeration. The Post-Enumeration Survey of the 2011 census showed major gaps in data, with the gaps arising from rural and economically underserved areas. The potential for the same gaps remain for 2024.

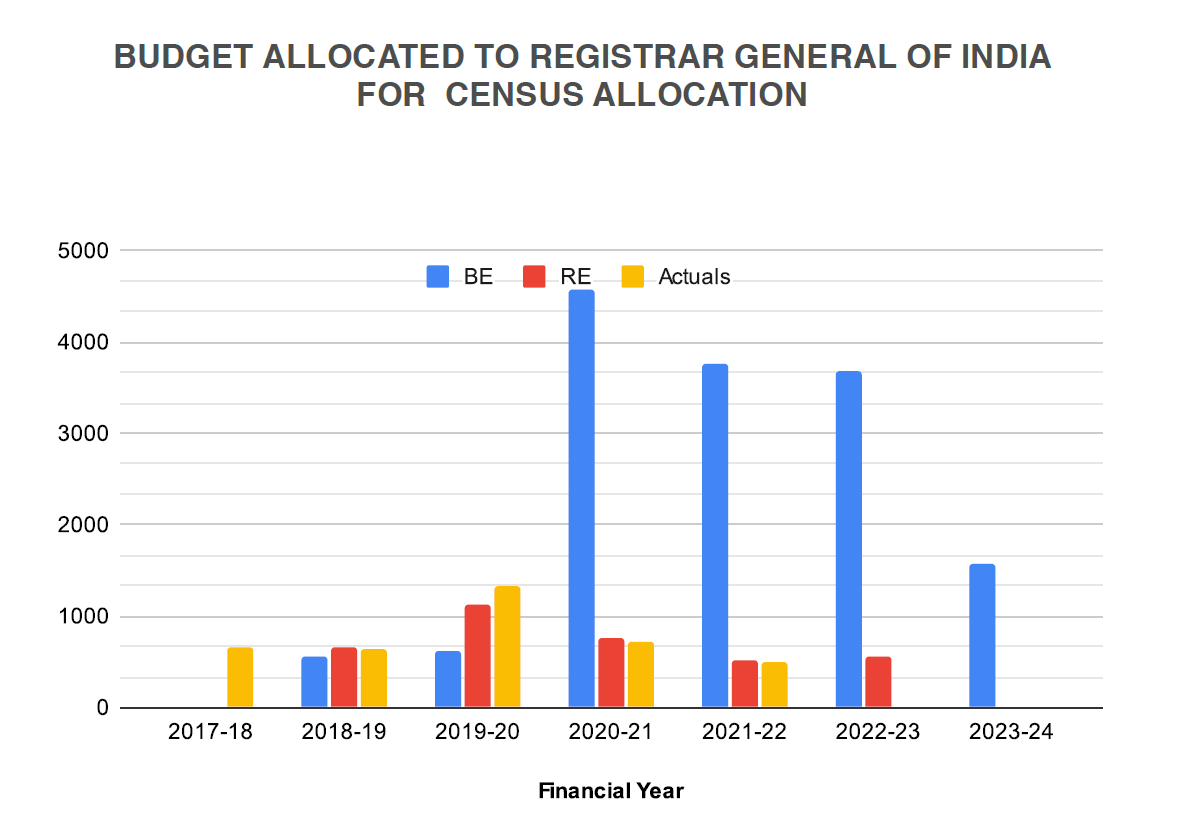

2024 will mark 4 years since the official delay of the census , and 5 years of delay in preparation and enumeration, if one counts from the year of data collection the 2021 census, i.e, 2020. The commitment to the census seems even more erratic if one were to look at the budget allocation for it. As shown in the chart below, every budget since 2020 has allocated a high initial estimate, only to have it revised to less than half. The differential between the budget and revised estimates [BE and RE] are indicative of planning for, and subsequent halting of implementation. Even in 2021, a major pandemic year, it appears that operations for a census were budgeted for, before being revised. This trend remained for 4 years, with the BE changing significantly for 2023-24. The budget estimate for it in 2023 stands at about Rs 1564 crore, less than half of the 2022 budget estimate, but three times the amount of the revised 2022 estimate

Budget Allocated to Registrar General of India for Census Allocation

Source: Compiled by the author using Union Budget documents using the Registrar General of India (RGI) budget allocations for 2019-20, 2020-21, 2021-22, 2022-23 and 2023-24. Only the actuals for 2017 are shown, and actuals and RE for 2022-23 and 2023-24 are not yet available.

Conclusion

Notably, the census stands out as a massive exercise of centre-state cooperation as it is the states that implement it. The census is also symbolic of an objective Indian federalism, where the insights are equally relevant and applicable for all states, regardless of political allegiance and competition. States collectively place their trust in the central government to plan and conduct the census every ten years.

While India, the world’s largest democracy, assumed the G20 Presidency in 2023, other key members of the G20 completed their census with minor delays, even amidst the pandemic. The United Kingdom and Russia completed their respective censuses in 2021 and the United States completed its first digital census in 2020. China, a key rival in South Asia and as populous as India, completed the census in 2020 itself. A non-G20 country, Pakistan, is set to complete their census in May 2023, while also being South Asia’s first digital census. Pakistan achieved this during heavy flooding across the country.

Key surveys, such as the National Sample Survey and the National Family Health Survey use population census details to determine the sample. The upcoming NFHS-6 for 2023- 2024 will be the first NFHS since the pandemic, and is likely to provide key insights on the socio-economic impact of the pandemic years on household well-being. Even for this NFHS, statistical modelling using the 2011 Census will be used to obtain the sample, as absolute population data will remain unavailable. For key schemes such as MGNREGA or the PDS system, the available funds to states and ration and job cards will remain contingent on 2011 Census data, until at least 2025.

In the first year of the Lok Sabha which will be formed in 2024, major deliberations regarding budgeting and social security schemes will use old data, with two more Union Budgets (2024-25, and 2025-26) being decided using outdated data. The true impact of policy making without updated population data will thus only come to light in late 2025, or early 2026. It is likely then, that corrections in policies will be required to account for major changes in India’s large population. Until then, projections will capture only a part of the image, even as key changes will remain invisible.